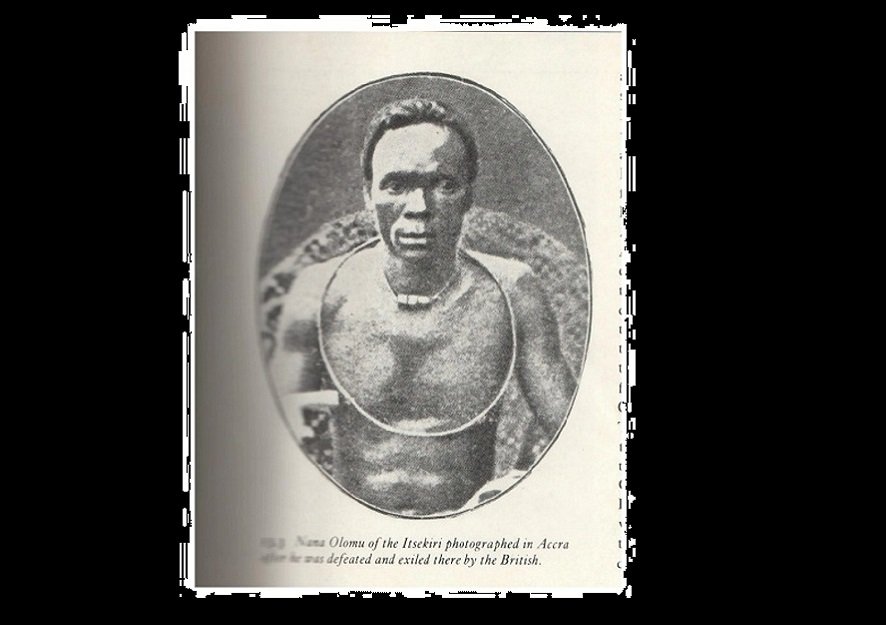

Nana Olomu made millions in the nineteenth century, becoming one of the greatest Africans to have ever achieved such a feat in his time but it is how influential he was in ensuring that he fought against the oppression from the British that makes his story even more historic.

Nana Olomu had little education but with determination, hard work, and a great mind for curiosity and the well-being of his people, he inherited wealth and multiplied it. Through that, he became one of Nigeria’s most influential figures, helping to save his people from their costly ignorance.

Born in 1852 at Jakpa in the Itsekiri region, Nana Olomu grew up to become a notable Itsekiri chief, a palm oil super magnate, and a fighter from the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria. As an Itsekiri, he became the fourth to hold the position of Governor of Benin River.

As a powerful nineteenth-century indigenous entrepreneur and great millionaire, Nana lived in a creek near the mouth of the Benin River, with Oba Ovonramwen of Benin (another powerful and influential figure) as two powerful Africans who successfully prevented European penetration of the hinterland of the Benin and its nearby rivers.

Nana inherited most of his wealth but he managed to expand his business through his shrewd business acumen by monopolizing trade. As a reflection of the grandeur of his achievements, Nana built a magnificent edifice at the turn of the century.

This edifice housed his personal effects and evidence of his contact with the Queen, administrators and traders of the British Empire. Many European merchants, missionaries, explorers and Consular Officers who visited the Benin River in the second half of the last century, and had occasion to meet Chief Nana, had nothing but great admiration for his outstanding personality, intelligence, wealth and hospitality.

His ability to speak the Urhobo language coupled with his liberality won for him the favour of practically all Urhobo traders on the River.

From having engaged with the Europeans for long, Nana Olomu got to learn and understand a thing or two about their language. This helped him interpret documents that sort to enslave his people.

For instance, during the era of treaty signing in Nigeria, Nana Olomu fully understood the immediate import of British imperial intentions in the Niger Delta. He was able to strike out offensive clauses which stipulated free access to British traders to trade wherever they pleased in his kingdom. These uncooperative tendencies on his part were the precursor to the Ebrohimi expedition of 1894.

