It is well known that Anna Maria Vassa, the eldest daughter of Black British abolitionist Olaudah Equiano, died on July 31, 1797, and was buried in Chesterton. However, the exact site of her grave had long been forgotten.

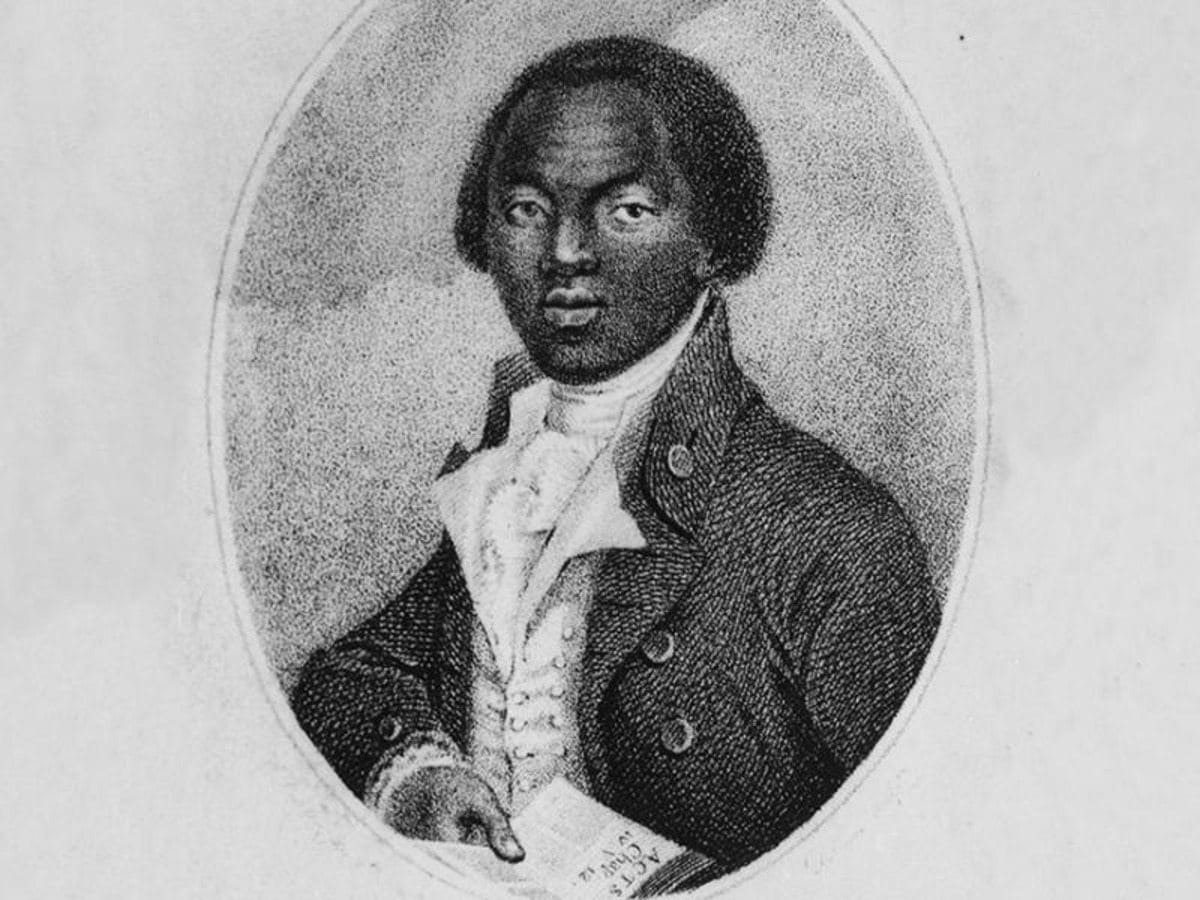

It recently emerged that an A-level student found the lost grave of Equiano’s daughter, Anna Maria. Writer, abolitionist, and former slave Equiano was responsible for writing one of the earliest accounts of the intercontinental slave trade and became a highly visible proponent of the British slavery abolitionist movement.

Equiano’s exact birth date is not known, but most historians agree that he was born around 1745 in the Benin Empire of pre-colonial Africa, which is now known as Nigeria. As a boy, according to Equiano’s account, he was kidnapped by slavers at 11 years of age. He would serve many enslavers before being subsequently trained in Great Britain as a seaman and learned to read and write. Equiano converted to Christianity in 1759 and was later baptized as a protestant.

