I hated studying history at school. I couldn’t wait to get to year nine, so I could drop it when I selected my GCSE options. More recently, however, I have grown to understand just how important history is.

I hated studying history at school. I couldn’t wait to get to year nine, so I could drop it when I selected my GCSE options. More recently, however, I have grown to understand just how important history is.

SEE ALSO: Political Activist Offers Snapshot of African Experience During Guyana’s Slavery Period

History contextualises the present. When I write of history in this article, I write not of a romanticised nostalgia of the Tudors and the Victorians, which added minimal, if any, value to my life.

Instead, I write of the gross injustices that still have residual effects on individual lives even today, of which slavery, colonialism, and racism are prime examples.

Although slavery, colonialism, and racism are phenomena often viewed as outdated and no longer relevant to speak of, the unfortunate reality is the complete opposite.

I truly have trouble believing that anyone is analytically inept enough to genuinely fail to see how these histories still affect diasporas in the present day.

Everywhere. Unfailingly.

As such, a part of me believes that people simply refuse to acknowledge and accept this reality.

But just in case, please allow me to illustrate, even though the residual effects of slavery, colonialism, and racism are too numerous, varied, and context-specific to compress into a given amount of words.

Obviously, the effects will be different for an adult living in sub-Saharan Africa, a Black teenager living in the USA, and an Asian child living in the U.K.

As such, they need to be dealt with very tenuously, but for the purpose of this article, please read on for a more general exploration.

Economic Structures

“Great” Britain and the United States today became the economic giants that they are through the theft of African resources and the forced labour of African people.

Consequently, many parts of Africa suffered and continue to suffer great economic injury through the depletion of our rich resources and the abuse of our lands.

Nearly 70 percent of the poorest countries in the world are in Africa, 64 percent of children in sub-Saharan Africa do not have adequate sanitation, 57 percent of African children are enrolled in primary education, and one in three of those do not complete school.

The facts go on.

People often depict African leadership as naturally predisposed to corruption and as always incapable of managing themselves.

Yet pre-colonial history shows that the empires of Africa, though not always without conflict, were highly efficient and had great riches.

It was through the divide-and-rule strategy of the colonialists — magnifying “differences” between tribes and pitting them against each other — that many of our great kingdoms were broken down.

When the colonialists retreated from our lands, we were left in disarray, often with no stable leadership in place, and this has had disastrous and long-lasting repercussions and led to all sorts of conflicts.

In contemporary society, the exploitative regimes that existed in colonialism persist. As recently as 2006, Dutch-based oil company Trafigura Beheer BV deposited more than 500 tonnes of toxic waste in the poor suburbs of the Ivory Coast in order to evade the large costs associated with legitimate and safer disposal in the Netherlands. More than 30,000 Ivorians were injured.

Black/African lives are still perceived as dispensable within this capitalist system and as secondary to monetary gain.

Francophone countries, such as Senegal, Togo, Benin, Ivory Coast, and Cameroon are still mandated to pay “colonial debts” to France even today.

This so-called “debt” is based on the claim that these Francophone countries should pay for the infrastructures built by France that they now benefit from – like they were ever invited to “build” in the first place.

France automatically confiscates national reserves of many of its ex-colonies. Jacques Chirac, former French president, said, “Without Africa, France will slide down in to the rank of a third [world] power” (March 2008).

Domestically, the case is similar. Unemployment is rife among Black men, and they are the most-underemployed group in the United States and the U.K.

Too often cultural factors are cited to explain this discrepancy in employment opportunity, however, rarely are the structural factors inhibiting Black men from securing stable and meaningful employment acknowledged and explored.

The racist colonialist discourses that caricature Black and ethnic minority men as lazy and unintelligent enough to work still hold sway over the public imagination.

Ethnic minorities are more likely to live in poor areas, be poor, be unemployed, suffer ill health, and live in overcrowded or unpopular housing than the White indigenous population (Social Exclusion Unit, 2000).

Legal System

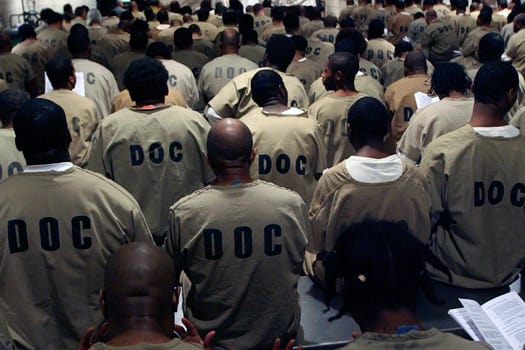

Black and ethnic minority men are disproportionately imprisoned and otherwise represented in the criminal justice system.

