In 1968, Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman (born Albert Cleage, Jr.) was described, alongside Jesse Jackson, Julian Bond, Eldridge Cleaver and Dick Gregory, as one of the “men who are speaking to black America.” Agyeman was then one of the most well known and influential leaders in the city of Detroit, empowering African Americans politically, economically and spiritually.

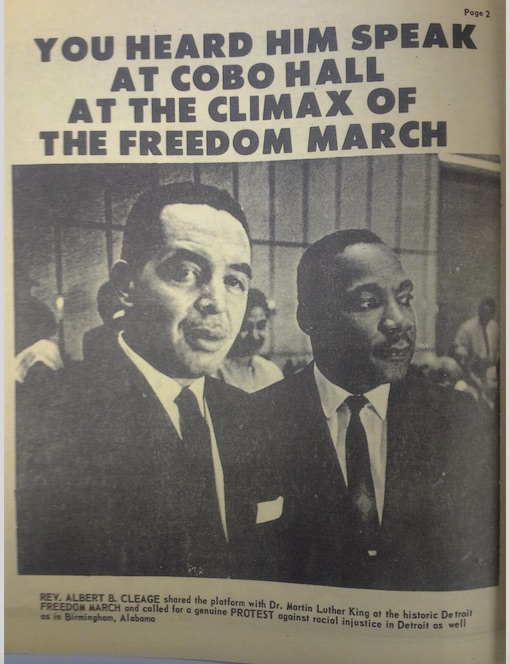

Working alongside iconic civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, Agyeman preached a gospel of black nationalism that stressed economic self-sufficiency for black people.

Leading the Shrine of the Black Madonna, originally a Congregational church, he is mostly remembered for his unveiling of a black Madonna holding a black baby Jesus. Agyeman would go on to preach that Jesus was a black revolutionary who sought to lead a “Black Nation” to freedom.

Gradually, the whites began to fear him as he worked towards advancing the lives of his followers and black people in general while marching for civil rights.

“He was able to re-Africanize Christianity or Christian theology,” said Kefentse Chike, a lecturer in Wayne State University’s Africana Studies department. “Part of what he did from a theological perspective was reconnect Christianity to its African roots and give it an African interpretation, and in a sense, rescue it from what White supremacy had done to it.”

Born in Indianapolis in 1911, his father, who was a physician, moved the family to Detroit. In 1937, Agyeman received a sociology degree from Wayne State University and his Bachelor of Divinity from Oberlin Graduate School of Theology in 1943.

Having served churches in Lexington, Ky. and San Francisco, he returned to Detroit in 1951 and soon became a pastor at St. Marks United Presbyterian mission. After serving the church for two years, he left with a group of followers to form the Central United Church of Christ, which would later become the Shrine.

His church ministered to the oppressed, and offered several programs for the community’s poor. Essentially, his concept of a church as the focal point of the community, particularly in terms of politics and education, began as his members supported the civil rights movement at the time, including the 1963 “Walk to Freedom” which Agyeman codirected with civil rights leader King.

Then in 1967, Agyeman did what was said to be “the beginning of a whole new religious iconography”; the installation of an 18-foot painting of a Black Madonna on an Easter Sunday in Detroit.

“For nearly five hundred years the illusion that Jesus was white dominated the world,” Agyeman preached during church service that day. “The resurrection which we celebrate today is the resurrection of the historic black Christ and the continuation of his mission. The church which we are building and which we call upon you to build wherever you are, is the church which gives our people, black people, faith in their power to free themselves from bondage, to control their own destiny, and to rebuild the Nation.”

Following the service, he formed the Black Christian Nationalist Movement and called for black churches to reinterpret Jesus’ teachings to suit the social, economic, and political needs of black people.

His movement attracted scores of people in the city and soon, he became one of the influential leaders of the black nationalist movement in Detroit largely due to his teachings and political activism.

His work the Black Messiah (1968) detailed his vision of Jesus as a black revolutionary leader whose identity had been masked by whites.

“Jesus was the nonwhite leader of a nonwhite people struggling for national liberation against the rule of a white nation…. That white Americans continue to insist upon a white Christ in the face of all historical evidence to the contrary and despite the hundreds of shrines to Black Madonnas all over the world, is the crowning demonstration of their white supremacist conviction that all things good and valuable must be white,” Agyeman was quoted as saying in his biography.

Alongside his Black Christian Nationalist Movement which later became known as Pan African Orthodox Christian Church (PAOCC), Agyeman established black-owned businesses including bookstores and grocery stores as well as scores of units of housing.

He was also instrumental in the early careers of many African-American politicians in Detroit, including that of the city’s first African-American mayor, Coleman Young.

It was during this same period – in the 1970s – that he changed his own name (Albert Cleage Jr.) to Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman, meaning “liberator, holy man, savior of the nation”.

In the 1990s, Detroit’s Shrine of the Black Madonna began witnessing a decline in membership even though similar shrines had been established in Atlanta and Houston. Agyeman had then begun focusing more on church programs and working with young people instead of being in the spotlight.

In February 2000, while visiting Beulah Land, the church’s new farm which was to provide food for the needy, Agyeman passed away at the age of 88. He is survived by two children.

His PAOCC continues its mission “to uplift and liberate the Pan African world community through the teachings of Jesus, the Black Messiah.”