The builders of reborn Ghana wanted the country not only to prosper but to be a beacon to the whole continent. By the time I got there eight years after the regaining of independence, the place was buzzing, and Accra struck you as a place of proud African identity and also as a place of social freedom.

RELATED: Pan-Africanist, Activist Remembers Guyanese Support of Angola

C.L.R. James, a Trinidadian world figure from whom I still learn much, would credit a lot of the social advances to his fellow Trinidadian George Padmore. Breaking with Joseph Stalin over the treatment of the colonial freedom movement in the face of the threat German fascism, Padmore left a high-international position and decided to place his talents at Ghana’s disposal.

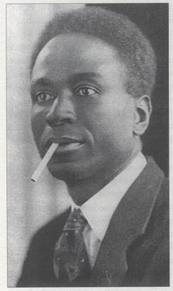

I mention the illustrious Padmore (pictured at left) only to say that if he had not been there, talented sons and daughters would not have risen to the task. Padmore had rich experience of how the world worked. As he and Nkrumah deserve, much is written about each of them.

I mention the illustrious Padmore (pictured at left) only to say that if he had not been there, talented sons and daughters would not have risen to the task. Padmore had rich experience of how the world worked. As he and Nkrumah deserve, much is written about each of them.

I saw very little of Ghana beyond Accra and very few tourist sights, but there are a few unforgettable individuals and gatherings of people I experienced.

At the time, a decision was made that the head of the nation should become an institution on equal footing with the imperial figures who had dominated the continent and had gone a long way in replacing traditions as illustrated in the Chinua Achebe novel “Things Fall Apart.”

One Friday at noon, walking in some part of the Kwame Nkrumah Circle (pictured above), I had to stand and work out what was happening. Hundreds of people — many wearing robe-like clothing — stopped in their tracks and fell toward the ground.

It struck me that for all the visible oneness of the people, there were people of various faiths claiming the same space in the same city.

I had come from a country with a significant minority of Muslims. And even though a Muslim became a minister of government for the first time in Guyana at that time, I would never see such a scene in a city or even in a village or plantation.

In other places, prayer was a matter for the home or the Mosque, but Ghana was different.

Though this is a seemingly idle recollection, this scene has meaning for other parts of Africa today: These good old days are gone, and while every faith has its fanatics, all can look back on Accra in 1965, where a visitor saw a people not dominant in the State proclaiming their faith and doing acts of worship in the Kwame Nkrumah Circle with the understanding of their fellow citizens.

There was also a statue of Kwame Nkrumah with his right arm raised (similar to the one pictured at the top). The late-novelist and poet Neville Dawes, who had Jamaican parents but was born in Nigeria, and his wife, Cho Cho Dawes, said that their son would look at it and say, “Kwame is saying, ‘Stop!'”

There were symbols adopted boldly and lovingly from Marcus Garvey in Ghana.

Two Jamaicans were recognized as vital to Ghana’s reconstruction. Most people have heard of the Black Star Line, a steamship company owned by Black shareholders founded by Garvey and the United Negro Improvement Association (pictured above) as a part of the back-to-Africa movement. To mark that superhuman effort, Nkrumah saw to it that Ghana’s shipping corporation was also called “The Black Star Line….”

RELATED: Pan-Africanist, Activist Remembers Ghana’s & Guyana’s Independence