Since its opening in 1932, New York’s most infamous jail, Rikers Island, has been the subject of concern as it’s been characterized by violence, corruption, dangerous conditions, inadequate services, and overcrowding.

Rikers Island, which is set for closure within the next six years, has seen a lot of well-known faces locked up alongside violent felons and common thieves over the years. Hip-hop musicians, including Tupac, DMX and Lil Wayne, have had their time in Rikers Island but it was Kalief Browder’s three years in the jail without trial that was very unfortunate.

The teen, accused of robbery, later committed suicide after leaving the Island ruined from his ordeal in one of the cruelest jails in America.

But even before becoming a prison, Rikers Island was home to criminals and lawbreakers who dealt in an illegal slavery scheme.

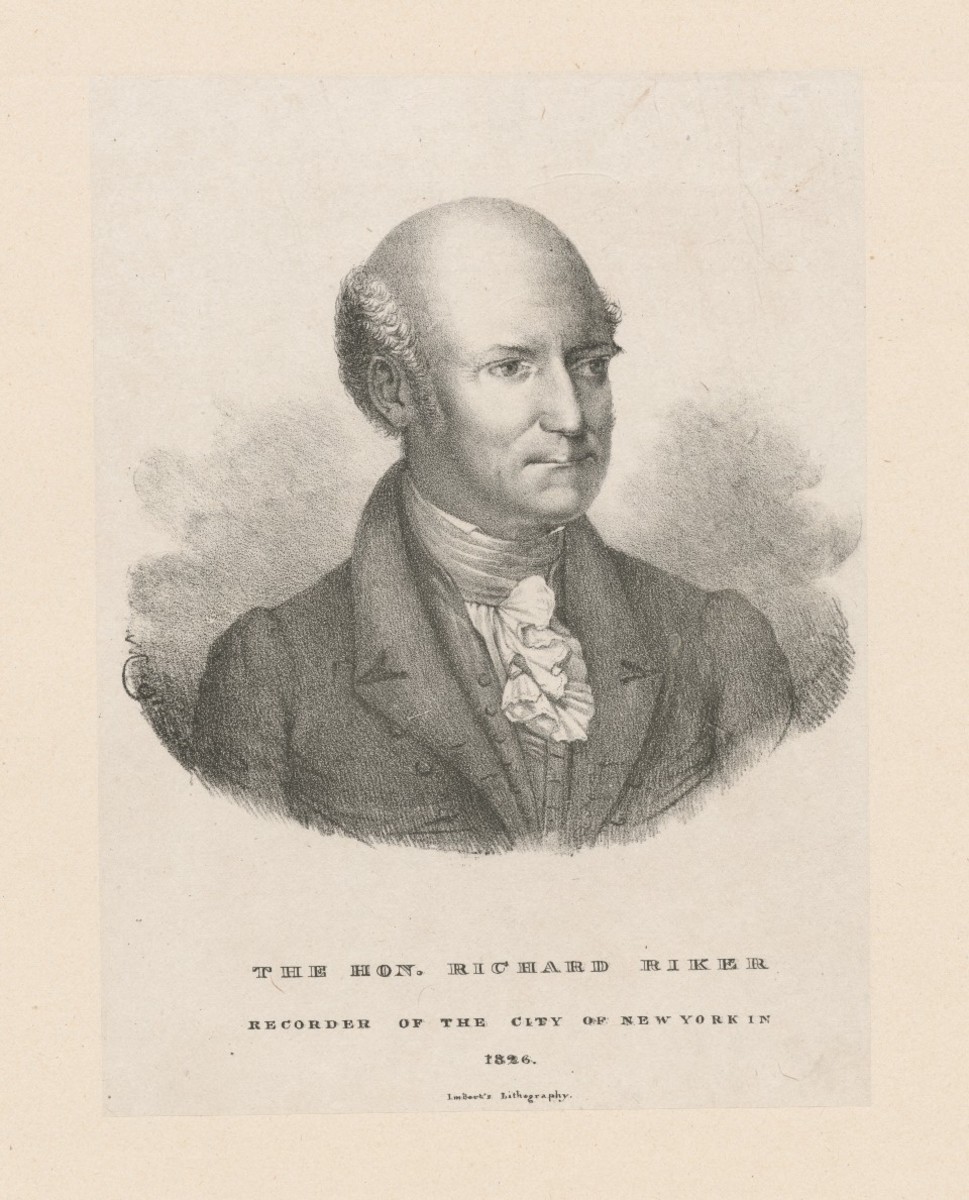

Judge Richard Riker, the owner of the island in the early 1800s, was a descendant of Abraham Riker (otherwise Abraham Rycken), a Dutch immigrant who acquired the land in the 1600s and owned it until selling it to the city in 1884.

In the 1800s while judge Riker owned the island, he became infamous for abusing the Fugitive Slave Act, which was introduced to allow for the capture and return of fugitive slaves in the U.S.

Records show that between 1815 and 1838, Riker used his wealth and power as a presiding judge over New York City’s primary criminal court to ensure that African Americans were quickly “deemed fugitive runaway slaves”, denying them a right to a trial to prove that they were actually free.

A historical abolitionist newspaper, the Emancipator, writes that Riker led a group of officials known as the Kidnapping Club, who “actively conspired” to both send and sell free blacks in New York who were accused of being fugitives, to slaveowners in the South without due process.

“In accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act, members of the club would bring a Black person before Riker, who would quickly issue a certificate of removal before the accused had a chance to bring witnesses to testify that he was actually free,” Elizur Wright Jr.’s 19th-century newsletter “Chronicles of Kidnapping,” cited by history professor Eric Foner, states.

Foner also pointed out one of the moments free blacks were terrorized under Riker:

“[A] North Carolina slaveowner, Dr. Rufus Haywood of Raleigh, staged a midnight raid on the home of one Lockley. Despite protests that he was a free man, Lockley, his wife, and their twelve-year-old daughter were imprisoned as fugitives, and after a series of hearings before Recorder Richard Riker, they were taken south by Haywood.”

In another case cited by the Emancipator, Riker jailed seven-year-old boy Henry Schoot after he was dragged out of his elementary school by a slave-owner. The slaveowner claimed that the boy was the property of his late father and that ownership had passed to his mother. Despite the slave-owner not producing a will to back his claims, Riker sent the boy to jail.

Years after Riker’s injustices, the island, which bears his name, was used as a training ground for Union Army regiments during the Civil War. On July 3, 1884, when the war had ended, city officials bought the island from the last of the Riker family owners for $180,000.

It took another 30 years before officials decided to build a jail on the island to replace Blackwell’s Island Penitentiary.

Today, Rivers Island, with nearly 10,000 beds and about 95 percent of its inmates being black or Latino, has become “synonymous with everything wrong with America’s criminal justice system.”

With its poor conditions and intense violence among both inmates and correctional officers, activists were elated when it was announced last year that the jail complex will be closed and replaced by four smaller jails, one each in Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx.

Earlier, these activists had hoped to have the prison’s name changed in order to detach it from judge Riker’s racist history. Harlem Historical Society Director Jacob Morris, who led a petition to rename the Rikers Island, described the jail complex as “the spider at the center of the web” when it comes to New York City’s history with slavery.

He added: “There’s nothing … socially redeeming about Richard Riker.”