Thomas Andrew Dorsey, the celebrated African-American musician who was known famously as “the father of Black gospel music” was born on this day in 1899. Dorsey, a composer, pianist, conductor and conductor of choirs, was a man believed to have used music as the language of his soul.

Dorsey is famously known for composing songs such as “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” and “Peace in the Valley”. He was so influential in the black gospel music field and due to his impact and unique style, many new compositions of songs were categorized as “dorseys” in his honour.

Thomas Dorsey’s leadership in Gospel music is believed to be responsible for the rise of the gospel sound and the legacy carried on by the present-day Gospel artists.

It would sound like a regular achievement but like many musicians who share stories of how they actually started singing from the church before settling down in secular music, Dorsey’s was a case in the reverse.

Dorsey was born in Villa Rica, GA on July 1, 1899, but was raised in the Atlanta area. His infantile years exposed him to the traditional Dr. Watts hymns as his father was a Baptist preacher and his mom a pianist in the church. He also got exposed to early blues and jazz – a genre of music he would soon become very active in.

Dorsey was interested in music as a young boy and hence, taught himself a wide range of instruments which he went on to play blues and ragtime while he was still in his teens. As a child prodigy, he became a very prolific composer, authoring witty, slightly racy blues songs like the underground hit, “It’s Tight Like That.”

In 1916, at the age of 17, Dorsey moved north to Chicago to pursue a musical career. There, Dorsey soon learned he couldn’t earn union scale wages as a musician without a card, and he couldn’t obtain the card without a formal music education because musicians’ wages were paid according to a scale determined by their credentials with the professional Chicago union of musicians.

To pay for his education, Dorsey worked days at a steel mill in Gary, Indiana, taking evening lessons at school. He soon established his own nightly rent-party circuit. By 1918, Dorsey had settled in Chicago and within months of his arrival, he began playing with area jazz bands including the Les Hite’s Whispering Serenaders and a jazz orchestra.

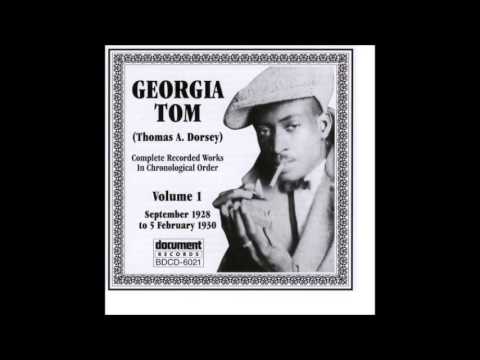

In 1919, Dorsey completed his musical studies at the Chicago College of Composition and Arrangement and obtained his union card. Now, performing under the name Georgia Tom, he was free to play anywhere in Chicago.

Building on his experience and influence from such groups, Dorsey formed a group of his own known as the Wildcats Jazz Band which traveled in support of Ma Rainey, one of the earliest African-American professional blues singers and one of the first generation of blues singers to ever record.

By 1928, Dorsey suffered a second nervous breakdown in many years which pushed him to opt for early retirement from the music business. However, a two-year recovery period would allow him to rethink this decision. During the period, a minister gave Dorsey enough convincing reasons to return to music. This time, though, this minister encouraged Dorsey to move from singing Blues to church music – Gospel.

Dorsey was equally convinced this was something he could attempt and so he made a first attempt at writing a gospel song in 1921. That song, “If I Don’t Get There,” met some success and that convicted him the more that this was a good step he was taking. He then did what was necessary: he renounced his dedication to secular music and embraced his new found love in gospel music.

Dorsey returned with a renewed sense of purpose devoting all of his talents to the church circuit. It was a truly challenging time in his life because, upon that major switch between genres, he began losing all the major blues jobs with little or no gospel offers forthcoming. He soon had to resort to peddling song sheets to make a living.

Persevering and looking for a big break, Dorsey’s luck took on an upswing by 1932. In that year, he successfully organized one of the first gospel choirs at Chicago’s Pilgrim Baptist Church from which his pianist, Roberta Martin, would in a few years emerge among the top talents on the church circuit. In that same year, he also founded the first publishing house devoted exclusively to selling music by Black Gospel composers.

Dorsey’s life seemed to be gradually taking on a good turn until a tragedy of tragedies struck: on a trip to organize a choir in St. Louis, Dorsey received the shocking and devastating news of the passing of his wife while she was giving birth to their son. This son too, two days later, would die.

Awe-struck and devastated, he locked himself inside his music room for three straight days emerging with a completed draft of “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” a song whose popularity in the gospel community is rivaled perhaps only by “Amazing Grace.” Setting his loss behind him, he enjoyed his most prolific period in the years that followed by authoring dozens of songs with a distinctively optimistic sensibility for audiences held in the grip of the Depression.

Initially, mainstream churches did not accept his Gospel music because of its apparent secular influence. The religious music that Dorsey proposed, called for a drastic departure from the music practices of the large protestant Black churches of Chicago. In spite of this rejection, the growth of the churches that played Dorsey’s music convinced the others to incorporate them into their churches.

Dorsey became a force to reckon with in the music industry. Soon, he became responsible for the bold innovation of a new musical style into the American church which completely changed the face of worship as we know it today.

Dorsey was also the first to write and publish a gospel song, going on to do Gospel music for over 60 years. Dorsey’s works have proliferated beyond performance into the hymnals of virtually all American churches and of English-speaking churches worldwide. In 1982, Dorsey was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame.