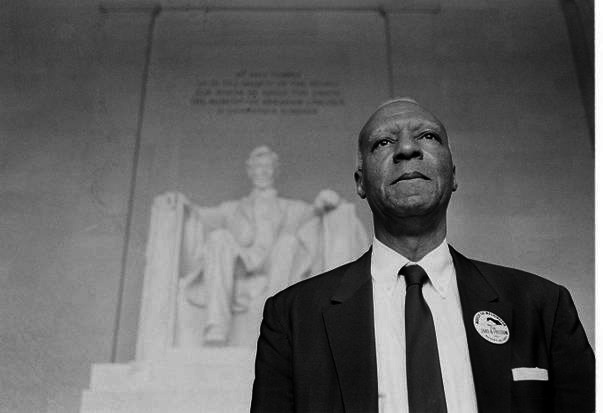

Even though his opponents referred to him as the “most dangerous Negro in America,” Asa Philip Randolph was actually an advocate of nonviolent change.

Described as the most influential black trade unionist in American history, his achievements in peaceful political protests, militant journalism, and black union organizing cannot be overemphasized.

Interestingly, he achieved the above through a nonviolent approach, having believed in the ideals of Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian iconic leader who employed nonviolent resistance in his successful campaign for his country’s independence from Britain.

“I think that perhaps in my work I was distinguished more for my championing of the philosophy and principles of Gandhiism than I was, at times, for trade unionism,” Randolph said in an interview.

And though in his later years he was condemned by some militant civil rights leaders for his nonviolent approach and patience to achieve his goals, Randolph is still widely praised for doing more to seek justice for the poor, minorities and working classes around the world.

Experts say that his ability to lead people and effect change perhaps earned him the title of “the most dangerous Negro in America”.

A son of a minister of the African Methodist-Episcopal Church in Florida, Randolph was born in Crescent City, Fla., on April 15, 1889.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-50440522-ce17a5e19ccc4be282bb78cb0afc71e9.jpg)

He attended Cookman Institute in Jacksonville (now Bethune-Cookman College) where he developed an interest in theatricals.

Dissatisfied with a system that limited jobs for young black people in Florida, Randolph and a friend moved to New York in 1911.

There, from learning public speaking to gaining an interest in radical politics, Randolph established the controversial newspaper, The Messenger.

In circulation from 1917 to 1928, the newspaper, which authorities described as ‘the most dangerous of all the Negro publications’, attracted a huge audience among blacks and middle-class workers.

In 1917 when the paper began publication, the United States was already at war and while leading black intellectuals like W. E. B. DuBois were urging blacks to support the war, Randolph and a colleague, Chandler Owen asked black people to do otherwise.

Both men were arrested and officials investigated their draft status. While Owen was drafted and served six months in a training camp after their release, Randolph was never inducted because the war ended at a time he was supposed to report for that purpose.

Then in 1925, at the age of 36, Randolph was approached by some Harlem porters who complained about the many injustices meted out to them by Pullman Co. on whose cars they worked.

Agreeing to fight on their behalf, Randolph established the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters on August 25, 1925, which became the first African-American labor union with an international charter from the American Federation of Labor.

It will take Randolph and the union more than a decade of fighting before the latter won a collective bargaining agreement in 1937.

At the same time, African-American workers were finding it difficult to acquire defense jobs.

Believing that African Americans could flourish in the United States if they united to end discrimination and segregation, Randolph called for a protest march on Washington in 1941.

This would compel then-President Franklin Roosevelt to establish the Fair Employment Practices Committee, in which Roosevelt claimed: “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

Randolph also founded the League for Nonviolent Civil Disobedience Against Military Segregation which played a huge role in making then-President Harry Truman end segregation in the armed forces.

