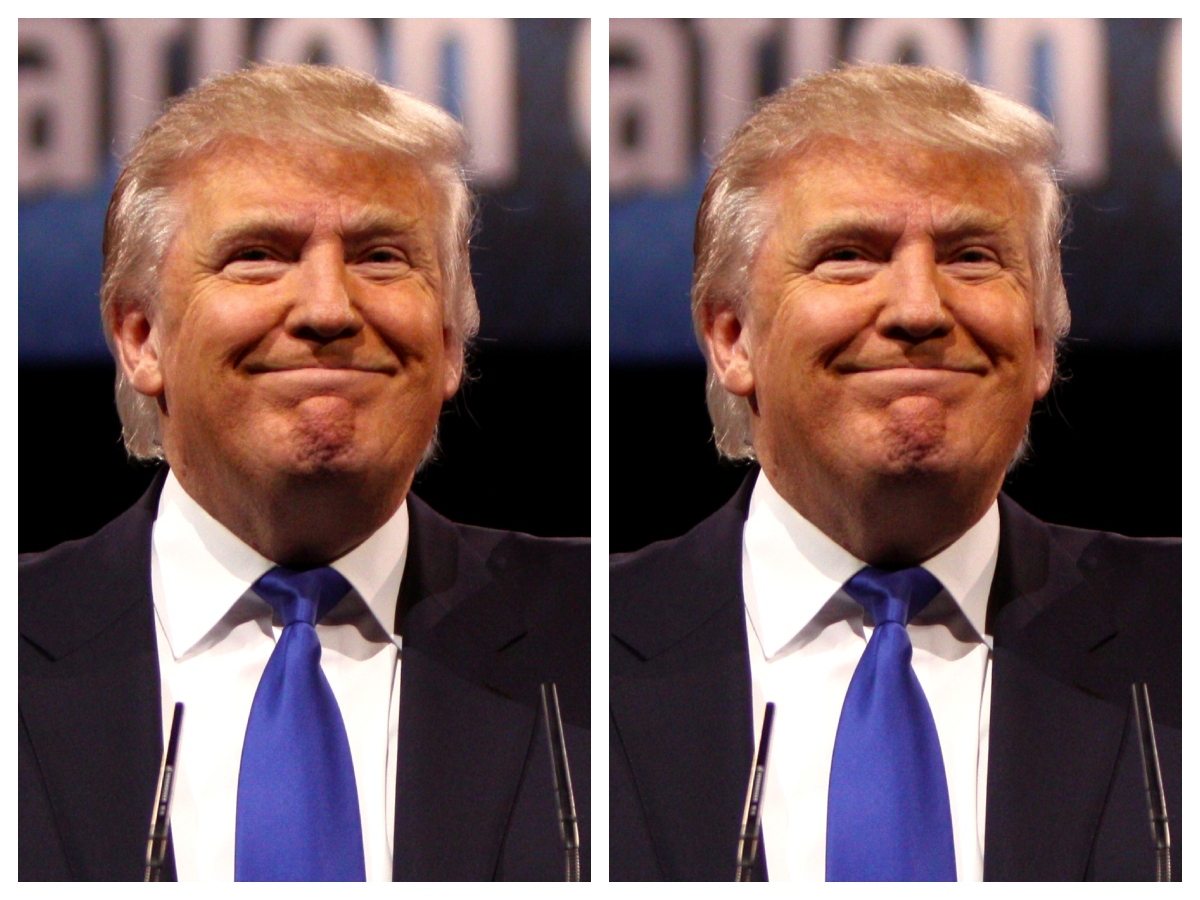

The Trump administration is taking a hard line on the nation’s largest food aid program, claiming that fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is rampant and costly. Officials are pushing for stricter enforcement, highlighting abuses ranging from individual recipients to organized criminal networks and complicit retailers.

“We know there are instances of fraud committed by our friends and neighbors, but also transnational crime rings,” said Jennifer Tiller, a senior advisor to U.S. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins.

Administration officials say SNAP fraud is a growing concern, but experts caution that the full extent remains unclear. Some scholars note that while fraud exists, the actual amount may be far smaller than official estimates suggest.

“If you’re spending $100 billion on anything, you’re going to have some leakage,” said Christopher Bosso, a Northeastern University professor of public policy and politics who has studied SNAP extensively.

The program serves roughly 42 million Americans, about one in eight, with average monthly benefits of $190 per person. Of the $100 billion spent annually, $94 billion in funds benefits, while the remainder covers administrative costs. SNAP recipient numbers closely align with U.S. poverty figures, whether measured by the traditional 36 million or the more nuanced 43 million metric.

Recipients must report income and household information every four to six months and undergo full recertification at least once a year.

As part of its anti-fraud push, the USDA has requested that states turn over detailed data on SNAP recipients, including Social Security numbers, birthdates, and immigration status. Republican-led states and North Carolina have complied, while many Democratic-led states are challenging the request in court, citing privacy concerns.

From the records shared so far, the USDA identified 186,000 deceased individuals, around 1% of participants in those states, still receiving benefits, and about 500,000 people, roughly 2.7%, receiving benefits in more than one jurisdiction. Detailed breakdowns of alleged fraud and what portion of benefits were actually used remain undisclosed.

The USDA has estimated that nationwide, undetected errors and fraud could total $9 billion annually. Democratic-led states counter that existing state systems already monitor misuse, and the USDA has not fully explained its methodology.

READ ALSO: Trump administration targets SNAP management funds in fight over state records

Fraud takes multiple forms. Benefits loaded onto EBT cards can be stolen through skimmers, cloned for fictitious recipients, or used in organized schemes. A Romanian man living in the U.S. illegally pleaded guilty last year to skimming over 36,000 cards in California. Meanwhile, a USDA employee admitted accepting bribes for providing registration numbers for illegally placed EBT card readers in New York, with more than $30 million passing through the terminals.

Other cases include individuals in Ohio accused of using stolen benefits to purchase energy drinks and candy for resale. Mark Haskins, a former USDA special investigations unit chief, noted that retailers also sometimes participate in fraudulent schemes. Starting Jan. 1, several states will prohibit SNAP use for certain junk foods.

Haskins added that some legitimate recipients manipulate purchases or sell their benefit cards, and he believes these smaller-scale abuses may be more costly than organized crime operations. Haskins and Haywood Talcove, CEO of LexisNexis Risk Solutions Government, contend that actual fraud losses likely exceed the USDA’s $9 billion figure.

“The system is corrupt. It doesn’t need a fix here and there, it needs a complete overhaul,” Haskins said in an AP report, advocating for fewer retailers in the SNAP network and mandatory reapplications for participants, even if it creates additional hurdles.

The USDA last published a SNAP fraud report in 2021, covering 2015 to 2017, finding that 1.6% of benefits were stolen. Between October 2022 and December 2024, $323 million in stolen benefits, roughly 24 cents per $100 in benefits, was replaced, though this is believed to undercount the true losses.

Many experts argue that while fraud exists, it is far from the massive problem the USDA portrays. Dartmouth economist Patricia Anderson noted that the potential payoff for fraud is limited unless organized crime targets EBT cards or fabricates recipients.

SNAP users like Jamal Brown of Camden, New Jersey, see fraud and administrative errors as personal frustrations. Brown has had benefits stolen by skimmers, witnessed others sell benefits for cash, and faced cutoffs when recertification interviews were mishandled.

READ ALSO: Inside the Trump administration’s deportation push tearing U.S. families apart

“It’s always something that goes wrong,” he said, “unfortunately.”