Love is in the air. For many people, February 14, marking Valentine’s Day, is a day to show love, friendship, and affection through gifts, including cards, flowers, and chocolates. Even though the celebration originated from Western Christian traditions, it is now observed worldwide, with each country having its unique way of marking the day.

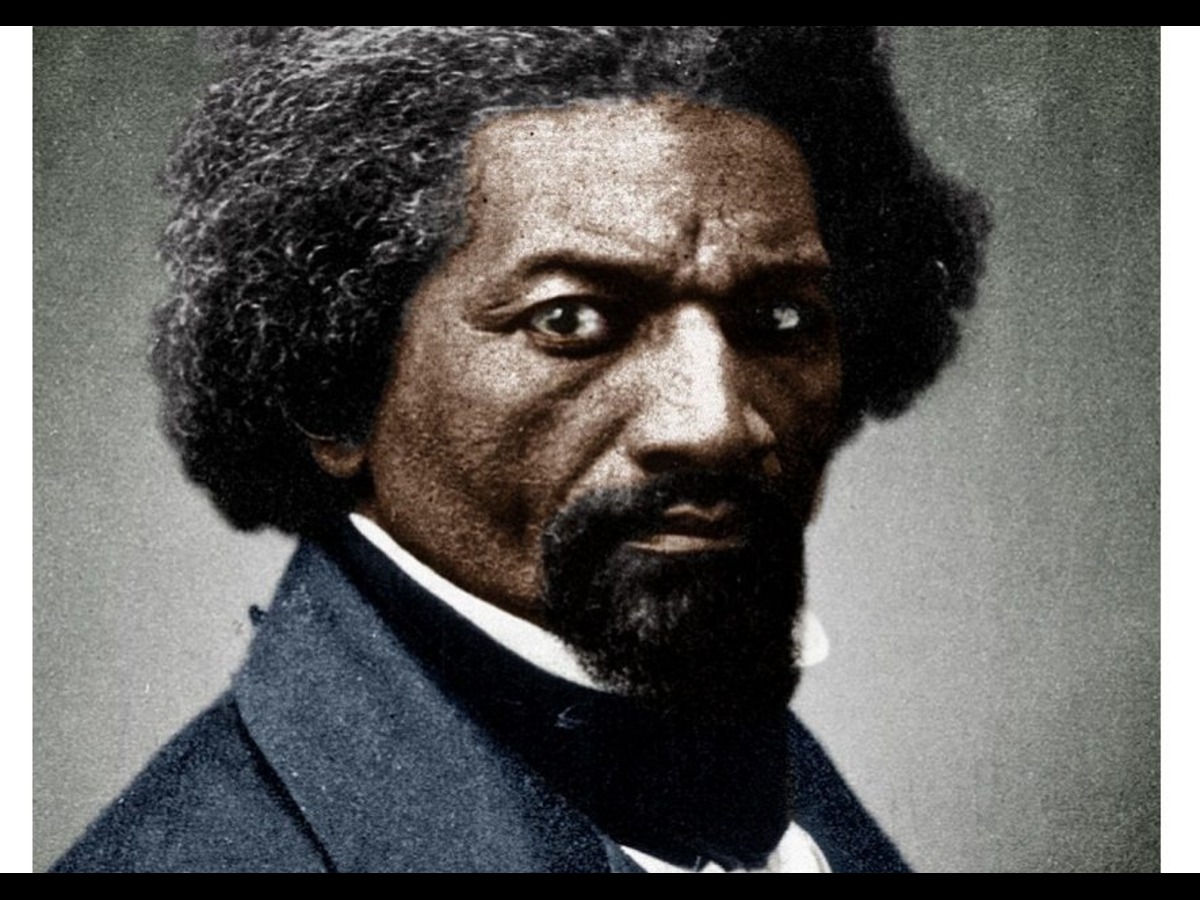

In America, February 14 also marks the birthday of the iconic Black leader, Frederick Douglass. A well-known abolitionist and preacher known for his command of language and prose, Douglass remains a towering figure in the annals of history for his long-established fight against the practice of slavery in America. Before he campaigned against slavery and fought for equality for African Americans, Douglass was in bondage. He was enslaved for the first 20 years of his life.

Born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, the actual day he was born is still unknown. Douglass, in his autobiography, believed he was born in the month of February in the year 1818.

The iconic leader also wrote about speaking in 1877 with Captain Thomas Auld, one of his former enslavers, on Auld’s deathbed.

“I told him I had always been curious to know how old I was and that it had been a serious trouble to me, to not know when was my birthday. He said he could not tell me that, but he thought I was born in February 1818.” Auld’s former wife, Lucretia, had also told Douglass that he had been born in 1817.

A ledger from Aaron Anthony, one of the men who also enslaved Douglass, showed the month and year Douglass was born, but there was no date. The birth ledger listed “Frederick Augustus son of Harriott, Feby 1818.” Preston believed the notation in the ledger was added at a later date.

Douglass was born as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey and his mother was Harriet Bailey. Douglass, in My Bondage and My Freedom, recounted his last meeting with his mother, who gifted him with a cake.

“The ‘sweet cake’ my mother gave me was in the shape of a heart, with a rich, dark ring glazed upon the edge of it. I was victorious, and well off for the moment; prouder, on my mother’s knee, than a king upon his throne,” he wrote.

Preston said Douglass may have later thought that his birthday was linked to Valentine’s Day. Some historians say one of the few memories Douglass had of his mother was when she called him her “little Valentine.”

Several people enslaved Douglass before he hatched a plan to escape. On September 3, 1838, Douglass, with the help of his partner Anna Murray, hopped aboard a railroad train heading north disguised as a free Black sailor.

He escaped to the free North and would end up in Rochester, New York, with Murray. Becoming a free man, Douglass got deeply involved in the abolition movement, and this made him travel widely to give speeches, including spending two years in Europe from 1845 to 1847. He started publishing his own abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, and moved with prominent abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison. People trooped in at venues just to hear Douglass speak.

On February 28, 1888, when the Bethel Literary Society in Washington, D.C. decided to honor Douglass for his birthday, he took the stage and said the following: “I understand from some things that have occurred since I came in that you have been celebrating my seventy-first birthday. What in the world have you been doing that for? Why Frederick Douglass. That day was taken from him long before he had the means of owning it.”

“Birthdays belong to free institutions. We, at the South, never knew them. We were born at times: harvest times, watermelon times, and generally hard times. I never knew anything about the celebration of a birthday except Washington’s birthday, and it seems a little strange to have mine celebrated. I think it is hardly safe to celebrate any man’s birthday while he lives,” he added, as reported by the National Constitution Center.

Douglass passed away in Washington, D.C., from what was believed to be a heart attack on February 20, 1895.

Despite rising from slavery to become a famed abolitionist and preacher, Douglass would have hoped to get a better understanding of his family roots, including his birthday.

Four years before he died, he was reported by Frederic May Holland as saying in a private letter: “It has been a source of great annoyance to me, never to have a birthday.”

Holland said, “He [Douglass] supposes that he was born in February 1817, but no one knows the day of his birth or his father’s name.”

The Washington Post, meanwhile, stressed that Douglass had decided throughout his entire existence to use Valentine’s Day to mark his birthday. “After he got his freedom he celebrated St. Valentine’s Day as his birthday, since he felt he had a good a right to have a birthday as other people, and he liked the traditions surrounding that date.”

Douglass’ birthday on February 14 is now observed annually as “Douglass Day”. As a matter of fact, the first Douglass Day was commemorated in 1897, just two years after the abolitionist’s death, by the District of Columbia Schools — a decision that was influenced by board member and activist Mary Church Terrell.