The American justice system has swallowed many innocent souls. It has proven it can eat up, as well as, spit out people at will – many of whom are people of color.

The police, a key agent from whom cases come to the court, have not always been ethical and fair.

Despite glaring inconsistencies, the records show some still march on with the intent to pin a crime on one who is totally faultless, innocent and ignorant of charges being heaped on them.

In 1999, Norman Jewison’s feature film ‘The Hurricane’, starring Denzel Washington shed light on an injustice done a boxer, touching on the accusation, trials and time spent in prison.

Who then was Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter?

Carter born on May 6, 1937 was an Africa-American middleweight boxer, who was wrongfully convicted of murder and later released following a petition of habeas corpus after serving almost 20 years in prison. He would relocate to Canada and become American-Canadian.

Carter, who grew up in Paterson, New Jersey, was arrested and sent to the Jamesburg State Home for Boys at age 12 when he knifed a man he claimed was a pedophile.

“Carter escaped before his six-year term was up and in 1954 joined the Army, where he served in a segregated corps and began training as a boxer. He won two European light-welterweight championships and in 1956 returned to Paterson with the intention of becoming a professional boxer. Almost immediately upon his return, police arrested Carter and forced him to serve the remaining 10 months of his sentence in a state reformatory.” He was discharged in 1956 as unfit for service, after four courts-martial,” according to Biography.

Another prison stint followed in 1957, this time at the Trenton State Maximum-Security prison for purse snatching. He would turn pro in 1961, beginning a startling four-fight winning streak, including two knockouts.

“For his lightning-fast fists, Carter soon earned the nickname “Hurricane” and became one of the top contenders for the world middleweight crown. In December 1963, in a non-title bout, he beat then-welterweight world champion Emile Griffith in a first round KO. Although he lost his one shot at the title, in a 15-round split decision to reigning champion Joey Giardello in December 1964, he was widely regarded as a good bet to win his next title bout.”

Carter was training for his next shot at the world middleweight title (against champion Dick Tiger) in October 1966 when he was arrested for the June 17 triple murder of three white patrons at the Lafayette Bar & Grill in Paterson. Carter and John Artis had been arrested on the night of the crime because they fit an eyewitness description of the killers (“two Negroes in a white car”), but they had been cleared by a grand jury when the one surviving victim failed to identify them as the gunmen.

The prosecutor was adamant even when it emerged the only two eyewitnesses Bello and Bradley were petty criminals involved in a burglary (who were later revealed to have received money and reduced sentences in exchange for their testimony) but it didn’t stop Carter and Artis of being convicted of triple murder and sentenced to three life prison terms on June 29, 1967.

