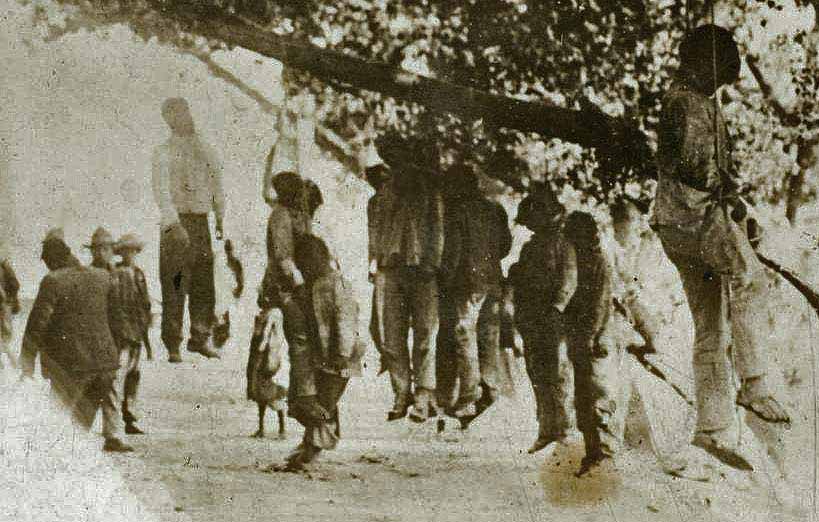

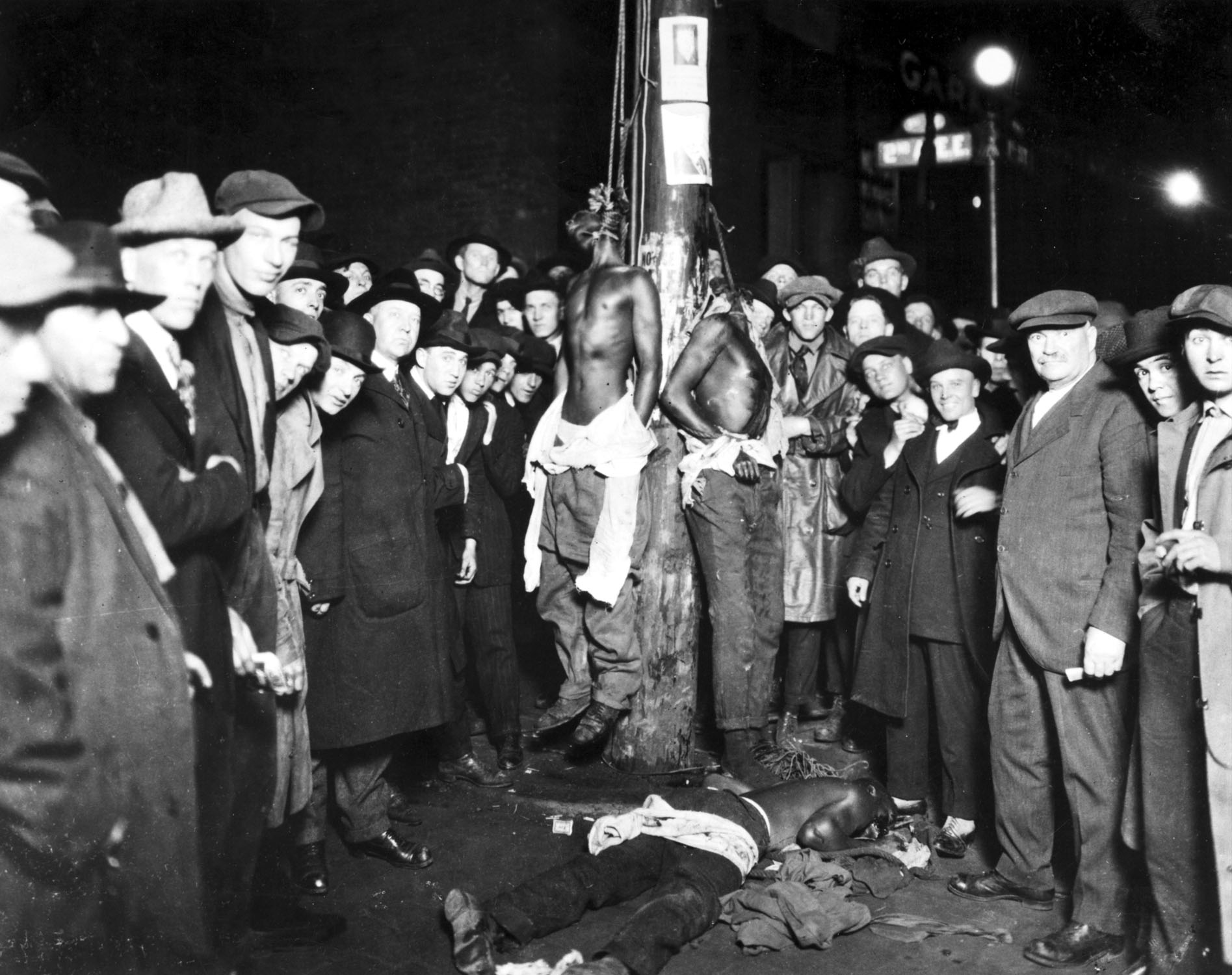

While African-American communities throughout the United States continue to reel over the police shootings of Black men, nonprofit organizations, such as the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), say that the discrimination and skewed perception of Blacks in American society is in due part to the history of lynching of African Americans. On Tuesday, the Montgomery, Alabama-based EJI, released a detailed report, entitled, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.” The report notes that there are at least hundreds of lynchings that occurred after the Reconstruction period until after the Second World War that went not only unreported, but also ignored, ultimately shaping the often combative racial experience between Blacks and Whites in the United States.

SEE ALSO: Several Factors Caused U.S. To Explode in Aftermath of #MikeBrown Police Murder

Lynching is the practice of killing a person or a group of people by a mob usually by hanging. The murder of Blacks, though, also happened by way of beatings, burnings, and shootings.

According to EJI’s report, from the years of 1877 to 1950, 3,959 men, women, and children were lynched throughout 12 southern states.

Their calculations actually recognize about 700 more lynchings than previously thought.

In order to personalize the local terrorism happening against Blacks during the time, EJI underscore the murder of soldier William Little.

Ironically, while Little managed to survive the battle fields of World War I; by 1919, when he returned to his home of Blakely, Georgia, he would meet his violent end there.

In author Carl Cannon’s book “The Pursuit of Happiness in Times of War,” he writes:

“The year 1919 was a time of resurgence by the Ku Klux Klan. Seventy-six Blacks lost their lives to mob violence in southern states that year. One of them, Private William Little of Blakely, Ga., was apparently lynched precisely because he was wearing his uniform.

“The accounts of the time state that a few days after being mustered out, he took a train home and was beaten by local Whites for wearing his uniform around town.

“The mob made him remove it.

“A couple of days later, he was caught wearing it again — Little protested that he had no other clothes — and was beaten to death and left at the end of town.”

But rather than these “terror lynchings” being remembered and taught as a cautionary tale of America’s dark past, this period has largely remained ignored.

14 photos

