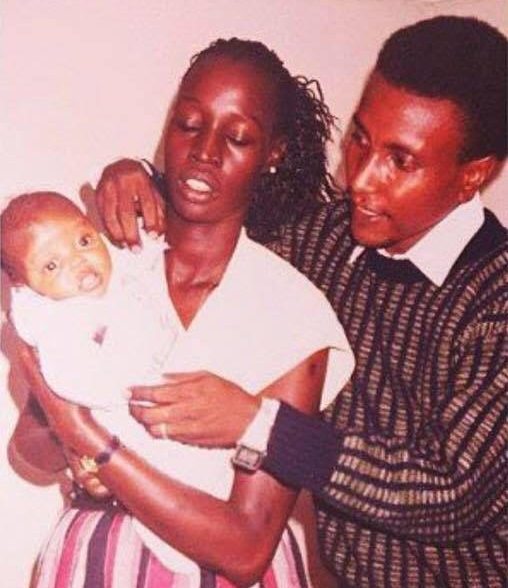

I was born and raised in Kenya to a beautiful tall, slim and dark Dinka woman from South Sudan who walked miles from Sudan to Ethiopia in her teens to join the Sudans People Liberation Movement (SPLM). It is worthy to note that following the secession of South Sudan, SPLM was split into two divisions and SPLM-North continued the rebellion against the current Sudanese government, having endured an unrelenting fight for freedom and justice last few decades.

My father, a Ja’ali man from North Sudan, protested against the same injustices in the streets of Khartoum in his youth, just like the young men I saw in all the videos of the current revolution, joining the SPLA/M movement too, later SPLM/N, continuing to fight for the marginalised people of Sudan, particularly those in forgotten areas like the Blue Nile region.

As a result, I have been politically aware growing up, not least, from books my father would give me or the stories my mother would tell me; the conversations my uncles and aunts would have, even when just recounting tales, would almost always be tied into a political event at the time of the civil war between North and South Sudan.

I understood why we were refugees in Kenya and why there were tensions between the North and South of Sudan. In my household however, there was a harmonic existence of the two and a freedom of belief – my mother is a Christian and my father a Muslim. When it came to the two sides of the family, we were all one people who believed in one God.

For years, before the separation of South Sudan in 2011, Sudanese spoke of the New Sudan vision; a vision pioneered and pushed forth by great men like Dr John Garang De Mabior, one that would unite all Sudanese, giving each their full rights as equal citizens, regardless of ethnic background or social standing.

The New Sudan vision also emphasized on the need to “bring cities to towns”. This would be achieved by not focusing resources and power in the centers only, but equally distributing them in the peripheries as well. It is this vision that inspired men like my father to join the SPLM/A to fight for, advocate and ultimately build this New Sudan, collectively.

Despite violent attempts by the military council (TMC) forces to disperse peaceful protesters since the current demonstrations began six months ago, and the attempts to hide evidence of crime by digging mass graves, shutting down the internet, or stopping organization by cutting off communication networks, the weeks leading up to the June 3rd massacre sparked real conversations on the issues facing Sudan.

It was the first time, we had a glimpse of what the New Sudan vision would have looked like, had we not allowed the government to divide this great nation with their political Islamic agenda, but it was still a beautiful sight nonetheless.

The nation had come together from all corners, putting up peaceful resistance in the big and small towns alike and in one clear voice, demanding the fall of the regime. Although Bashir had been forced to step down on April 6th and Ibn Ouf who took over, was forced to step down a day later by the Sudanese people who did not stop revolting, the system remains the same and only wears a different face; a murderous one allied with and part of the Bashir regime that committed the Darfur genocide and other atrocities across the country over the years, not least against South Sudanese.

Thus, it came as no surprise when bodies of our families in Khartoum were being thrown into the Nile both alive and dead. This knowledge, however, did not make the pain any lighter. What is happening in Sudan is not new – it has been happening to South Sudanese, the people of Darfur who in the last couple of days TMC has turned attention back to and are being massacred.

