Legendary civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., until he was fatally shot in April 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, was a preacher who used the tactics of nonviolence and civil disobedience to fight for equality and justice. Born on January 15, 1929, his known roles in social activism led to his death, and decades after, he continues to inspire many.

In fact, all the states in the U.S. annually observe the third Monday of January as Martin Luther King Jr. Day. As the nation celebrates King, it is also ideal to look at the women who created a platform to help the famed civil rights leader to succeed. Marcia Chatelain, associate professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University, believes that “there would be no King holiday, no civil rights movement, no opportunity to be reflective of how far we’ve come if it wasn’t for scores of women.”

“Women were significant in his life, their intellectual production, their spiritual accompaniment. … Women surrounded him in so many ways,” the Rev. Naomi Washington-Leapheart, a professor of theology and religious studies at Villanova University, also said in an interview.

These women inspired him, strategized with him, led civil rights protests and demonstrations, and ultimately became the backbone of the civil rights movement. Here are eight of such great women who significantly impacted King’s life and his work:

Coretta Scott King

She is known for being the wife of Martin Luther King Jr., but Coretta Scott King was an author, activist and civil rights leader in her own right. She got involved in politics as a student at Antioch College where she faced discrimination. While at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, she met MLK Jr., whom she married in 1953. They moved to Alabama, where they found themselves in the Montgomery bus boycott, two years later which cemented the couple’s involvement in the civil rights movement.

Just before the boycott, the Kings’ Montgomery house was bombed while Scott King was home alone with their child. They both survived and Scott King’s father and father-in-law pleaded with her to leave Montgomery but she refused, saying that she was not only married to King but married to the movement as well. King later said that if she had left Montgomery, he would have followed her and there may have never been a Montgomery bus boycott.

“My wife was always stronger than I was through the struggle. While she had certain natural fears and anxieties concerning my welfare, she never allowed them to hamper my active participation in the movement,” King said in The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. “In the darkest moments, she always brought the light of hope. I am convinced that if I had not had a wife with the fortitude, strength, and calmness of Corrie, I could not have withstood the ordeals and tensions surrounding the movement.”

Alberta King

Alberta King, described as a very soft-spoken woman, was said to be the pillar of the famous King family. She is mostly remembered for raising the most famous civil rights leader in history than her own activism. Before her assassination in 1974, Alberta King was a prominent figure at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, the church that helped shape her son. She also played active roles in the NAACP and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Her son, King, described her as one who never left his side throughout his civil rights campaign. “…behind the scene, setting forth those motherly cares, the lack of which leaves a missing link in life,” King wrote in one of his essays.

“In spite of her relatively comfortable circumstances, my mother never complacently adjusted herself to the system of segregation. She instilled a sense of self-respect in all of her children from the very beginning,” King wrote.

Dorothy Cotton

Dorothy Cotton’s life as an activist began at Gillfield Baptist Church in Petersburg where civil rights activist Rev. Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker was the pastor. Walker was also the leader of the Petersburg branch of the NAACP. Cotton became his secretary and organized protests to desegregate a public library and the whites-only lunch counter at Woolworth’s in 1959. The following year, she met King for the first time when he spoke at Walker’s church. King subsequently asked Walker to join him in Atlanta as the new executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). He agreed, and Cotton went along with her employer Walker to Atlanta.

Cotton would soon become the only woman in King’s inner circle. She was also the highest-ranking woman in King’s SCLC, typed King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, traveled with him when he went to Oslo to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, and was with him in Memphis hours before his assassination on April 4, 1968.

Cotton was so close to King that Pulitzer Prize-winning King biographer David Garrow recently described her as King’s “constant paramour” and “the most important woman in King’s life.” Many historians have also described Cotton as King’s “other wife”.

Jo Ann Robinson

Robinson was a successful educator and famous civil rights activist who has also been described as the real architect of the Montgomery bus boycott. In 1949, a bus driver attacked her for sitting in the bus’ “whites only” section. And so when she later became president of the Women’s Political Council in Montgomery, she started working towards desegregating the city’s buses.

When Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a White passenger in 1955, Robinson spent the entire night printing out 35,000 handbills calling for a boycott of the Montgomery bus system, according to BlackPast.

“Apparently indefatigable, she, perhaps more than any other person, was active on every level of the protest,” King wrote, according to the King Institute at Stanford University. Robinson died in Los Angeles, California in 1992.

