An all-Black South African rowing team recently made history by competing in the Head of the Charles Regatta in Boston, United States. This marks the first time a minority crew from South Africa has participated in the world’s largest three-day rowing event.

Rower Lwazi-Tsebo Zwane and his teammates, Lebone Mokheseng, Sepitle Leshilo, and Sheldon Krishnasamy, competed against some of the world’s top rowers, including those from prestigious U.S. universities.

Zwane expressed surprise upon learning of their groundbreaking achievement.

“In terms of minority crews as a whole, to be one of the first and few is … it feels like we’re making history. For me, it’s life-changing, a bit surreal,” he was quoted by Africa News.

According to their coach, Michael Ortlepp, their presence in Boston serves as an inspiration, demonstrating to the younger generation what is possible to achieve.

“I think it’s incredibly important for individuals to have people they can look up to, which they haven’t necessarily had previously,” he said.

The participation of the South African rowing team aims to broaden access to an elite sport predominantly featuring White athletes. However, Ken Gliddon, the president of Western Cape Rowing who is behind the idea to send a team to the race, emphasized that the team was chosen based on merit, not for appearances.

Zwane expressed his honor in being considered a “guiding light” for younger South Africans, highlighting the importance of demonstrating that their origins do not define their limitations. The crew hopes its involvement in the Men’s Championship 4+ event will motivate the next generation of South African rowers.

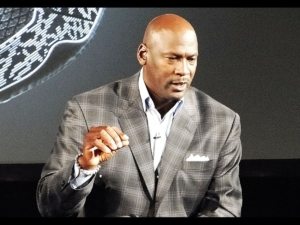

Arshay Cooper’s foundation helped the South African crew and underrepresented U.S. athletes get to the Charles regatta. Cooper pointed out that rowers in both America and South Africa who aren’t white or from wealthy families face similar challenges, as reported by AP.

Limited access to waterways and essential skills like swimming, coupled with the high cost of equipment (rowing shells alone can cost tens of thousands of dollars), are significant challenges.

“There’s structural limitations, there’s neglect,” said Cooper, who joined America’s first all-Black high school rowing team in Chicago in 1997. “There’s talent everywhere, but not a lot of access and opportunity.”

Public schools in both countries, often attended by athletes of color, provide some access to rowing programs. However, these programs typically suffer from outdated equipment and less experienced coaches, hindering their ability to compete with better-resourced private schools.

Competitive rowing, as it’s known today, originated in the 19th century at prestigious British institutions such as Oxford and Cambridge. It later spread to elite American universities like Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Historically, these institutions excluded individuals from working-class backgrounds, as well as those who were not white or male. The typical rower is usually seen as “white and come from a middle or upper class suburban community, per a 2016 analysis by U.S. Rowing.

READ ALSO: Amina Orfi: 17-year-old Egyptian makes squash history

According to Cooper, the aim is to introduce new participants to the sport. Occasionally, these new participants use the platform to draw attention to social issues.

Coach Ortlepp sees firsthand the huge sacrifices many university athletes he coaches in Cape Town have to make.

These athletes, mostly from formerly segregated townships, deal with unreliable public transportation and housing issues, which makes getting to practice a real struggle. Ortlepp often gets messages from rowers who can’t make it to practice because of gang warnings and shootings in their areas.

Thanks to some financial help from Cooper’s foundation, they’ve set up a bus service to get athletes to practice. This support has been a game-changer, helping Ortlepp’s Association grow from just eight rowers to 45 in only three years.