His Ghanaian biographer Kofi Ayim describes his story as “one of extraordinary resilience, courage, and enduring legacy.”

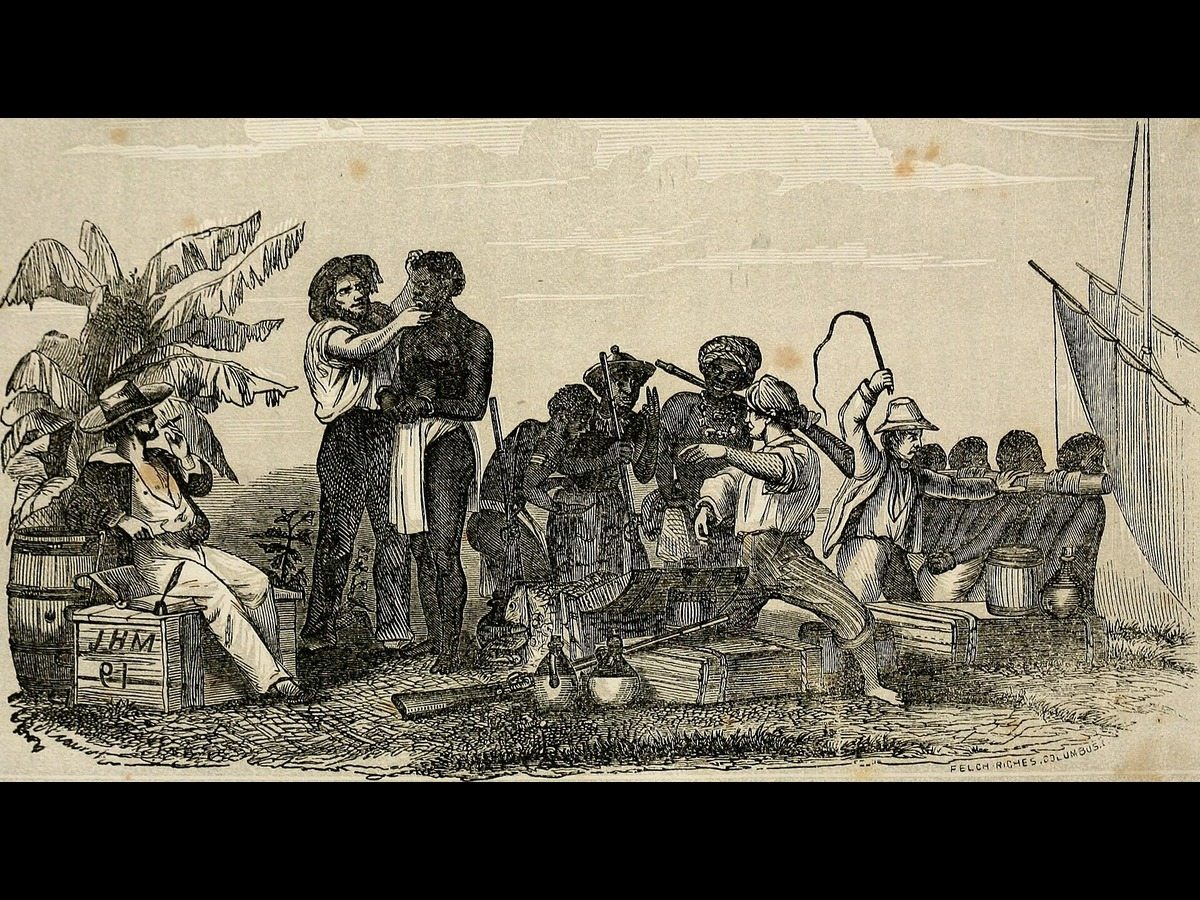

A product of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Jack Cudjoe or Cudjo Bakwante (sometimes spelled Banquante) is descended from royalty, and was sold from his native land, now known as Ghana, to become enslaved in New Jersey.