It has been happening to the people of Nuba Mountains who the government bombs at anytime, denying humanitarian assistance for years and have become accustomed to living in caves on the mountains and jumping into holes whenever they hear the sound of antinov bomber planes approaching from the distance.

Perhaps the only difference is that this time, thanks to citizen journalism and the will of a resilient people, we saw the finish line. We were at the finish line. It was clear. The people were winning. And in just one moment, at 5:30am on June 3rd that finish line was drawn further, dignity was snatched, women were raped in broad daylight as their underwears hang as trophies. as well as men if they dared speak up for the women. Mercilessly, regardless of place – a 6 year old was gang raped by 10 men in a mosque.

This moment broke us to the core. Seeing new images pop up ever minute of heads blown out or literally seeing videos of beating hearts in open chests can take a toll on your mental health. I could only imagine what those on ground must be feeling. I believe I speak for most Sudanese in the diaspora, and at home, when I say the past few months have been an emotional rollercoaster that no schooling ever prepared us for.

We have laughed, cried, been inspired, angered or felt hopeless altogether only to regain this hope the next minute. Sometimes these emotions have been somewhat of a cocktail, a weight that both angers and inspires. We have been angered by how disposable the lives of our brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, children, the old and young alike, Sudanese men and women, have been back home.

Yet, we have been inspired by the beauty in the collective unity we had never seen before, given most of us have only known a broken Sudan and this one dictatorial system since birth. This unity of the nation was symbolised by the gathering in Khartoum at the sit-in area outside the Military Headquarters, the same place now etched into our hearts and minds as a memorial ground of all the people beaten, shot, burnt alive and mass-raped while peacefully demanding their rights. A people whose only weapons were their index and middle fingers raised up in resistance in loud melodic voices chanting “freedom, peace and equality”.

Credit: @eimanpaintings (Instagram)

Sudanese were cleaning dirty streets corners, filling the walls up with art and creating open mic spaces from spaces that previously carried the stench of rubbish.

We were not just changing the system; we were cleaning their mess. I even heard that homeless children were being taught to read and write by those who could. Today, the faces of some of our Matyrs are on the walls. They remind us of the moment Sudanese had a taste from the cups of freedom, the beauty that was birthed from it, the music, the art, the love- it is something we cannot forget. They remind us we have to fight on, until this nation is free and back to its rightful hands; THE PEOPLES.

I have really struggled to write about the Sudanese Revolution. I mean, how do you start writing about watching your nation come alight both in spirit and in fire? How do you begin to relay the pain of a father forced to watch his wife and daughter abused or vice-versa? How do you write about the feeling of helplessness when you hear of how your friends or family were brutalised, the traumas they now live with, that they cannot even fully recount what happened? How do you write an eloquent piece on tragedy? What do you write that can help? And how do you even write about a country whose history is too complex to shrink down into an article? What do you write about and what do you not write about? What is too important to leave out or too insignificant to leave in? Who do you blame for the current crisis in Sudan? AU, EU, US, Russia, China, Arab States?

As someone who has tried to raise awareness of Sudan, it is beautiful to see the world stand in solidarity and the #BlueForSudan spread like wildfire. A movement inspired by Mattar’s favourite colour, a young man who was shot trying to protect two women from security forces, which now symbolises the martyrs of this revolution.

However, I have also had to ask myself, what kind of help does Sudan need from the rest of the world and who are my efforts really helping? For example, is it the Sudanese people or those with vested interest in Sudan? A lot of times situations like this have been used by others as opportunities to cripple nations further or to plunder resources. There is no doubt if the Sudanese Revolution was just the people against the government and the government was not being supported and funded by external forces, the revolution would have been won by the people.

It is difficult to consolidate the convoluted history and current situation of Sudan in one article hence the Sudan Revolution Series – a series covering various aspects of the current revolution, more so in context of South Sudan and Afrika at large, speaking to different voices present and active on the issue, particularly the young voices who represent the aspirations of the nation and the continent.

Stay tuned for the second installment…