Today, Liberia is going through the extreme agonies of the Ebola disease and losing dozens of citizens, and President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first woman head of state in Africa in modern times, is facing the challenge with encouraging resolve.

SEE ALSO: Guyanese Pan-Africanist, Activist Remembers 1960s Sierra Leone

Keep Up With Face2Face Africa On Facebook!

In 1965, I visited the Republic of Liberia because it had a different foreign policy from that of Ghana and Mali, and the western powers at the UN could often rely on its vote for Cold War issues.

I wanted to find out why.

Liberia belonged to the “Monrovia Group” of African states, with very moderate nations, and kind of stood in opposition to the “Casablanca Group” that included Ghana (Kwame Nkrumah), Guinea (Sekou Toure), Mali (Modibo Keita), and Algeria (Ben Bella). What distinguished the two groups apart were issues between the two power blocs headed by the United States and the Soviet Union, respectively.

The Casablanca Group was non-aligned, and since they voted for a change or shift in the international balance of power, their votes often disappointed Western powers.

Still, the two Pan-African groups belonged to the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and stood for the abolition of Apartheid and the colonial system.

I found Liberia almost as it was at its founding in 1947, a U.S.-patterned republic with a state  system, where the Americo-Liberians were clearly dominant just as Whites were in the United States. U.S. currency was the money in circulation, and it had its own state department with the typical dominance. It also hosted the most-powerful radio station on the continent thanks to a foreign Christian denomination. The nation also had Firestone Corporation, the rubber king, which was said to have as much influence as Congress and then-President William Tubman (pictured).

system, where the Americo-Liberians were clearly dominant just as Whites were in the United States. U.S. currency was the money in circulation, and it had its own state department with the typical dominance. It also hosted the most-powerful radio station on the continent thanks to a foreign Christian denomination. The nation also had Firestone Corporation, the rubber king, which was said to have as much influence as Congress and then-President William Tubman (pictured).

I saw President Tubman in his presidential office without having to bow many times as the foreign media would have us believe. He seemed unaware of imperialism and neo-colonialism but spoke passionately about “liberty.” He presented me with his book, “The Speeches of President Tubman,” and sent his greetings to the new Prime Minister of Guyana.

There was not much in-your-face political discussion in Liberia, or to be correct in Monrovia. I had read about the noted Vai community and tried to find a link to them. The official in the state department thought I was interested in the famed beauty of the Vai women, though, calling them “girls.”

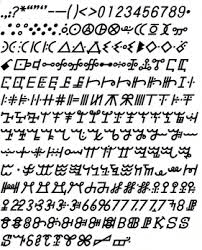

Instead, I told him I was interested in the Vai script (pictured), an indigenous alphabet, which had been unearthed and published possibly by the so-called missionaries. It took me three days of visits to institutions of museum and libraries before I actually ran in to a Vai woman in the Ministry of Information. She said, “I am one of them.”

I told her about my search for the alphabet, and she was very pleased. She said I should see Old Man Kandakai, who was the real custodian of the script, but he was too ill to be visited. “But come here tomorrow and I shall have one for you.” And when I returned the next day, the woman had it ready.

It was a real prize for me to take back to Guyana with an indigenous African script from a continent, which according to some European historians, never had writing.

Their scholars have spent decades translating Egyptian hieroglyphics and reading the “coffin texts” but still they insist there was no writing in Africa!

Meanwhile, Liberia offered me its own education in world culture.

The officials took me one day to Bomi Hills (pictured), the site of an important iron ore deposit in which the Dutch were interested. While the man from the state department was pointing out to me the sparse dress of the indigenous people in the hot sun, I was noticing something else:

We passed close enough to some of them to see that they wore ornaments of iron. Yet he and his class called them “uncivilized.”

Yet in terms of scientific development, the excluded communities of Liberia in 1965 were more advanced than the bulk of the Americo-Liberians who had made the country their home but could not smelt iron.

OOPS!

There was one Guyanese I met in Liberia. He was Dr. Josh Jupiter of Golden Grove, which is a post-emancipation village in Guyana. He had left Queens College, gone abroad, and studied dentistry, which he practiced in Liberia.

Another strange. indirect link with Guyana was a woman at the desk at the hotel. Seeing my passport, she wanted to know whether I knew the whereabouts of her father. He had fathered her with a Liberian Mother while he was a British diplomat in Liberia and he had, in fact, worked in Guyana about a decade earlier.

I promised to try to locate his posting.

These officials were the people sent out by Britain to the colonies to tutor colonials in administration and morals. There was one other big moment of realization for me. I accepted an invitation from the state department officials to attend a cultural evening at “The Liberian Jungle,” clearly a venue not so much to celebrate the jungle as to ensure tourist entertainment.

That night I saw the most-highly accomplished production I have ever seen.

The production was called “The House of Daws,” and it told a story in music, dance, and atmosphere — all three impressive and of engaging beauty. The Americo-Liberians who took me there were astonished when I remarked that this was ballet at least as rich as those I had seen in Eastern Europe in 1952.

I left Liberia not long after, but not before reading in a library several papers by Germans, other scholars, and the then-living and active W.E.B. Du Bois.

I could not leave without stealing along a winding path through a slum of Monrovia, where two things impressed me: I could see very clearly a household sitting on the floor eating a meal, dipping from a common dish in their midst. From another small house came the strains of the Ghanaian high life song “Work and Happiness.”

The physical air and atmosphere and the earth itself were pure, war had not come, and there was no news of an epidemic….

SEE ALSO: Pan-Africanist, Activist Remembers Guyanese Support of Angola