And the figures are bleak.

Statistics from the Equality and Human Rights Commission show that Black prisoners make up 15 percent of the U.K.-prisoner population, compared with just 2.2 percent of U.K. residents (EHRC, 2011).

This pattern is also observable in America, where Black and Hispanic prisoners accounted for a startling 58 percent of the prisoner population in 2008 compared with about 25 percent of the general population (NAACP, 2010).

In the U.K., Section 60 stop-and-search procedures are more common in working-class areas with greater ethnic diversity.

While most people simplistically respond, “These men should stop committing crime then,” they ignore the fact that the definitions of “crime” and “criminal” are not stable and self-evident, but instead, are continually evolving over space and time.

People point toward the “broken Black family” as an explanation of why young Black men are more inclined to “crime,” forgetting that the Black family was systematically disassembled by the sexual exploitation of Black women, the infantilisation of Black men, and the deliberate separation of Black family units.

Furthermore, places, such as Britain and the United States — who are both historically and presently guilty of heinous crimes and human rights violations — developed laws and created “crimes” that privileged Whites and condemned ethnic minorities.

W.E.B. Du Bois’ assertion that it was “… color that settled a man’s conviction on almost any charge” highlights the fact that perceptions of suspicion are informed by racist discourses.

Slavery was once institutionalised, as was segregation. By institutionalised, I mean it was central to how society operated; it was written in to law; it informed social organisation in arenas from education to enterprise.

The abolition of slavery was not unanimously agreed upon; there were people who wanted to keep White supremacy in place.

When slavery was abolished, southern states used the criminal justice system to legally restrict the possibility of freedom for newly released slaves.

Unemployed Black people (who were many, considering the circumstances) were called “vagrants” and were incarcerated, having to undertake forced labour.

This was instituted in order to regulate the behaviour of free Blacks. For example, trivial offences of Blacks, resulted in harsh sentences and fines.

Today, Black communities remain “under-protected and over-policed,” with Black victimhood being largely overlooked and the definition of “crime” and “criminal” being conflated with Blackness: Black offenses are disproportionately focused on above all other demographics.

Identity

A wide array of identity crises have arisen from a long history of slavery, colonialism, and racism.

For example, there are Africans I’ve met who welcome the return of colonial presences in Africa, as they believe we are incapable of governing ourselves. They proclaim to love the West and hate Africa, because “nothing good can come of Africa.”

This is tragic to observe.

There are also Black people who deliberately disassociate themselves from other Blacks in attempts to increase their symbolic proximity to Whiteness as much as possible, because Whiteness is still often seen as superior.

This can be observed when Blacks and ethnic minorities bleach their skin in order to get closer to the European ideal of beauty.

The problematic perception and treatment of racialised ethnic minority demographics at both an institutional and individual level has long-lasting detrimental effects on the development of the “self” and on “race” and class-consciousness.

Colonialism and its residual impacts does damage to both the identities of groups and individual subjectivities (Fanon, 1967).

Conclusion

This is but a brief introduction to the many residual effects of slavery, colonialism, and racism and doesn’t even scratch the surface of these deep-rooted problems.

“They don’t talk about why things are the way they are. They hide the bloody past of the British Empire as much as they can. It’s ‘Great Britain,’ but they take out the ‘empire’ bit, so we don’t know how Britain became so great.

“We learn about the Victorians and we learn about the industrial revolution, but we don’t learn what was funding the revolution in the first place.

“We didn’t learn that while there was this booming revolution in England, there are people from Britain in India in Nigeria murdering and colonising the people.” – Abraham Popoola

I am not advocating here a fixation on the past while neglecting the present and the future. Rather, I am asserting that acknowledging the way slavery, colonialism, and racism remain injurious today is a prerequisite to mapping out routes to progression.

The key to properly solving a problem is identifying its root. This is the starting point of any fruitful dialogue.

Finally, when referring to colonialism and racism, I do not speak of things of the past. Colonialism and racism have been succeeded by neo-colonialism and new forms of racism.

We must subsequently use this knowledge that we have been and continue to be systematically disadvantaged to effectively put our own strategies in place for our own progression.