The plane door is opened as we wait on the tarmac in Dakar, Senegal. I approach it to inhale my first aroma of Africa, of home. I step near the door and take in the high grass that lines the landing strip, the bright sun that has been showing for about two hours, the blanket of June’s humidity, and the unfamiliar smell that assaults my nose.

SEE ALSO: Political Activist Remembers African Determination & Faith in Guyana During Early 1900s

Coming from my home of Las Vegas, where there is little vegetation, less humidity, and all asphalt that’s cooked by the blazing sun nine months of the year, I assume this is what true nature smells like. It is eerily quiet at this airport, something that I’m unfamiliar with as I’m used to flying major airports, such as McCarran, LAX, JFK. The plane staff asks everyone to take their seats as we have topped off the fuel and will be in the air momentarily to continue our flight to Bloemfontein, South Africa.

I am one of millions of Black Americans who don’t know their familial connection and bloodline to Africa.

Bucket List item #1: live and work in Africa.

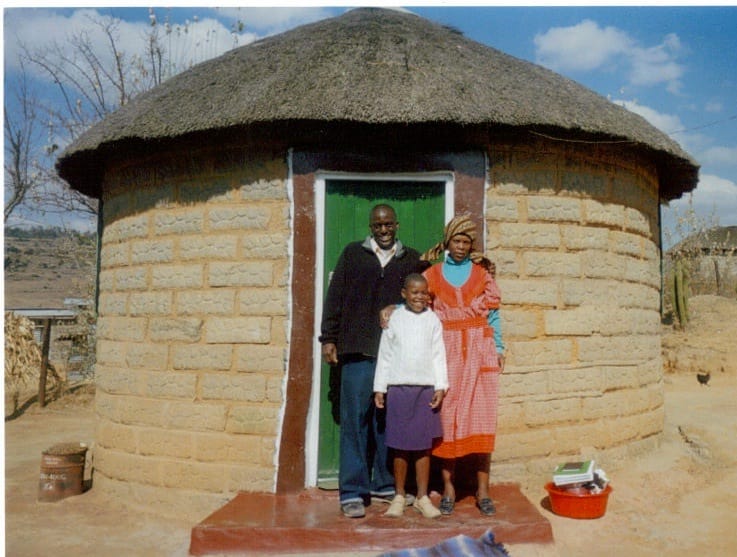

I figured it’d happen in my 40s but was blessed with an opportunity to work in Lesotho at the age of 23 as part of the U.S. Peace Corps.

In going, I didn’t know much about the small mountain kingdom enclave of Lesotho before stepping foot in it. When I became a U.S. Peace Corps Volunteer, I chose not to do too much research on Lesotho as I wanted my perspective of “Africa” on the ground to be based on my personal encounters and not the unfounded, fearful warnings of my family and friends. My mom was a little worried but moreso because her baby was traveling internationally for the first time.

From day one, I made it a point to do a lot of listening while having fun. Laughter is easy to come by if you let it be. While working at Selibeng Youth Centre (pronounced SEH-dee-bang in the local language know as Sesotho), I asked a lot of questions.

“How do you say this in Sesotho?”

“Why can’t I pick up that furry caterpillar?”

“Why do you think China has a textile factory in Lesotho?”

“Is half a loaf really better than no loaf?”

“Why can’t I leave the shovel standing up in the dirt?”

The great thing was that all of my questions were answered. The same way I asked questions incessantly of the Basotho, is the same way they asked of me as a Black American.

“Why does your hair feel different from ours?”

“Why are you skinny and not fat like all Americans on TV?”

“How can you not know your grandfather’s grandfather?”

“Which is better, kwaito or rap?”

“How much does a flat cost in Las Vegas?”

After having learned Spanish, I already understood the value of integration and access when it  comes to using someone else’s language. Taking this to heart kept me a student of Sesotho during my whole Peace Corps service.

comes to using someone else’s language. Taking this to heart kept me a student of Sesotho during my whole Peace Corps service.

My counterpart, Seipati Maphatsoe, was well-known in my camptown and across Lesotho. Me getting familiar with my area and the people had a lot to do with her. It seemed like everyone we came across knew this petite woman with the limitless energy. She knew how to connect with children, young and elderly adults, shopkeepers, shoemakers, businessman, taxi drivers, netball players. I hadn’t seen someone like her before, and just to be near her made your day better. Her indelible impression has lasted all these years.

After 27 months of lIving and working in the town of Mohale’s Hoek, I’m glad I made that decision. A high prevalence of HIV/AIDS, a severely depressed economy that resembled the American Dust Bowl, a fairly underdeveloped country — that’s what stood out. What connected me to my community and the people of Lesotho was my local language skills, ability to adjust culturally, and general physical appearance as a deep-hued (a.k.a. dark-skinned), thin, bald, Black American.

It was hard for Basotho (people of Lesotho) to believe I hadn’t returned “home.” I had to repeatedly explain to Basotho that there are plenty of dark-skinned people in the United States. I also had to explain that I didn’t know Robert Kelly (better known as R. Kelly), that I didn’t rap even though I love hip-hop, and that slavery’s effects are still deep and long-lasting despite the appearance of an America that is painted on the sliver screen as perpetually happy, sunny, and wealthy.

Connecting to my Basotho community was a life-enhancing experience like no other. It granted me access and favor that magnified our work as a youth organization and reaffirmed my belief in the power of language.

SEE ALSO: A Letter to the Offended Man Who Called Me ‘Racist’