When pianist and blues musician Daryl Davis entered the Silver Dollar Lounge in Frederick, Maryland, for a country gig one night in 1983, he was the only black man at the venue. Davis, who has jammed with big names like Jerry Lee Lewis, BB King and Chuck Berry, was unfazed by the situation and went ahead to deliver a splendid performance with his band.

It was his second time performing at the Silver Dollar Lounge, and it turned out to be a key moment in his life.

After his performance, he was approached by a man in the crowd who told him he’d never seen “a black man play piano like Jerry Lee Lewis.”

“I explained to this older white guy that Jerry Lee Lewis was influenced by the same black boogie-woogie and blues piano players as I was,” Davis recalled the moment recently.

“He didn’t believe me. Then I told him that Jerry Lewis is a good friend of mine and well, he didn’t believe that either, but he was fascinated.”

“So he asks me to join him for a drink,” Davis recounted. “I don’t drink so I had a glass of cranberry juice and then he took his glass and cheered me. Then he said, ‘You know, this is the first time I ever sat down and had a drink with a black person.’ I was instantly curious and thought, ‘What’s going on here?’ So I asked him why. He didn’t answer at first but eventually admitted that he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.”

Davis initially didn’t believe the man and started laughing until he produced his membership card. The two continued talking, and the white man even promised Davis that he would bring along his friends to the next gig. And that was how members of the Ku Klux Klan begun showing up in their numbers to watch Davis perform. In the process, he would talk with them.

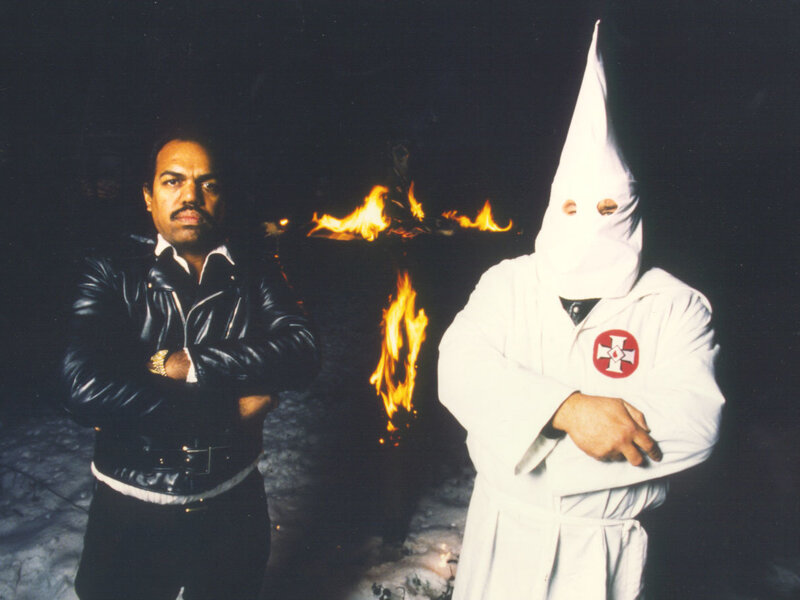

He then started befriending some members of the Klan, meeting them at their homes, and at their cross lighting rallies. During his long conversations with them, most of the Klansmen realized that “their hate may be misguided.” In the process, many of them left the Klan.

For the past 30 years that Davis began befriending members of the Klan, he has helped about 200 members leave the white supremacist group, including former neo-Nazi Jeff Schoep, who is now a good friend of Davis and travels with him to change white supremacists’ minds.

Throughout his years with the Ku Klux Klan, Davis became conversant with the tenets and hierarchy of the group, leading him to become the first black man to write a book about the white supremacist group entitled Klan-destine Relationships: A Black Man’s Odyssey in the Ku Klux Klan, which was published in 1998, according to the Guardian.

The Klan, in the 1970s, had a massive following. Members believed that they, as white people, were superior to blacks, Jews and other minorities.

In response to the rise of civil rights movements in the 1960S, the KKK killed civil rights workers, initiated the Greensboro massacre and launched firebomb attacks at school buses.

Many would, therefore, wonder why Davis would spend his free time away from music befriending Klansmen. His answer goes way back, even before his meeting with the Klansman at the Silver Dollar Lounge in 1983.

“In 1968, when I was the age of 10, I had a racist incident,” Davis recalled. “I was in the Cub Scouts and we were in a parade when people started throwing rocks and things at me. I didn’t understand why people would do that and I formed a question: ‘How can you hate me when you don’t even know me?’”

“The answer was always, ‘there’s some people who are just like that.’”

“Well, that wasn’t good enough for me. What does ‘just like that’ mean? Where does that come from? You’re not born ‘just like that. I was curious about racism ever since, but even still, nobody can seem to answer the question.”

“How can you hate me when you don’t even know me?” became the premise of his book. Before completing the book, he arranged a meeting with Robert Kelly, then the Grand Dragon of the KKK in Maryland, under the pretense that he wanted to include him in his book. Davis hid his race and so when the two first met, Kelly was shocked.

“He felt that he was superior to me, felt that black people had smaller brains than white people, that we’re prone to crime. We’re lazy … you name the stereotype. I heard them all,” Davis said in an interview with CBC Radio’s Edmonton AM.

But the two eventually became friends. “We continued the conversation for years,” Davis said. “He invited me to his home. He invited me to Klan rallies. And eventually, he gave it up as a result of our friendship.

“And today, his robe and hood are in my closet.”

Davis, despite threats and physical attacks, continues his meetings with Klansmen in a bid to challenge their beliefs.

“The best thing you do is you study up on the subject as much as you can. I went in armed, not with a weapon, but with knowledge,” Davis told NPR in 2017.

“I knew as much about the Klan, if not more than many of the Klan people that I interviewed. When they see that you know about their organization, their belief system, they respect you. Whether they like you or not, they respect the fact that you’ve done your homework. Just like any good salesman, you want a return visit and they recognized that I’d done my homework, which allowed me to come back again.

“That began to chip away at their ideology because when two enemies are talking, they’re not fighting. It’s when the talking ceases that the ground becomes fertile for violence.”

Even though Davis still performs sometimes, he has found that “lecturing and talking and educating people is far more important and necessary today.”