The story of the last illegal shipment of 110 slaves to the United States from the Kingdom of Dahomey (present-day Benin) in 1860 is widely known, but the account of the survivors was unavailable until May 8, 2018.

Thanks to a resurfaced 1931 interview with the last survivor of the slave ship Clotilde, Cudjo Lewis, which was published after 87 years by American publishers HarperCollins.

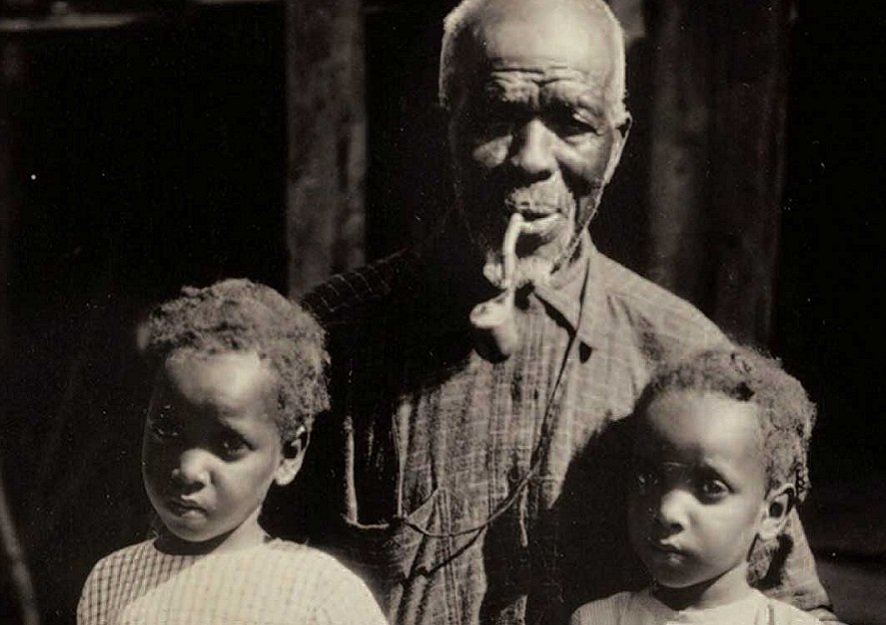

Cudjo Lewis

95-year-old Lewis told his story to African American writer Zora Neale Hurston, who was a known Harlem Renaissance figure and gained popularity for the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

However, the manuscript including other works of hers was rejected by publishers following a public fallout. She was accused of molesting a 10-year-old boy.

Hurston was later exonerated because she was out of the country when the crime was committed; however, her vindication came too late as she had died alone and poor in 1960. She was also buried in an unmarked grave in Fort Pierce, Florida.

Zora Neale Hurston

Barracoon, The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” is one of Hurston’s unpublished non-fiction books which she wrote after she visited Plateau, Alabama, in 1927 to interview Cudjo Lewis.

He gave a firsthand account of the raid that led to his capture and enslavement, over 50 years after the transatlantic slave trade was outlawed in the United States. Hurston documented Lewis’s story in his dialect, just as he told it.

Lewis was born as Kossola or Oluale Kossola in what is now known as Benin around the 1840s. His father was named Oluwale and his mother Fondlolu. He had five siblings and twelve half-siblings from his father’s other two wives.

He was taken prisoner in 1860 by the Dahomey army as part of a slave raid and was sent to the slave port of Ouidah along with other captives. They were sold to Captain William Foster of the Clotilde, a ship based in Mobile, Alabama, and owned by businessman Timothy Meaher.

The owner is reported to have bet a friend that he could smuggle in a group of slaves from Africa aboard the ship.

About 120 of them were bundled onto the ship and brought to Alabama despite the outlaw of slave trade in 1807. To avoid detection, they snuck the slaves into Alabama at night and hid them in a swamp for several days.

“We very sorry to be parted from one ’nother. We seventy days cross de water from de Affica soil, and now dey part us from one ’nother. Derefore we cry. Our grief so heavy look lak we cain stand it. I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama,” Lewis told Hurston.

They burned the 86-foot sailboat on the banks of the Mobile-Tensaw Delta to hide their crime following a tip-off to the authorities of their activities. They were cleared of charges of illegal possession of captives as the slaves and evidence were not found.

The remains of the boat were reported to have been discovered by a journalist in January 2018.

The incident happened months before the 1861 civil war and Lewis, together with the other slaves, were dispersed and hidden by Meaher, his family and associates. Lewis was bought by James Meaher, brother of the businessman, and he worked as a deckhand on a steamer.