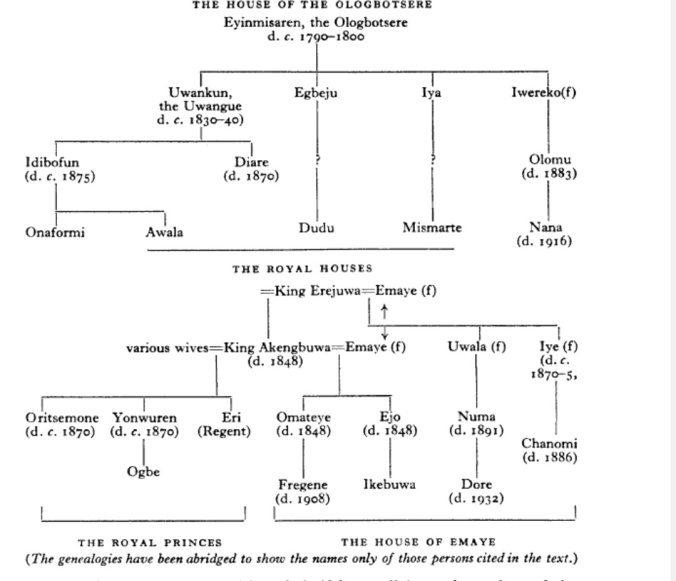

Nana Olomu was the last of a series of governors, starting with the installation of Chief Idiare in 1851 by John Beecroft, who was appointed in 1849 by the British Government as Consul for the Bights of Benin and Biafra.

Chief Idiare, along with Idibofun, Olomu (Nana’s father), and a host of other elders subsequently signed a treaty with Beecroft to protect trade in the area. Nana succeeded his father, Olomu of Ologbotsere, as governor.

Numa of Batere Emaye family – the family that was expected to succeed Olomu, decided to avenge the disgrace that had been brought on their family. Dogho (Dore Numa), an imperialist stooge and a son of the Emaye family, rose and provided valuable help that the British needed to defeat Nana.

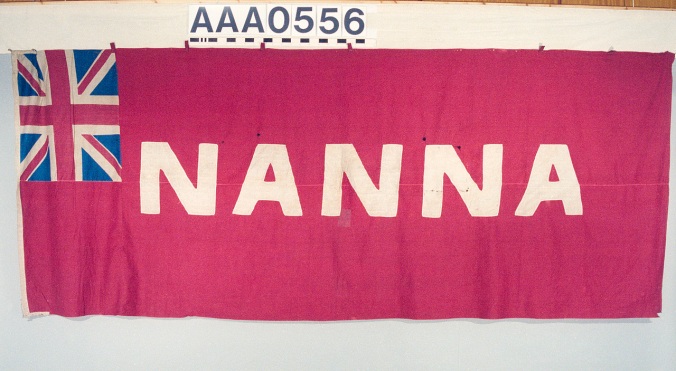

There is a historical fact that Nana wielded enough force to bring to submission anyone who was so unreasonably stubborn as to interfere with his trade anywhere; even the colonial masters. For many years, he concentrated his commercial activities on the Urhobo oil markets until he practically established a perfect monopoly over all the oil markets.

He was credited with having a fleet of 200 trade canoes and another 100 war canoes with the ability to muster 20,000 war boys. In fact, after his defeat in 1884, the arms seized in Ebrohimi included 106 cannons, 445 blunderbusses, 640 guns, 10 revolvers, in addition to 1640 kegs of gunpowder and 2500 rounds of machine gun ammunition.

With such an impressive military machine, enormous wealth and great influence were critical factors in his virtual monopoly of the palm oil trade.

Major Claude Macdonald, the British Commissioner and Consul General for Oil Rivers Protectorate in 1887 who once reported that Nana was “a man possessed of great power and wealth, astute, energetic and intelligent”, wrongly accused him of: disrupting commercial activities in the Niger Delta, of terrorizing the Urhobo and turning them against the British, of engaging in the inhuman traffic in slaves, and the most blatant lie, of practising human sacrifice.

It would, however, be revealed that Nana’s real offence was that his wealth, position and power gave him considerable influence over the areas surrounding the Benin River and the Warri district, thereby making the penetration of British traders to be extremely difficult if not impossible.

Accusations began to fly around on the personality of Nana because of his obvious influence and by the end of 1893, the Vice Consuls at Benin River had started to accuse the chief of gross disloyalty to the government. He did this mostly through his trading boys.

These accusations appeared to reach a climax, when in July 1894, his boys seized fifteen Urhobo people (including a local chief’s wife), for an alleged debt of 200 puncheons of palm-oil.

