Vivien Thomas, a talented carpenter from Nashville, Tennessee who was born in New Iberia, Louisiana on August 29, 1910, created a technique to fix ‘Blue Baby Syndrome’ via heart surgery.

In 1929, he enrolled as a premedical student at Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial College after working as a hospital attendant to raise money for college.

Unfortunately, the bank crashed that year and he lost his life’s savings and as a result, he was compelled to drop out of school.

This young black man had no formal medical training, but developed techniques and tools that had led to what we know today as heart surgery.

Considered the father of modern cardiac surgery, Dr. Alfred Blalock reportedly hired Thomas as a laboratory assistant in 1930 while at Vanderbilt University and together they conducted experiments that focused on the treatment of hemorrhagic shock.

They developed a number of novel animal models. Eleven years later, Blalock was recruited back to Johns Hopkins, and he requested that Thomas accompany him, and again they re-established a surgical lab in Baltimore.

At the time, the only other black employees at the Johns Hopkins Hospital were janitors. According to Dr. Denton Cooley, who was then beginning work on his medical degree, “People stopped and stared at Thomas, flying down corridors in his white lab coat. Visitors’ eyes widened at the sight of a black man running the lab. But ultimately the fact that Thomas was black didn’t matter either. What mattered was that Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas could do historic things together that neither could do alone”.

At Hopkins, Blalock and Thomas along with pediatric cardiologist Helen Taussig, developed a groundbreaking surgical procedure to correct the Tetralogy of Fallot.

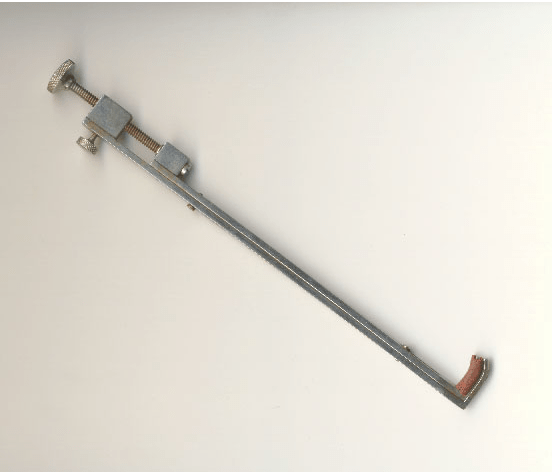

According to reports, Thomas was responsible for perfecting the anastomotic modeling. He taught Blalock the technique and also created the surgical instruments to perform the delicate operation.

In November 1944, the history of medicine was changed forever when the first surgery to correct the Tetralogy of Fallot on a baby was successfully performed by Blalock, aided by Thomas.

Cooley, in a report, recounted the tension in the operating room that November morning in 1944 as Dr. Blalock rebuilt a little girl’s tiny, twisted heart.

“The baby went from blue to pink the minute Dr. Blalock removed the clamps and her arteries began to function and Thomas stood on a little step stool, looking over Dr. Blalock’s right shoulder, answering questions and coaching every move”.

“You see,” explains Cooley, “it was Vivien who had worked it all out in the lab, in the canine heart, long before Dr. Blalock did Eileen, the first Blue Baby. There were no ‘cardiac experts’ then. That was the beginning.”

Thomas went on to train so many surgical residents in his lab at Hopkins, including Drs. Denton Cooley and William Longmire.

As an intern, Dr. Cooley said he saw both Thomas and Blalock devise an operation to save infants born with a heart defect that sends blood past their lungs called “Blue Babies.”

Thomas’ contributions as a surgical technician with such outstanding skill and accomplishment never got acknowledgment until 1976 after Blalock’s death, when Johns Hopkins University awarded him an honorary doctorate.

His legacy has been honoured with the naming of the Vivien Thomas High School Research Program at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

“Vivien Thomas wasn’t a doctor. He wasn’t even a college graduate. He was just so smart, and so skilled, and so much his own man, that it didn’t matter,” noted Cooley.

In 2004, a movie titled “Something the Lord Made” was based on Thomas’ life story.