“We doan know why we be bring ’way from our country to work lak dis. Everybody lookee at us strange. We want to talk wid de udder colored folkses but dey doan know whut we say,” he told Hurston.

Lewis chose to be called Cudjo, as Kossola was difficult for Meaher to mention. Cudjo is a West African name given to boys born on Monday. Historian Sylviane Diouf believes the surname Lewis was a corruption of his father’s name Oluwale.

He worked at the Meaher shipyard with other slaves through to the end of the Civil War in 1865 when the confederate army surrendered. Lewis said they didn’t know about the war and a few days after it was over, a group of Union soldiers stopped by where they were working and told them they were free.

He told Hurston about his frustration following his discovery that the promise of “forty acres and a mule” to enslaved Africans after the emancipation was not fulfilled by the government.

The group worked in lumber mills and sold produce to raise money to be able to return to Africa, yet they were unsuccessful. An attempt to get their former captor to offer them land also proved futile.

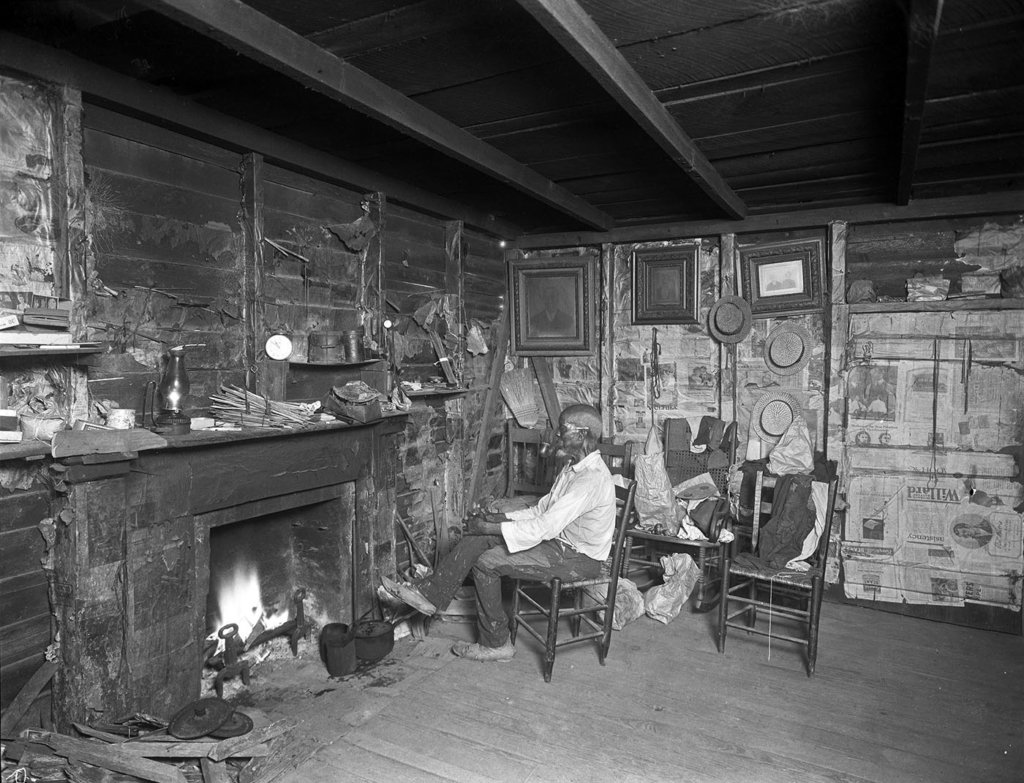

They continued to raise money and later in 1872, Lewis and a group of 31 other freed people bought a land near the state capital Mobile. Lewis bought about two acres of land for $100 in the Plateau area which they called Africatown.

The group developed Africatown into a community of people with a shared African background. They appointed leaders and built a church, a school, and a cemetery.

The freed slaves at Africatown

Historian Diouf wrote that: “Black towns were safe havens from racism, but African Town was a refuge from Americans.”

Lewis converted to Christianity in 1869 and joined a Baptist church. He was married to another Clotilde survivor, Abile (Celia) in 1880 and they had six children. He outlived his family as his wife died in 1905.

He worked as a farmer and labourer until 1902 when he was injured in an accident. He then worked as a sexton in the Baptist Church.

As the last slave ship survivor, Cudjo Lewis gained national fame after rounds of interviews and stories were written about him. He died on July 17, 1935, and was buried at the Plateau Cemetery in Africatown.

Grave of Cudjo Lewis