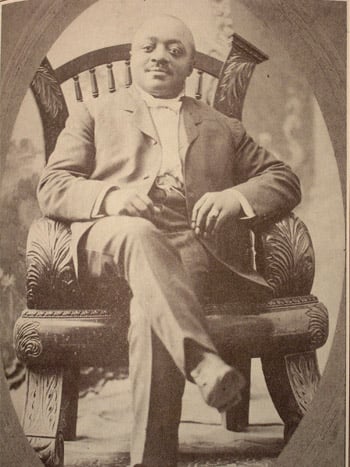

Policy Sam alias Samuel Young is remembered for bringing the illegal numbers game ‘Policy’ to Chicago in 1885 along with his associates Patsy King, a white man and an Asian named “King Foo”. Its scale was not as huge given it was in its teething years.

“Policy players tried to guess three numbers from 1 to 78 that were drawn from a tumbling drum, or “wheel.” Bets were taken by “writers” who canvassed the neighborhood, or placed in policy offices scattered throughout the community. From cigar stores and garages to barber shops and apartments, policy offices were set up anywhere there was space.

“It was an illegal game of chance similar to today’s state lottery. During its heyday, the game was an integral part of life in the black community. People played every day, sometimes several times a day, in the hopes of “hitting the numbers” and winning big. The large amount of money that was played on the game made policy a big business that had a strong influence on the local economy and city politics.”

Born to a black mother and an Italian father, ‘Tough’ Teddy Roe serving as a lieutenant of the Jones Brothers will battle the Italian mafia from controlling the South Side racketeering numbers. He came to Chicago by 1929 and then got involved in the policy business. The Policy game proved to be one of the most profitable criminal markets in the United States.

The Black Policy Kings of Bronzeville prevailed against the Chicago mob known as the Outfit. The kings will go ahead and forge a multimillion dollar policy business or numbers rackets. The relationship between writers and players was direct and with hopes of using a nickel to land a windfall, the game boomed.

Its success of the 1930s, 40s and 50s eventually led the state to move in setting up the state lottery and forced end of the reign of the kings through death or retirement. Roe was the last boss who was eventually gunned down. He was reportedly killed outside his South Michigan Avenue home by a white syndicate hitman. The gangsters then took over the black racket. Other bosses when leaned on gave in or got killed but Roe insisted “They’ll have to kill me to take me.”

The Jones Brothers comprising Edward, George, and McKissack (Mack), started out small, running a policy station from the back entrance of their “Jones Brothers Tailor Shop.” Led by senior brother Ed, the Jones trio turned a nickel game into a sophisticated business enterprise, which included the Jones Brothers Ben Franklin Store on 47th Street, the world’s only black owned department store.

Edward led negotiations for the forming of the 12 Policy Syndicate in 1932 which served as a council of sorts for policy matters. With an overwhelming number of blacks being Republican at this stage, democratic leaders Patrick Nash and South Side boss Joe cut a deal with Edward that if they he could swing the black vote for the democratic party, they would enjoy their protection to run the policy game.

“In 1946, the Jones Brothers were at the top of the $25 million-a-year policy syndicate in Chicago. The three brothers made high level civic and social connections, but the glamorous and lavish lifestyle of the Jones boys couldn’t be separated from the criminal activity that created it. Kidnappings, death threats, corrupt politics, violence, and jail time were also prominent in the brothers’ lives.”

Nonetheless money from the policy bankrolled many businesses, politicians, clergy, entertainers, sports figures and even law enforcers. The game was also a source of employment for runners, writers, pick up men and women, collectors and station operators. It created employment for thousands of people including book keepers and office workers. At least 10,000 people were involved in the business according to some estimates.

It’s said the nation’s 12 certified accountants worked in the policy business while dozens of lawyers were kept on a retainer.

Money derived from Chicago’s lottery or policy game also financed banks, insurance companies, restaurants, Provident Hospital, Negro baseball league teams and even a cemetery.

The respected author and poet, Richard Wright said of the Policy Kings: “They would have been steel tycoons, wall street brokers and auto moguls had they been white.”

In 1938, the Time magazine described the South Side of Chicago also known as Bronzeville, the Policy King’s engine as the centre of black business in the United States.

Business was so good; the Jones Brothers became the richest faintly in America at a time. However, the Feds had their eye on the brothers and in 1941 made their move but Ed Jones took the fall for his brothers and was sentenced 18 months on tax evasion charges.

Policy also inspired at least one spinoff industry — the publication of “dream books” that were touted for providing clues to a winning number.

Edward Jones was kidnapped, reportedly by white gangsters. Securing his freedom with a $100,000 ransom, Jones and brother George moved to Mexico. A third brother, McKissack Jones, was killed in a car accident. “Few other policy bosses died so prosaically during the years that the syndicate moved in,” the Tribune observed of an era of mob warfare the city hadn’t seen since Prohibition.

At its height, The Chicago Daily News estimated that $18,000,000 a year was being bet on Chicago’s policy wheels. The Negro in Illinois Writers Project estimated that on the South Side there were 4,200 policy stations and 100,000 people played on the West and South Sides combined.

“Despite its popularity, many considered policy to be a scourge in the black community. Policy perpetuated corruption in city government and also created its share of abhorrent, violent, criminal activity in the community. But in a segregated city where access to financial capital was scarce, the illegal enterprise was also a powerful economic engine. It helped drive the growth of many legitimate black businesses, created jobs, offered financial support for civic activities, and provided patronage for the arts.”

Other notables of the policy era span John ‘Mushmouth’ Johnson, Gus Greenlee, Alex Pompez, Bumpy Johnson, Casper Holstein and Madame St. Clair. Policy came to an end with the launch of the Illinois State Lottery in 1974.