In January 1897, seven British officials, including leader and acting Consul-General James Phillips, were ambushed and killed on their way to see Benin King Ovonramwen or Oba. The murders caused the U.K. to respond with 500 soldiers of their own in what is now understood as “the most-brutal massacre of the colonial era.”

After deposing the King, soldiers pillaged and plundered the Benin Kingdom, stealing thousands of artifacts and artworks, with the majority of the spoils going to the British museum. However, Mark Walker (pictured below), recently decided to return two artifacts to the kingdom that were given to him by his grandfather, Captain Herbert Walker (pictured), re-exposing the fact that the British have still refused to return these priceless works.

SEE ALSO: India’s Rich African History Extended Far Beyond Slavery & Trade

Keep Up With Face2Face Africa On Facebook!

The Benin Empire, which is located today in the southern region of present-day Nigeria, controlled trade between Europe and the Nigerian coast from the late 1400s to the end of the 1900s.

Made out of brass, ivory, and coral, the art that came out of the Benin kingdom served a number of purposes: they were physical manifestations of the empire’s history and additionally expressed King Oba’s divinity and interactions with the supernatural.

The art that came out of this kingdom reportedly dates back to at least 500 BCE.

In 1897, when Phillips and his men were killed, the British answered back with a 500-strong force that used Maxim machine guns and rockets against the kingdom.

Retired doctor Mark says of the bloodbath, “The British had much better weapons so it was something of an uneven battle.”

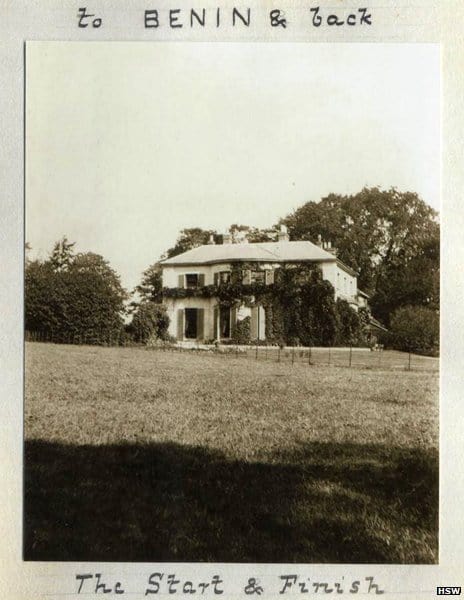

Mark’s grandfather fought among the ranks and wrote the following about the massacre in his “To Benin & back” diary (pictured) that detailed what was officially called the Benin Punitive Expedition:

The city is the most gruesome sight I’ve ever seen,” wrote Herbert. “The whole pace is littered with sculls & corpses in various stages of decay, many of them fresh human sacrifices. Outside the king’s palace were two crucifixion trees, one for men & the other for women, with the victims on & around them. As we approached the city through the bush, we found bodies of slaves newly sacrificed & placed across the path to bring the Benis luck, while they lay in holes, or behind cover, & ‘sniped’ at us as we passed.

According to Captain Walker, both men and women were sacrificed that day in an effort to appease the gods and foil the British attack.

Following the killing was the looting: More than 2,000 religious artifacts and artworks were stolen and taken to England.

Of the stolen works, Herbert described how a fellow officer was “wandering round with chisel & hammer, knocking off brass figures & collecting all sorts of rubbish as loot.”

In addition, all religious buildings and palaces were set on fire.

To date, the British Museum has 800 artworks that came directly from the Benin Punitive Expedition.

Meanwhile, King Oba was exiled to Calabar and by the time the monarchy was restored 17 years later, the Benin Kingdom was no more, and in its place was the newly colonized “Nigeria.”

But Captain Walker didn’t come away empty handed either: He took an Oro bird, which is known as the bird of prophecy (pictured), and a bell (pictured) that was used to invoke the ancestors.

And in 2013, Mark would inherit those items.

“I was surprised, having coveted them for so many years that when I finally came in possession of them I found myself asking what their future was.

“As you come in to your 60s, you realise you have got to start making preparations for moving away from this life. I was asking myself, What do I want them for? Possessions aren’t as important as I used to think when I was younger.”

After speaking with his children and realizing that they did not care to have the artifacts, Mark wondered about how to return the items to their actual home.

He came across the Richard Lander Society, an organisation that campaigns for the Benin artworks to be returned to the royal palace in Benin City. It helped him contact the right people and last year Walker travelled to Nigeria to hand the bronzes to the present Oba (pictured), the great-grandson of the King deposed by Herbert and his colleagues.

“It was very humbling to be greeted with such enthusiasm and gratitude, for nothing really. I was just returning some art objects to a place where I feel they will be properly looked after,” says Mark.

Obviously, Mark’s bird of song and bell aren’t just “some art objects,” though.

“Those things that were removed were chapters of our history book,” says Prince Edun  Akenzua, a younger brother of the current Oba.

Akenzua, a younger brother of the current Oba.

“When they were made, the Benin people did not know how to write, so whatever happened, the Oba instructed the bronze casters to record it.

“We saw the removal as a grave injustice and we are hoping that someday people will see why we are asking for these things back,” he says.

Clearly, Mark’s contribution isn’t even the tip of the iceberg in regards to what was lost by the Benin Empire.

Consequently, Prince Edun has been reportedly lobbying British Parliament to return all of the looted artworks and artifacts to Benin City.

Prince Edun adds, “The English returned the Stone of Scone to Scotland some years ago. So why can’t they return our things? They mean so much to us but they mean nothing to the British.”

Not surprisingly, there is resistance to returning the works, with some oddly arguing that sending them back to Nigeria would actually be putting them in danger.

To that, Prince Edun quips, “It’s a bit like if someone were to steal my car in Benin City, and I found it in Lagos and could prove that it was mine. And the thief told me, ‘OK, you can have your car back if you can convince me that you’ve built an electronically controlled garage to keep the car. Until you do that, I will not return it to you.'”

Meanwhile, at press time, the British Museum claims that they haven’t received any “recent” requests for the nearly 1,000 artworks and artifacts they possess from the Empire.

In a statement, the museum added:

“As a museum of the world for the world the British Museum presents the Benin Bronzes in a global context alongside the stories of other cultures and makes these objects as available as possible to a global audience.”

SEE ALSO: REPORT: HUNDREDS MORE OF AFRICAN AMERICANS LYNCHED THAN PREVIOUSLY THOUGHT