The sites of nearly all of these killings, however, remain unmarked in what the report calls an “astonishing absence of any effort to acknowledge, discuss or address” the violence that occurred.

Consequently, EJI spent five years piecing together this painful period in order to force Americans to face this history as well as dignify the thousands that lost their lives.

The organization plans to build monuments and memorials and place markers of the dead where this violence took place.

EJI Director Bryan Stevenson explains, “We want to change the visual landscape of this country so that when people move through these communities and live in these communities, that they’re mindful of this history. We really want to see truth and reconciliation emerge, so that we can turn the page on race relations.

“We don’t think you should be able to come to these places without facing their histories.”

Through EJI’s vantage point, that is why these “terror lynchings,” as they call them, sought to “enforce racial subordination and segregation.”

Of their effects on the Black community, Stevenson says, “It’s important to begin talking about it. These lynchings were torturous and violent and extreme. They were sometimes attended by the entire White community. It was sometimes not enough to lynch the person who was the target, but it was necessary to terrorise the entire Black community: burn down churches and attack black homes. I think that that kind of history really can’t be ignored.”

Not acknowledging and facing the history of the lynching of Blacks in the United States of America is the reason, in Stevenson’s view, that racism continues and is part of the reason Blacks are still targeted in society by White law enforcement, i.e., the high-profile cases of slain victims Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Ramarley Graham, Eric Garner, Sean Bell, Amadou Diolu, and more.

“The failings of this era very much reflect what young people are now saying about police shootings,” Stevenson said. “It is about embracing this idea that #BlackLivesMatter. I also think that the lynching era created a narrative of racial difference, a presumption of guilt, a presumption of dangerousness that got assigned to African Americans in particular – and that’s the same presumption of guilt that burdens young kids living in urban areas who are sometimes menaced, threatened, or shot and killed by law enforcement officers.”

Listen to jazz icon Billie Holiday’s ode to lynching in “Strange Fruit” here:

SEE ALSO: Why #MichaelBrown Matters : Unarmed Blacks Repeatedly Killed By Police, ‘Scared’ Citizens In America