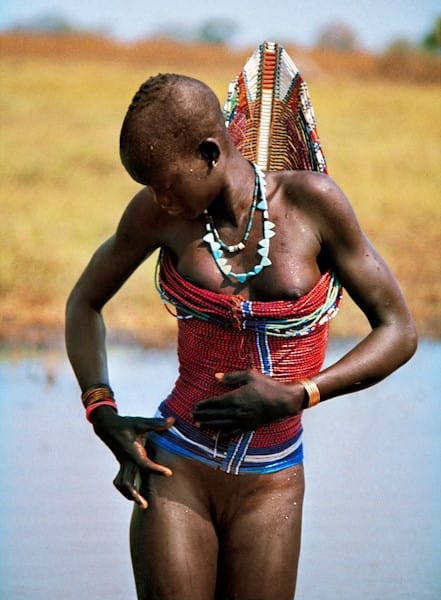

Photo by Carol Beckwith & Angela Fisher: “In the wut (cattle camp), countless herds of animals with majestic lyre-shaped horns stretch as far as the eye can see. Young Dinka men and women spend their time surrounded by their beasts, living in perfect harmony with them.” (Source: CarolBeckwith-Angelafisher.com)

Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher are photographers who have devoted their careers to documenting the lives and cultures of the indigenous people of Africa. In their words, “[We have traveled] across 270,000 miles and through remote corners of 40 countries in exploration of more than 150 African cultures.

“In the process, this team of world-renowned photographers has produced 14 widely acclaimed books and made four films about traditional Africa. They have been granted unprecedented access to African tribal rites and rituals and continue to be honored worldwide for their powerful photographs documenting the traditional ceremonies of cultures thousands of years old. As an intrepid team of explorers, they are committed to preserving sacred tribal ceremonies and African cultural traditions all too vulnerable to the trends of modernity.”

![Photo by Carol Beckwith & Angela Fisher: “A Dinka boy from South Sudan lavishes endless care and affection on his animals, which he considers part of the family. He is named after his favoured ox, his Namesake Ox, in the hopes [that] he will mature with the same strength and beauty. He believes that he and his Namesake Ox are one. In the future, this animal will accompany him everywhere, even when he is courting young girls.” (Source: CarolBeckwith-Angelafisher.com)](https://cdn.face2faceafrica.com/www/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/dinka2.jpg)

Photo by Carol Beckwith & Angela Fisher: “A Dinka boy from South Sudan lavishes endless care and affection on his animals, which he considers part of the family. He is named after his favoured ox, his Namesake Ox, in the hopes [that] he will mature with the same strength and beauty. He believes that he and his Namesake Ox are one. In the future, this animal will accompany him everywhere, even when he is courting young girls.” (Source: CarolBeckwith-Angelafisher.com)

SEE ALSO: Our Culture: Body Scarification in Africa

Among some of the opinions shared in the article regarding the photographs of the Dinka people of South Sudan, Osob Mohamud replied:

I can’t deny these photos are beautiful, and they draw me in. But it seems they are there for rapacious consumption and not really for the ostensible reason of “learning about the Dinka.” Images like these just deepen the misunderstanding and “otherness” of people who don’t live in our “developed” and privileged context.

Frankly I’m tired of western photographers embedding themselves in “tribes” and showing us pictures of exotic peoples living in their natural habitat. You can’t help feeling that this could easily have been about wildlife.

Others expressed their concern over the selling of the photos, questioning whether the Dinka people were getting anything back, while some asked whether official consent was given. The critiques, however, were not all negative. One commentator, Chris Ejugbo, questioned why we Africans get angry when an “outsider” documents the beauty in our cultures, yet we have not taken the initiative to show ourselves to the world.

With that point in mind, I would like to share my point of view, not just as an African, but also as a South Sudanese hailing from the Dinka ethnic group, particularly addressing the issues of exploitation/consent, nudity, and profits being made from Beckwith & Fishers’ work.

Photo by Carol Beckwith & Angela Fisher: “At an early age, young Dinka boys and girls tend the herds and perform menial tasks around the camp; their duties start early in the morning and end when the sun goes down.” (Source: CarolBeckwith-Angelafisher.com)

On Exploitation, representing the Dinka as “other” or somewhat “subhuman,” and consent:

While the exploitation of Africans, their land, and people, still exist – look at Congo for example — I find these specific claims and the assumption that the Dinka are being presented as the “other” to be absolutely baseless. These photographers are simply using their skills and craft to showcase the real beauty and culture of the nomadic people of the Dinka tribe, and this was beautifully achieved.

Regarding consent, I will quote Deng Dekuek, a Dinka, South Sudanese writer, and political commentator, “I am hesitant to say the photographers or the nature of their work is exploitative. The Dinka are not naïve and would certainly not have been photographed if they did not consent. Anyone who has tried taking a photograph anywhere in South Sudan can attest. One can only assume then, there was consent.”