It was when Chief Nana refused to surrender those captives, blockading the River instead, that the government was obliged to use force to overthrow him towards the end of 1894.

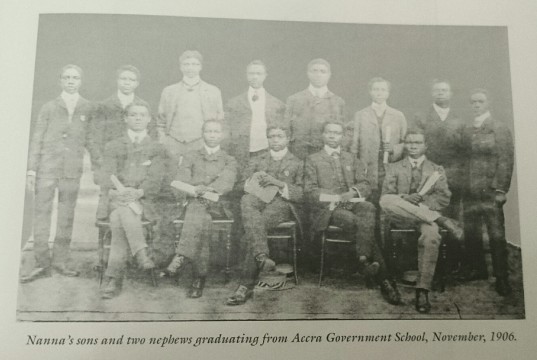

Nana was, therefore, captured after cessation of his war with the British and was exiled in Gold Coast (Ghana).

In Britain, in 1899, the Aborigines’ Right Protection Society led by some Gold Coast (Ghanaian) ethnic Fante intelligentsia with people like billionaire founder and president Jacob Wilson Sey, J E Casely-Hayford, George Hughes and others complained to the Foreign Office about “the arbitrary treatment” to which the chief had been subjected, the government’s failure to carry out “the searching investigation of his case which he had always sought”, and appealed for him to be given liberty to conduct his commercial affairs freely even if, for political reasons, he could not be restored to his old position.

A letter from Olomu was also enclosed containing his complaint that the maintenance was inadequate for him to support himself and five other persons. In his reply, the then Prime Minister, the Marquis of Salisbury, promised to look into the conditions of the chief’s maintenance but ruled out the possibility of a return to his homeland.

A month later, the question of his treatment was raised in parliament and the government again stated it would be unsafe to allow his return.

In 1891, the British tried to undermine Nana’s economic interests by opening up another Vice-Consulate at Sapele, apart from the one on the Benin River in order to penetrate the hinterland and reduce the trade on the Benin River – the main source of his wealth.

However, Nana retaliated by sending his agents to Sapele too. The British were astounded to find out that his agents were in firm control of the trade, and that his trading influence was extremely strong.

Indeed, he was so powerful and sufficiently wealthy to dictate his own trade terms, to hold up trade when it suited his fancy and to refuse to take trust from European firms.

Nana was reported to have stopped all trade in 1886 and 1892 to force English merchants to pay higher prices. Opposition to Nana grew not only from the merchants but also from those Itsekiri traders, including Dore Numa, who had suffered from Nana’s monopoly.

Consequently, in 1894, the British laid siege on Ebrohimi. Nana replied by further fortifying his capital. Henceforth, the resistance put up by him was bitter and daring, and as skilful as it was brilliant.

With the combination of conventional and guerilla warfare tactics, Nana used to the fullest advantage, his superior knowledge of the creeks along the British, to sail to Ebrohimi, thereby making what they initially thought would be a casual military expedition, one of their most difficult and costly imperial adventures in West Africa.

The British were forced to build up a large naval and military force off the Benin River, representing virtually the entire British naval strength in West Africa, and the most impressive collection of British forces in the Niger Delta up until that date. This action prompted the British to send four warships: the HMS Alecto, HMS Phoebe, HMS Philomel and HMS Widgem to attack all the villages around Ebrohimi, which were destroyed.

Yet, Nana refused to surrender or obey British entreaties to come for a discussion at the Consulate, based on the memory of what happened to Jaja when he acquiesced to such a request. And thus, all attempts to take Ebrohimi by going up the creek failed, and in fact, Nana successfully repelled the British forces on three occasions so they were forced to withdraw with ‘heavy’ casualties.

It must be noted that in about 2 ½ years before Chief Nana’s fall, the Urhobo Chiefs of Abraka, northeast of the Benin Consular district had concluded a Treaty of Protection with Her Britannic Majesty’s Government placing themselves and their people under British protection.

In the south and the south-east of the Urhobo country under Warri district not less than 14 such Treaties had also been entered into. The Treaty making activities were, however, intensified after the fall of Chief Nana.

Source: Reference: Rotimi K and Ogen O (2008). “Jaja and Nana in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria: Proto-Nationalists or Emergent Capitalists,” The Journal of Pan African Studies, 2008 vol.2, no.7.