It has been 41 years since Enedina Alves Marques died of a heart attack. Alone in her apartment, located on Rua Emerlino Leão, in the center of Curitiba, South region of Brazil, she was found on the cold, tiled floor of the kitchen. At 68 years old, with poor health and a body worn out by the action of time, she ended her days swallowed up by the anonymity and invisibility to which thousands of human beings, especially women, are subjected.

The erasure of her deeds in life is little in contrast to the posthumous tributes, incapable of projecting her out of the labyrinth of neglect. But the tributes, it should be recognized, are healthy efforts in an attempt to inscribe the character’s history in the annals of national memory.

Enedina died in August 1981, during the harsh winter of Paraná. It was necessary to go down to the grave so that traces of her trajectory were recomposed and some graces popped up in the city she helped build. In the district of Cajuru, in Curitiba, a street was named after her. The Women’s Memorial, also in the capital of Paraná, gave her name among the 53 “notable” women – all of them Brazilian. Maringá, a neighboring city, was not left adrift and inaugurated the Enedina Alves Marques Black Women’s Institute, revering the character.

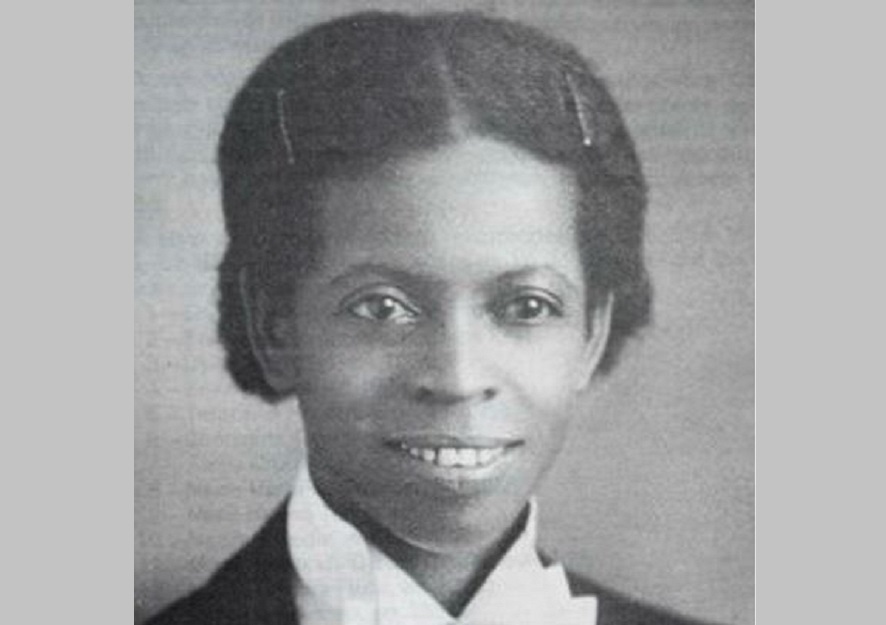

Now, dear reader, given the list of taxes, the question is: who was Enedina Alves Marques? What is her contribution to the history of Paraná, which awarded her in different public spaces and in private institutions?

Born on January 13, 1913, in Curitiba, Enedina was the daughter of black immigrants who arrived in the city in search of better living conditions. In a mostly rural Curitiba, marked by bossiness and rehearsing a process of urbanization, Enedina’s family, whose origin we don’t know, was added to the hundreds of Brazilians and European immigrants established in the region. Her mother, Virgília Alves Marques, provided for her offspring by working in family homes and washing clothes for those who hired her. Meanwhile, her father, Paulo Marques, provided small repair services to houses and farms to cover other family expenses.

Virgília and Paulo’s marriage succumbed to the wear and tear caused by the couple’s fights, something that pushed the matriarch, along with her children, to move to the house where Virgília worked. Now, in a cramped and poorly ventilated room, they lived on the property of Domingos Nascimento, an important republican intellectual from Paraná.

Enedina’s years in the new house were marked by housework, playing with the bosses’ children and sporadic reading during moments of rest. Access to the books that circulated in the house sparked the character’s interest in studies, who was literate at age 12 in a city where most of the inhabitants were illiterate. Her commitment to studying resulted in her diploma in primary education and, later on, in the conclusion of “complementary education”, which accredited her as a “normalist teacher”. Granted her new status, she began teaching at different schools in the interior of Paraná.

With the entry into the public service, Enedina replaced the broom with books and her services as a maid were temporarily interrupted. Now she dedicated herself to taking care of her own house, acquired with resources obtained from teaching, as well as from the literacy of students.

Enedina was tireless. She reconciled the many classes in regular schools with voluntary services provided to the underserved – children and adults. And here, “service” has an objective connotation: it means “to serve the other”, “to serve the human”. For this reason, she received people in her house, promoted literacy courses, assisted populations living in areas that were rarely visited, including by the local government, which was not very interested in meeting the basic demands of the unfortunate.

The meager salary of a teacher made it impossible for her to afford a university course in Civil Engineering, something she had dreamed of since training in teaching. In that period, mid-1930, there was a legislative determination to applicants for the Engineering course: they needed to undergo three-year professional training, disbursing their own resources, in a stage called “Complementary Course”. Only after the end of the journey, having ratified the “aptitude”, were they authorized to proceed to the University.