Prathia Hall

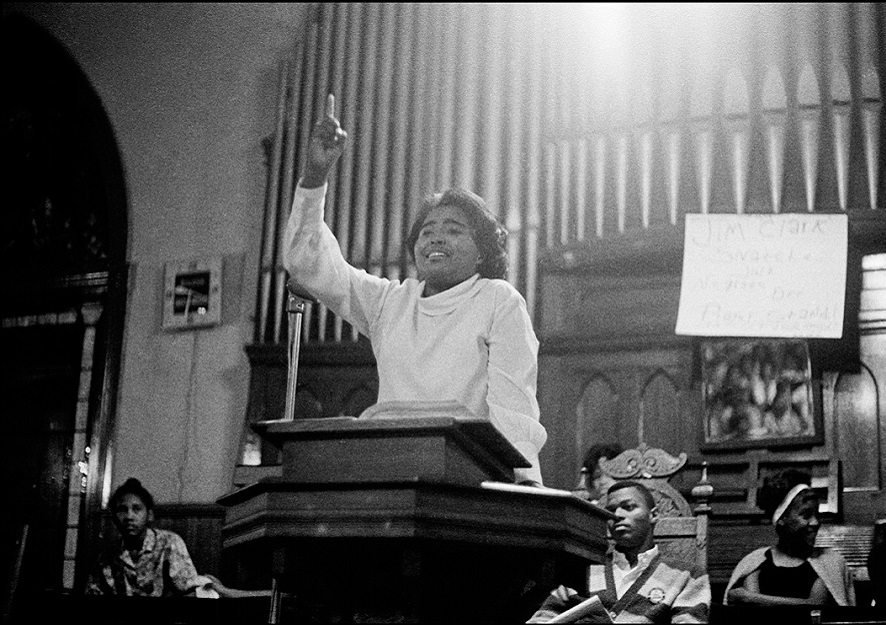

In September 1962, King visited Terrell County, Georgia to speak at Mt. Olive Baptist Church, which had been burned down by the Ku Klux Klan. At a vigil held at where the church once stood, Prathia Hall, a young college student, who was a member of the SNCC and the daughter of a Baptist minister, was invited to pray.

While leading the group of about 50 African Americans in prayer, Hall, known for her oratory skills, repeated the phrase “I Have A Dream,” and concluded by calling for racial justice. King was moved with Hall’s prayer, particularly, her use of the phrase, “I Have A Dream”. Hall’s “I Have A Dream” phrase would inspire King to start using it in his sermons leading to his famous “I Have A Dream” speech at the March on Washington.

Hall, who became a pastor, earned a Master of Divinity in 1982, a Master of Theology in 1984, and a Ph.D. from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1997. She joined the faculty at Boston University School of Theology in 2000 where she held the Martin Luther King Chair in Social Ethics. She died of cancer on August 12, 2002, in Boston, Massachusetts at the age of 62. Five years before her death, Ebony magazine named Hall number one on their list of Top 15 Greatest Black Women Preachers.

Dorothy Height

Civil rights activist Dorothy Height met King when he was 15. She became one of King’s trusted allies and confidants who worked with him to promote civil rights and equality. Her civil rights work was done specifically with Black women and Black women organizations and for forty years, Height led the National Council of Negro Women as the president, addressing the rights of both women and African Americans.

Described as the ‘godmother’ of the civil rights movement, Height was a key organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. That year, at King’s request, she led a group of people to Alabama to meet with the families of the four girls killed in the bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Height attended rallies with King and used her training as a social worker to reach out to families who were dealing with discrimination. In 1971, she helped found the National Women’s Political Caucus with Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan and Shirley Chisholm.

Photo: SNCC Digital Gateway

Ella Baker

Historians say that there would not have been an SNCC without Ella Baker. Following her early work for the NAACP, she was among the founders of King’s SCLC in 1957. She later helped launch the SNCC, where she worked alongside King and organized and mentored many young activists. She clashed with King and other male leaders of the SCLC because she felt she had a lot to offer but was “relegated to get coffee, get notes, run papers off in lithograph,” Tiffany Gill, an associate professor of Africana studies and history at the University of Delaware, told The Philadelphia Tribune.

Baker still participated in the movement and her “principles informed the generation of people whom King was able to mobilize,” according to Marcia Chatelain, associate professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University.

Mahalia Jackson

Known as the “Queen of Gospel Music,” Jackson met King in 1956 when King’s closest comrade, the Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, who was the director of the SCLC, invited her to support the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. She started joining King at civil rights events around the country and also supported the movement financially, putting her career and faith on the line.

“Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin, tell ‘em about the dream!” she shouted from behind the podium during King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington in 1963. Her words encouraged King, who redirected his speech during the event, leading to what is now one of the most famous speeches in history.