U.S. lawmakers wore Ghana’s hallmark fabric, kente, at the U.S. President Donald Trump’s first State of the Union address, to stage a silent protest against his infamous “shithole” comments.

Members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) who sat together in the chamber and were largely unmoved during the president’s account of his successful first year in office, say they wore the attire to present “a large and unified force visually”.

Democratic Rep. Al Green of Texas who spoke with the Daily Mail said, “I’m wearing this to show my solidarity with the continent of Africa, and especially with those countries that the president demeaned, defamed, by indicating they were s-hole or s-house countries. I’m wearing it to show that solidarity, and to let the president know that I disapprove of his statements and his behavior.”

Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va tweeted the following, “Wearing kente cloth to the #SOTU with my fellow @OfficialCBC Members to stand in solidarity with people from you-know-what countries”.

Wearing kente cloth to the #SOTU with my fellow @OfficialCBC Members to stand in solidarity with people from you-know-what countries pic.twitter.com/Wc8FIcUKIG

— Rep. Bobby Scott (@BobbyScott) January 31, 2018

President Trump is reported to have dismissed Haiti, El Salvador, and African nations as “shithole countries” whose inhabitants are not desirable immigrants, to more “hardworking” immigrants from Norway. Although the President has denied making such remarks, saying he only “used tough language”, he has been condemned by many.

The Politics of Kente

The use of kente as a visual protest and sign of identification and unity with Africa has a long history.

Although the fabric hails from Ghana, the cloth has come to not only represent the country, but Africa and the Black Diaspora. The Asante and Ewe ethnic groups in Ghana have been hand weaving these silk and cotton fabric into symbolic bright patterns and shapes for centuries. Once designated for chiefs and leaders, Ghanaians now wear kente to weddings and other special occasions.

Ghana’s president Nana Akufo Addo wearing kente during his inauguration in January 2017

Kente & The Diaspora: Kente became popular among black Americans in the 1960s when the independence movement in Africa coincided with the civil rights and black power movement in America, causing a crossover of ideologies, culture – food, clothes, music, and of course people.

In fact, when Ghana celebrated its independence in 1957, Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president, donned the fabric in the presence of friend and Civil Rights icon Martin Luther King Jr and other U.S. foreign dignitaries and leaders.

Nkrumah wore kente to the White House in 1958 to meet with then U.S. president Eisenhower.

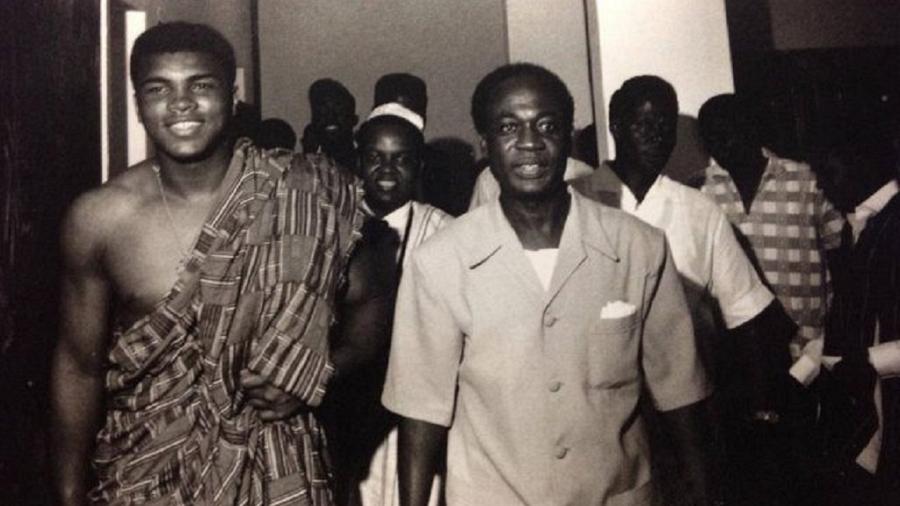

Countless dignitaries, both African and African American, have worn and continue to wear the fabric as a symbol of solidarity and unity. In 1964, Nkrumah presented boxing champion Muhammad Ali with the kente while in Ghana, the first stop of his Pan African tour.

Ghana’s Asante King Otumfuo Osei Tutu II honored the late great South African president, Nelson Mandela with rich Kente cloth and sandals and a framed citation when he conferred him as Okofo, the traditional warrior title. Michael Jackson, the king of pop wore kente when he was crowned honorary King Sani in a ceremony held in the village of Krindjabo, Ivory Coast.

Today, kente stoles, a strip of the cloth, are worn by many African-Americans during their graduation as a symbol of cultural identification and unity.

Yet, as the Global Post reports, the move to wear the fabric has not been without contention, especially with U.S. law. A Washington, D.C. judge removed a lawyer from a case in 1992 because the lawyer refused to remove a kente stole worn over his suit. In 1998, a Colorado judge upheld a high school’s ban on kente stoles over graduation robes, ruling public schools shouldn’t have “racial identification”.

The decision by members of the CBC to wear Kente, knowing its historical and political implications, therefore is not a fashion statement. It has deep political and historical implications as a firm show of solidarity with the Pan-African cause, especially as African immigrants in the U.S. also wrestle with new regulations around their statuses including “dreamers”.