When Nigeria capitalized on Africa’s rich biodiversity and knowledge of traditional medical healers and researchers alike to produce a sickle-cell drug in 1998, it was seen as a major breakthrough in medicine.

Research funding and output in Nigeria is not adequate, and the few discoveries from the country’s research centres hardly make it outside the labs, said Scitech Africa.

Therefore, the story of Niprisan, one of the first herbal medicinal products in Nigeria to have been successfully developed, patented and passed through clinical studies, was received with so much excitement.

The sickle-cell drug, produced by researchers from the country’s pharmaceutical research institute, the National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research and Development (NIPRD) and a traditional medicine practitioner was to provide relief for the millions of people affected with sickle cell at a lower cost base.

However, the locally developed drug would soon be caught up in a hullabaloo regarding its commercialization.

Sickle cell disease mainly affects people with African, Caribbean, or Middle Eastern ancestry. In the United States, mostly African Americans are affected, and worldwide, about 275,000 babies are born with it each year.

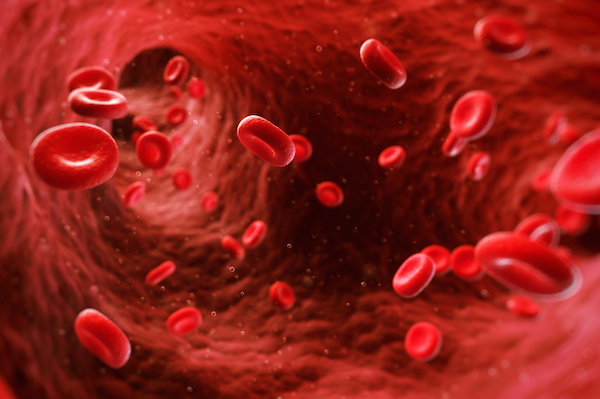

In sickle cell sufferers, normally round red blood cells, which carry oxygen around the body, are defective and shaped like a “sickle.” Those cells can sometimes lock together, clogging tiny blood vessels and causing bouts of extreme pain, organ damage, and even death.

According to the World Health Organisation, WHO, each year, about 300 000 infants are born with major sickle-cell disorders—including more than 200 000 cases in Africa. In Nigeria, about 150 000 children are born annually with the disorder.

Niprisan, which is a phytochemical formulated from parts of four different indigenous plants (Piper guineenses seeds, Pterocarpus osun stem, Eugenia caryophylum fruit and Sorghum bicolor leaves) is not a cure for Sickle cell anaemia.

It, however, manages the disorder, reducing the “crises” (the bouts of pain) without any serious adverse events on patients. The recipe for the drug was brought to the attention of NIPRD by a local reverend, Paul Ogunyale, in 1992. The Reverend, who also holds a master’s degree, claimed to be using the herbal medicine recipe to treat members of his congregation for sickle cell anaemia.

The herbal medicine has been used among the Yoruba people to manage the sickle-cell disease for many years.

The NIPRD liaised with Ogunyale for further development of his recipe into an effective medicine for the benefit of sickle-cell disease patients globally. When Niprisan was produced, there was only one approved sickle cell drug – Hydroxyurea.

Lab test shows that Niprisan works by reversing sickled red blood cells and protected them from being sickled when exposed to low oxygen tension. The drug was patented in the United States in September 1998 by NIPRID. It was patented first in Nigeria and later in the U.S. and 46 other countries. Seven NIPRD researchers and Ogunyale were credited as the inventors of the drug.

However, problems arose when it came to its commercialization. According to NCBI, finding a commercial partner in Nigeria to scale up and manufacture Niprisan was difficult.

“The local drug industry is not geared towards natural product manufacturing. They only produce imported generics. At the time, nobody had the facilities to produce Niprisan. As a result, I guess they [private sector] saw it as a very expensive investment with a lot of uncertainty…” said Dr. Inyang, the Director General of NIPRD.

Thus, exclusive rights to the patent were ultimately sold to a US-based, Indian-owned company, Xechem International, in 2003, a move that angered many Nigerians. Local scientists claimed that the sale of rights to the patent was illegal and against the national interest, but the government called their bluff, saying that the move would allow mass production of the drug.

The following year, Xechem managed to secure an “orphan drug” status for Niprisan in the United States in 2004 and in the European Union in 2005.

This qualified it for financial incentives to produce drugs considered unprofitable to develop, an article by Quartz explained. Xechem established a production plant in Nigeria and the drug was launched into the Nigerian market as Nicosan in 2006.

But in subsequent years, Xechem Nigeria failed to scale up its operations to its 50,000 capsules a day target. It was producing only about 10,000 and 15,000 capsules, making the drug scarce and expensive for locals at $25 per month supply. The situation was blamed on a series of mismanagement, litigation cases and corruption allegations faced by Xechem International and its Nigerian counterpart.

Several bank loans of millions of dollars could not even save the situation, forcing Xechem International to file for bankruptcy protection in the U.S. in November 2008. In March 2009, the exclusive license given to Xechem International for the manufacture and marketing of the drug was withdrawn after production slowed. The Nigerian government took over production through NIPRD, but that move couldn’t last long and in 2015, commercial production of the drug was stopped.

Two years later, the patent for the drug expired, meaning, Niprisan could be produced as a generic drug. Quartz reports that an Illinois pharmaceutical company, Xickle, already sells its own version of the drug, but it’s very expensive and therefore not affordable to many patients from poor areas in Africa.

However, last June, Nigeria made a new attempt that will ensure that the drug would be available in local pharmacies. Its NIPRD finally signed a production agreement with Nigerian pharmaceutical company May & Baker for commercialization of the drug.