He eventually escaped slavery to become a celebrated author and campaigner in Georgian England. His memoir, “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African”, was a bestseller.

When his book tour brought him to Cambridgeshire, he eventually married there and had two children with Susannah Cullen, an Englishwoman from Ely. Instead of moving to London, the couple settled in Soham, probably within the parish bounds of St Andrew’s parish church, where they felt safe from violence happening back home that was targeting reformers.

Sadly, their first daughter, Anna Maria Vassa, died when she was three and the exact location of her grave was lost.

However, Prof Victoria Avery, of the Fitzwilliam Museum, recently found a lead to the grave’s location. Avery had gone to Cambridge’s Magdalene College archive in 2021 to research a signed Equiano letter when she found overlooked research by Cathy O’Neill.

O’Neill, while doing her A-levels in 1977, had found and photographed what may be the location of Anna Maria’s plot in the churchyard of St Andrew’s, in the Chesterton area of Cambridge.

During her work in October with independent researcher Dawnanna Kreeger on an article about Equiano’s Cambridgeshire family for Women’s History Review, Avery was finally able to bring the issue to a usually successful conclusion. With the help of the vicar of St Andrew’s, the Rev Dr Philip Lockley, Avery confirmed that a stone text that has been gradually worn away read “AMV – 1797”. She confirmed it as Anna Maria’s footstone, thanks to O’Neill’s earlier research, as reported by the Guardian.

“In the moment of discovery there was a deep sense of her being found,” Lockley said.

Lockley’s church has had an annual day since the 1990s in remembrance of Anna Maria and her father. In October 2022, a community project that began on the back of the Black Lives Matter movement renamed a bridge after Equiano.

St Andrew’s is now working to install a stained glass window commemorating Equiano’s family to further connect with the community.

“People connect with it in a way you wouldn’t necessarily know as a piece of history,” Lockley said. “We’re such an area where new people are coming all the time but are really interested to hear of these long roots and connections into Black history and it being a part of Cambridge’s links to the campaign against the slave trade and enslavement.”

Even though the location of Anna Maria’s grave remained unknown for decades, an epitaph on St Andrew’s north wall dating back to the time of her death celebrates her and describes how her father was enslaved before getting married to her mother.

The epitaph was written by Equiano’s friend, the abolitionist Edward Ind, who was one of Anna Maria’s guardians. This is the inscription on the stone:

Near this Place lies Interred

ANNA MARIA VASSA

Daughter of GUSTAVUS VASSA the AFRICAN.

She died July 21, 1797.

Aged 4 Years [sic].

Should simple village rhymes attract thine eye,

Stranger, as thoughtfully thou passest by,

Know that there lies beside this humble stone,

A child of colour haply not thine own.

Her father born of Afric’s Sun-burnt race,

Torn from his native fields, ah, foul disgrace:

Through various toils, at length to Britain came,

Espous’d, so Heaven ordain’d, an English dame.

And follow’d Christ: their hope two infants dear,

But one, a hapless Orphan, slumbers here.

To bury her the village children came,

And dropp’d choice flowers, and lisp’d her early fame:

And some that lov’d her most, as if unblest,

Bedew’d with tears the white wreath on their breast;

But she is gone and dwells in that abode,

Where some of every clime shall joy in God.

Avery also found in her research that, “Within Cambridge, Ely, Soham, there were groups of like-minded men and women who loved him [Equaino], believed in the [abolitionist] cause, supported him, his marriage and provided a supportive environment for the young Vassa family. The great tragedy is that Susannah dies so shortly after the birth of their second daughter, Equiano dies just over a year after that. Anna Maria dies shortly after.”

Equiano’s other daughter, Joanna, who survived to adulthood and inherited his considerable savings, is buried in Stoke Newington.

Equiano was a vocal opponent of slavery, adopting the once-widely-held stance of Quakers who saw the act as an affront to humanity. Encouraged by Quakers to tell his story by way of the financial and social investment, Equiano would eventually publish his book in 1789, and it made him a prominent pioneer of the abolitionist movement.

Equiano’s book inspired other similar narratives from former slaves. Equiano was also a vaunted figure of the poor Black community in London and served to assist African and Asian immigrants in the country.