Despite his many initiatives to improve the lots of black people, many agree that his major achievement was the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

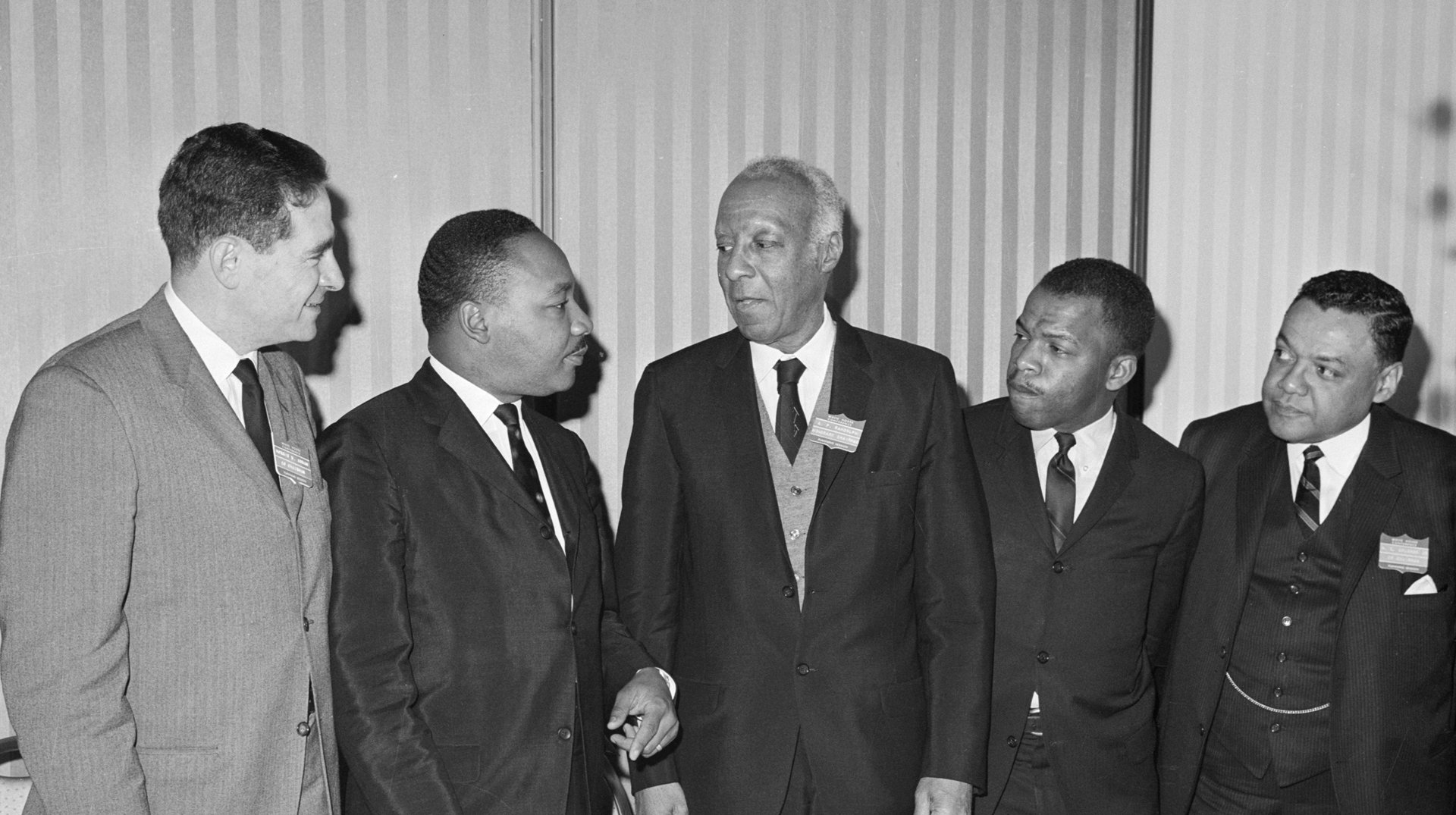

Despite pressure from authorities to cancel the protest, Randolph was able to make progress with the help of other influential black personalities like Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King, Jr. who is remembered for his inspiring “I Have a Dream” speech.

With over 250,000 people in attendance, the march was a turning point in the civil rights movement and influenced the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Essentially, Randolph “helped transform the face of the American nation,” said then-President Carter in 1979 when the former passed away.

In a statement issued by the White House after his death, the president summarized the civil rights leader’s career as one who “helped sweep away longstanding barriers of discrimination and segregation in industry and labor unions, in our schools and armed services, in politics and government.”

“For each new generation of civil rights leaders, he was an inspiration and an example.

“His dignity and integrity, his eloquence, his devotion to nonviolence, and his unshakeable commitment to justice for all helped shape the ideals and spirit of the civil rights movement. . . America will always be a more just, more humane, and more decent nation because A. Philip Randolph lived among us.”