Even though minorities served in the U.S. military since the Revolutionary War, they were usually not given the needed training and support compared to their white folks.

That was William Henry Johnson’s situation from the beginning. The Albany, New York native had enlisted in the all-black 15th New York National Guard Regiment, which was renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment when it shipped out to France.

The unit performed menial jobs as members were poorly trained but it was later lent to the French Fourth Army, which was experiencing a shortage of men.

With the French Army, Johnson would perform an act of heroism, earning him praise from then-President Theodore Roosevelt who eventually called him one of the “five bravest Americans” to serve in World War I.

What was this brave act? Johnson fought off scores of Germans single-handedly in the Forest of Argonne in 1918 during World War I.

Having joined the French Fourth Army, Johnson and his men who became the Harlem Hellfighters, were sent to the front lines in March 1918. They learned enough French words to be able to understand commands from superiors. They were given French rifles and helmets, even though they held on to the bolo knives used by the U.S. Army.

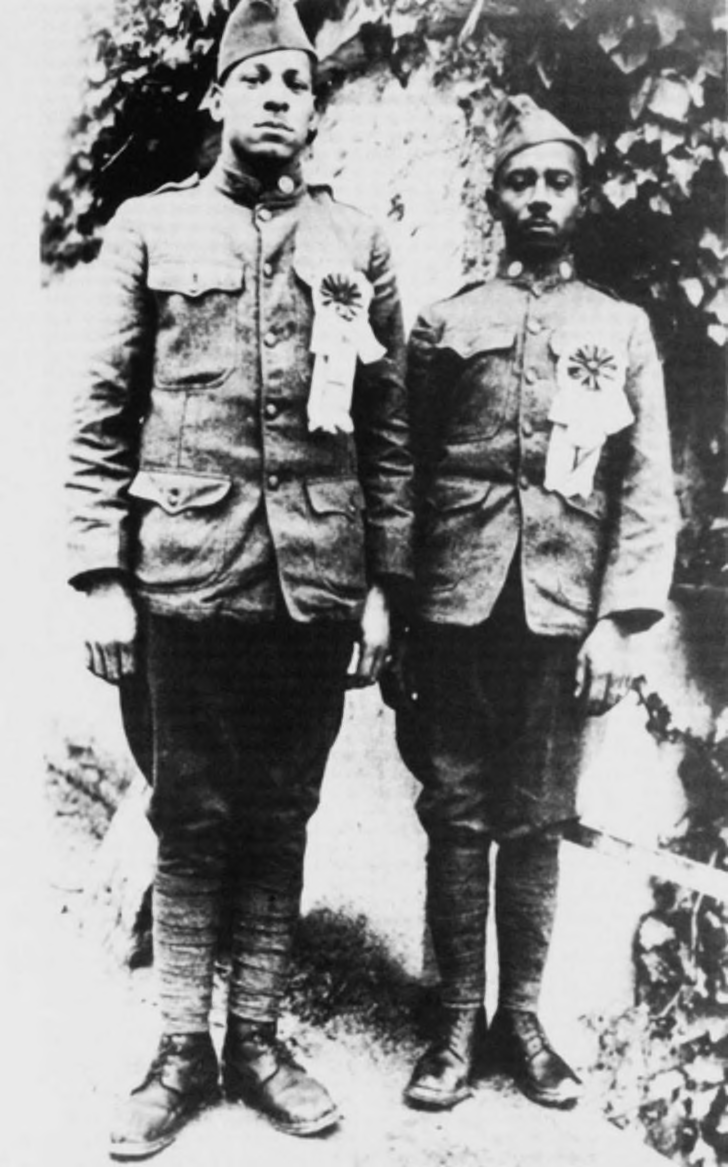

Alongside Needham Roberts, a man from Trenton, Johnson was assigned sentry duty on the western edge of the Forest of Argonne in 1918.

Johnson and Roberts were given the late shift; they were to patrol until midnight on the evening of May 14. They weren’t on duty long when the Germans started attacking them.

It first started with strange noises late into the night. Hearing these, Johnson urged Roberts, who was then tired and resting, to get up. But Roberts ignored, thinking his fellow soldier was just nervous.

Johnson, nevertheless, began “piling up his assortment of grenades and rifle cartridges within arm’s reach. If someone was coming, he would be ready,” writes Mental Floss.

Then he began to hear rustling noises, which ultimately became German soldiers who were rushing through the darkness. Realizing they were surrounded, Johnson urged Roberts to run and get help. This was around 2.am.

Roberts didn’t go far before he decided to return to help Johnson fight off the Germans, who had then begun firing at them.

Roberts was hit with a grenade in the process and got badly wounded to the extent that he couldn’t fight. Lying in the trench, Johnson handed him grenades, which he threw at the Germans.

But the German forces were too many, and they were advancing from every direction. Soon, Johnson ran out of grenades.

“He took German bullets in the head and lip but fired his rifle into the darkness. He took more bullets in his side, then his hand, but kept shooting until he shoved an American cartridge clip into his French rifle and it jammed,” an article on Smithsonian Magazine said.

“By now, the Germans were on top of him. Johnson swung his rifle like a club and kept them at bay until the stock of his rifle splintered; then he went down with a blow to his head. Overwhelmed, he saw that the Germans were trying to take Roberts prisoner. The only weapon Johnson had left was a bolo knife, so he climbed up from the ground and charged, hacking away at the Germans before they could get clean shot at him,” the article added.

Stabbing the German forces, including one in the ribs who had climbed on his back, Johnson was able to drag Roberts away from the Germans. After about an hour, the Germans retreated when they heard French and American forces advancing.

When reinforcements finally arrived, Johnson and Roberts were given medical attention. By day, officials found out Johnson had killed four Germans and wounded about 24 others.

Despite suffering 21 wounds, Johnson had prevented the Germans from breaking the French line.

“There wasn’t anything so fine about it,” he said later. “Just fought for my life. A rabbit would have done that.”

Having grabbed the unofficial label “the Black Death” and the official rank of sergeant, Johnson and his fellow soldiers prepared to return home to New York.

But before then, the French honored Johnson and Roberts with the Croix de Guerre, one of France’s highest awards for valor. They became the first two Americans to receive it. Johnson’s medal, however, included the coveted Gold Palm, for extraordinary valor.

In February 1919 when Johnson and the Harlem Hellfighters returned to New York, a parade to honor them was held at Fifth Avenue, with Johnson leading the procession in an open-top Cadillac while thousands celebrated them for their bravery.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/20111025011014henry_johnson-world-war-i-veteran.jpg)

But this bravery resulted in difficulties for most of them, especially Johnson.

He had returned from the war with bullets striking both feet, his thigh, his arm, and his head. A scar stretched over his lip, and he had to have a metal plate inserted into his left foot, according to Mental Floss.

These injuries prevented him from grabbing many employment opportunities and sources say his wife and three children subsequently left him.

Even after his death on July 1, 1929, it was unclear where his remains were until historians at the New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs found out in 2001 that he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

The following year, the New York native, who grew up doing many odd jobs before becoming a soldier, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. In 2015, then-President Barack Obama topped it with the award of the Medal of Honor.

What is more, every June 5, Albany celebrates Henry Johnson Day to acknowledge the day he enlisted while the city has an award under his name for people who make contributions to the area’s development.