Born around 1723, it is not exactly known how Bakwante was enslaved, but historians like Ayim believe he was captured by a rival tribal group following a conflict before being sold to enslavers.

“Cudjo — if old enough in 1742 — could have been captured in a war between the Asante and Akyem, in which the latter was defeated,” Ayim said to NJ.com.

Becoming a victim of the transatlantic slave trade in the 18th century, Bakwante’s story is not lost in history, unlike his fellow African enslaved men and women whose stories have largely been buried.

Ghanaian author and biographer Ayim, in his book, “Jack Cudjo: Newark’s Revolutionary”, wrote that Bakwante later found himself in Newark, New Jersey but how he got there remains unknown. He became a slave of Benjamin Coe, one of the wealthiest people of Newark at the time. Coe did not force Bakwante to change his name; hence, he kept his name as Cudjo Banquante.

“Cudjo is an Akan name given to a boy born on Monday and can be used as a first or last name. Banquante (Baa Kwante) is a Ghanian name of royal heritage. I insisted on retaining my name, often passing on the information about my heritage to my family and all who would listen,” Bakwante’s biography states.

“I can tell you that I was able to adapt and survive the horrors of my transport and quickly became acclimated to my new home. Even my owner, Benjamin Coe IV, quickly saw my worth and I became one of the highly-valued, enslaved members of that family. My ability to make, build, and repair items earned me a respectable and trustworthy status in my new home.”

It was therefore not surprising that during the American Revolutionary War, Bakwante deputized for his enslaver on behalf of the patriots and became a soldier. In other words, he fought in place of his white enslaver.

Ayim writes that Bakwante “fought in the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777 outside Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Battle of Germantown on October 4, 1777, in Pennsylvania, the Battle of Monmouth, defended Elizabethtown Point in 1778, guarded Paulus Hook (present day Jersey City) in 1779, served in General Sullivan’s Expedition in 1779, and took part in the final and winning Battle of Yorktown in Virginia in 1781.”

For his service, Bakwante was granted his freedom, and Coe V, son of Benjamin Coe, purchased ten acres of land for him at the corner of Mercer and High (now Martin Luther King Boulevard) in 1791.

Bakwante built a home for his family on the land and started a horticultural business. He was said to be an exceptional gardener, who sold “fancy and exotic” plants and flowers to wealthy residents, according to the historian Charles Cummings. Other historians say he started his horticultural business way before New Jersey became the last Northern state to abolish slavery.

To recognize his knowledge of flowers and nature, the City of Newark held an Arts and Flowers Festival in his honor on June 10, 1995. This came years after his death and burial around 1823.

“My gifts to my family upon my death were land, a business, and, among my peers and the wealthy, a reputation for being an intelligent and talented man who was faithful to my family and to my God. I lived to be about 100 years old. My wife and I were fortunate enough to raise a large family that, for a good period of time, remained in Newark and in New Jersey. I was buried in Newark on March 5, 1823. I was funeralized and buried under the auspices of Trinity Church (Episcopalian) and Cemetery which was located where the New Jersey Performing Arts Center now stands. My descendants carried the name and stories of my success with them so future generations would know of their heritage,” his biography says.

Recently, The Daughters of the American Revolution, a group founded to help preserve Revolution history, dedicated a marker to him outside the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark. The Morristown chapter of the 135-year-old Washington, D.C.-based group erected the marker near Bakwante’s Newark burial place in a cemetery that once occupied the NJPAC site.

Barima Gyansi Korie, the traditional ruler, or chief, of the Kyebi-Ahwenease region, where Bakwante was born, was excited about the recognition.

“We are forever grateful and very appreciative of the efforts of the DAR to honor our dear Grandpa with a Marker and publication of his resiliency in life,” Korie told NJAM. “In fact, I represented the Asona Royal family and the Kingdom of Akyem Abuakwa on the Planning Committee of the Honoring Cudjo Banquante effort.”