Moreover, it is important that before we jump to conclusions, we understand the nature of the relationship Beckwith & Fisher must build with the indigenous tribes they document in their works. For them, this is not simply a search for content, but in the words of Beckwith, “We want future generations of Africans to know where they came from and what their grandparents believed. Over 40 percent of what we have recorded no longer exists, a tragic loss, diminishing the richness and diversity of the human panorama. We hope to leave our archive of the cultural heritage of Africa, 40 years in the making, and still ongoing, to future generations who care about who we are as human beings, where we have come from, and where we are heading.”

I fail to see how the notion of “otherness” comes to play, and at the risk of being taken as an insult, I would say that those who see “otherness” in this breathtaking portfolio are viewing these works with a jaded pair of glasses. In my view, the photographs represent the opposite of “otherness.”

They show, in such a captivating and truthful way, a culture that exists, a culture that is part of our society, a culture that we should embrace, and a culture that we should preserve. These photographs, even at complete face value, with no background understanding of the photographers, embrace beauty, as opposed to looking down on it.

Photo by Carol Beckwith & Angela Fisher: “Dry season cattle camps provide an opportunity for young men and women to meet in total freedom. Sexual matters are discussed openly, though behavior is quite innocent. A young woman’s corset is supported by two rigid wires running down the spine and held tightly in place at the front; it will be cut off and removed on the girl’s wedding day.” (Source: CarolBeckwith-Angelafisher.com)

On Nudity:

We must remember that we, as a larger society, have sexualized nudity by attaching a sexual context to it, and for the Dinka people, this western idea of nudity is a foreign concept. Look at a naked picture of singer Rihanna (pictured below) and look at the picture of the lady above.

The difference is needless to mention.

Furthermore, being naked was, in fact, the way of life of early man and still is the way of life of indigenous African people as well as other indigenous people around the world.

Therefore, perhaps our issue with nudity should not be focused on these photographs, but the sexually driven society we have created. By focusing on nudity, we suggest that this aspect of their culture should be suppressed, which is, in actuality, the real issue.

On Monetization:

In the words of Harlan Ellison, “You are not entitled to your opinion. You are entitled to your informed opinion.” A little research will show that Beckwith & Fisher do give back to the people they work with. More so, how they assist is not by “giving the people fish, but by teaching them how to fish,” because they help build schools, clinics, and wells, etc.

Beyond that, though, I do not see how their work is different from an artist who draws a photo and chooses to sell it or a writer who experiences a different culture, writes a book about it, and chooses to sell it. How much they sell it for is at his/her discretion, and rightly so.

“The Dinka cattle camp at sunset in South Sudan, one of the few still existing camps of up to 2,400 head of cattle, transports one in to a lifestyle of harmony and connectedness, an inseparable bonding between nature, animals, and man. We were struck by its beauty, the layers of smoke at sunset, the striking silhouettes of cattle with their

Professor Donald Johanson, who discovered the “Lucy” skeleton in Ethiopia 40 years ago and is a close friend to Beckwith & Fisher, had this to say about their work:

“Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher’s dedication to recording African ceremonies has produced a vitally important photographic record of human creativity that is rapidly vanishing. Their deep personal involvement and compassion for the endless imagination in African tribal diversity has given peoples around the globe an insight in to the sophistication of these cultures not only through their photographs, but also with the informative texts that put the photos into a wider cultural context.

“Anyone who personally knows these two chroniclers of the beauty, sensitivity, and ingenuity that is part of the African majesty will understand Beckwith and Fisher’s deep thoughtfulness to celebrate and not exploit these tribal groups. Nudity is an important element in many African cultures and not considered a form of eroticism or vulgarity. It is the limited sense of cultural relativity among western observers that leads to such notions.”

“Unlike tourists who casually visit African tribal peoples with their own preconceived notions of exploitation, these two photographers bring an understanding and admiration of the artistry that reflects the true nature of the specific beliefs of those who are being photographed.“

With that said, I believe critical thinking is important; however, sometimes searching deep for faults that do not exist is doing an injustice to the beauty that does exist. Credits must therefore be given where they are due. As an African and a Dinka, what I know of my people has been from books and the narratives told by family and friends. These photos bring me closer to home visually, and are not only something I am proud to show the world as a representation of my people, but also a learning experience for myself.

We must be careful, as Africans that in our advocacy for the telling of African narratives by Africans, we do not, in the process, become separatists. We must remember that our issue, in the very first place, is with narratives that function as “broken telephones” and do not represent a holistic view of Africa. These photographs of the Dinka do not tell a distorted tale but instead paint a realistic image, and as such, should be celebrated. Not only as part of the African roots, but as part of human diversity.

Face2Face Africa has reached out to the photographers and will be speaking with them soon on their work with the indigenous people of Africa. Let us know your concerns or any questions you may have, and we shall do our best to relay them.

[advpoll id=”28″ title=”Advanced Poll” width=”270″]