In order to facilitate higher education, she decided to combine classes at school with work at home with her family – the lack of resources, therefore, and the determination to graduate, made Enedina remember her years working as a maid. In the new venture, she chose the house of Iracena and Mathias Caron, a family from Curitiba with many possessions and with insertion in the highest hierarchical levels of nineteenth-century Curitiba. The family, even aware of the contractor’s skills, took advantage of both her skills in taking care of the house and her ease in dealing with letters and numbers. In this sense, they asked the teacher to teach their children to read between cleaning and other household care. A poor black woman, you see, writing to the rich children of a city that is still stained by racism.

The regular double shift of work (teacher and maid) made it possible for Enedina to pool resources, enter the complementary course and graduate from it – back in 1939. In the same year, she wrote an application addressed to the director of the Faculty of Engineering of Paraná ( FEP), requesting her registration in the qualification exams for graduation in Civil Engineering. The request was granted and the examination date was set.

After passing the exams, presenting the required documentation and paying for the registration fee, Enedina joined the Civil Engineering course as a freshman to train the elite of Paraná. She beat the odds to become the only woman in the class, the only black woman, the only worker of poor origin.

The journey in the Engineering course was full of shocks. There was a recurrent weariness between our character and the university bureaucracy — demanding documents within short deadlines and changing course schedules and deadlines, without informing the student. Furthermore, clashes between Enedina and her classmates were frequent, as well as her disagreement with prejudiced professors who suspected the intellectual capacity of a black woman in a hegemonically male, elitist and white course.

The Faculty of Engineering of Paraná mirrored the social order, marked by exclusion, the jettisoning of certain groups and racism rooted in everyday life. Dealing with all these elements in public spaces and in private institutions was a sine qua non for blacks in the southern city. The Civil Engineering course, for example, counted students from influential families in the city, with a consolidated academic trajectory and who did not need to work to pay for their studies – this framework, evidently, does not fit our biography.

Enedina Marques’ vicissitudes throughout her graduation course went beyond gender, ethnicity and social condition prejudices. In addition to them, she lived with repeated comments about her temperament, which they said were “explosive” and “disproportionate”, every time she took a position on a certain issue. Added to this, the student suffered from failing in some subjects, which delayed her graduation by 1 year – relevant data, considering the expensive tuition fee at a time when free higher education did not exist. Completing graduation, moreover, was a painful expedient, since the course had a high rate of failure and dropout – less than half of those enrolled made it to graduation.

The endless hours of study, diligent dedication and stubborn persistence, added to other particularities, led to Enedina’s graduation. On a sunny Saturday morning, December 16, 1945, while the perplexed country discussed the resignation of Getúlio Vargas, Enedina Alves Marques walked to Rua XV de Novembro, climbed the steps of Palácio Avenida, passed through the lobby of the building, greeted some guests and arrives at the majestic auditorium. A short time later, in a solemn and crowded session, the master of ceremonies announces the 33 graduates, 32 of them men. Emotional, trembling and with a racing heart, Enedina Alves Marques hears her name and gets up to seek her diploma. Watched by the murmuring crowd, she walks to the rostrum to pick up the straw and leave her fingerprints on Brazilian history.

Virgília Alves Marques, her mother, had died years before and was not present to applaud her, nor was her father, Paulo Marques, whose whereabouts we do not know. Perhaps some close friends and their siblings joyfully celebrated the memorable feat. That month, December 1945, the country would meet the first black woman who graduated in Engineering in Brazil and the first woman engineer in Paraná.

Shortly thereafter, Enedina began working at the State Secretariat for Traffic and Public Works. Professional respect in the works was won by the competence and quality of her work, but also by the revolver she wore at her waist – an artifact that discouraged the initiative of dozens of men who tried to trample on her due to gender and skin color.

The quality of her work led the governor himself, Moisés Lupion, to request her transfer to the Paraná Hydroelectric Plan, where she worked on the works to use water from the Capivari, Cachoeira and Iguaçu rivers. The Capivari-Cachoeira Plant, which in 1970 was named the Parigot de Souza Plant, still exists today and is located in the municipality of Antonina (PR). This project is among the most important in Enedina’s professional career. Other works also had her participation, such as Colégio Estadual do Paraná (CEP) and Fundação Casa do Estudante Universitário do Paraná (CEU), which still serves students from different Brazilian regions.

Her work as an engineer went hand in hand with Enedina’s engagement in organizations involved in women’s issues in Curitiba, among them the Soroptimist Society and the Centro Paranaense Mulheres de Cultura. These organizations carried out activities of different natures and put pressure on the government to build policies to overcome inequalities between men and women, especially in the state of Paraná.

In 1962, after long services rendered, Enedina retired and began to devote more time to volunteer services that she had never abandoned. In addition, she traveled to different regions of the world and got to know the reality of racial and gender discrimination that plague humanity. Would she have experienced in these places the same pitiful situations carried out in her native country? Would she have known the story of thousands of human beings supplanted by a patriarchal and racist structure? Would she have cataloged the deeds of other anonymous women who peremptorily contributed to their local realities? Unfortunately, we don’t know.

What we do know, however, is that the engineer spent the last days of her life walking the streets of Curitiba, talking to neighbors and friends, observing the movement of passersby, reflecting on the contradictions and changes in the city built by her efforts. Unknown to most of her fellow citizens, engulfed by invisibility, Enedina Alves Marques deserves to have part of her trajectory recomposed so that her achievements are recognized by ours and by the next generations.