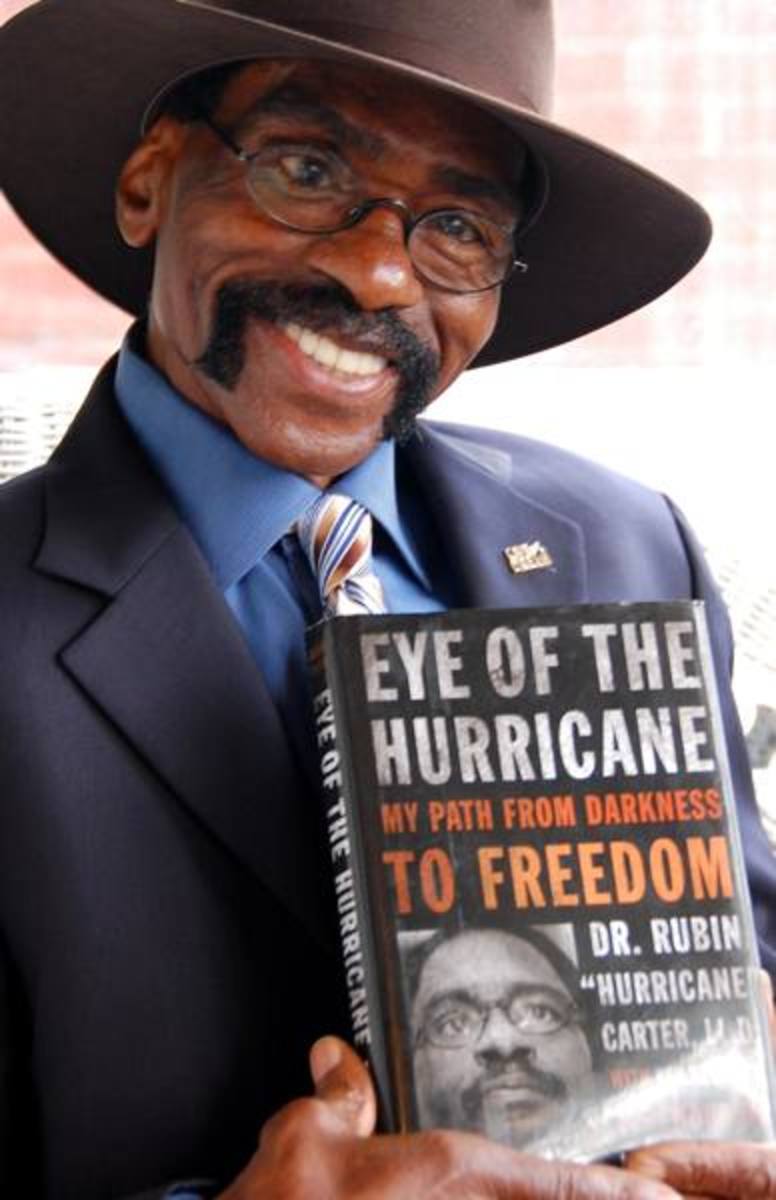

Believing that he had been given a raw deal, Carter channeled his energies at the Trenton State and Rahway State prisons by reading and studying extensively, publishing his autobiography, The 16th Round: From Number 1 Contender to Number 45472, to widespread acclaim in 1974.

Bob Dylan and Muhammad Ali were some of the leading figures to call for Carter’s freedom.

“In late 1974, Bello and Bradley both separately recanted their testimony, revealing that they had lied in order to receive sympathetic treatment from the police. Two years later, after an incriminating tape of a police interview with Bello and Bradley surfaced and The New York Times ran an exposé about the case, the New Jersey State Supreme Court ruled 7-0 to overturn Carter’s and Artis’s convictions. The two men were released on bail, but remained free for only six months — they were convicted once more at a second trial in the fall of 1976, during which Bello again reversed his testimony.”

In 1982, the New Jersey State Supreme Court rejected the appeal for a third trial, affirming the convictions by a 4-3 decision. Carter had demanded his wife Mae Thelma stop visiting. The couple divorced in 1984. The union produced a son and a daughter.

By 1980, Carter had developed a relationship with Lesra Martin, a teenager from a Brooklyn ghetto who had read his autobiography and initiated a correspondence. Martin was living with a group of Canadians who had formed an entrepreneurial commune and had taken on the responsibilities for his education. Before long, Martin’s benefactors, most notably Sam Chaiton, Terry Swinton, and Lisa Peters, developed a strong bond with Carter and began to work for his release.

Their efforts intensified after the summer of 1983, when they began to work in New York with Carter’s legal defense team, including lawyers Myron Beldock and Lewis Steel and constitutional scholar Leon Friedman, to seek a writ of habeas corpus from U.S. District Court Judge H. Lee Sarokin.

On November 7, 1985, Sarokin handed down his decision to free Carter, stating that “The extensive record clearly demonstrates that petitioners’ convictions were predicated upon an appeal to racism rather than reason, and concealment rather than disclosure.” The state continued to appeal Sarokin’s decision — all the way to the United States Supreme Court — until February 1988, when a Passaic County (NJ) state judge formally dismissed the 1966 indictments of Carter and Artis and finally ended the 22-year long saga.

The 48-year-old was freed without bail.

Upon his release, Carter moved to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, into the home of the group that had worked to free him. He worked with Chaiton and Swinton on a book, Lazarus and the Hurricane: The Untold Story of the Freeing of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter published in 1991. He and Peters were married, but the couple separated when Carter moved out of the commune.

The former prizefighter, who was given an honorary championship title belt in 1993 by the World Boxing Council, served as director of the Association in Defense of the Wrongfully Convicted, headquartered in his house in Toronto. He also served as a member of the board of directors of the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta and the Alliance for Prison Justice in Boston.

Carter born in Clifton, New Jersey was the fourth of seven children. The boxing world took notice of his abilities when he defeated a number of middleweight contenders – such as Florentino Fernandez, Holley Mims, Gomeo Brennan and George Benton.

Carter’s boxing record is 27 wins, 12 losses, and one draw in 40 fights, with 19 total knockouts (8 KOs and 11 TKOs). He is an inductee of the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame.

In March 2012, while attending the International Justice Conference in Burswood, Western Australia, Carter revealed that he had terminal prostate cancer. At the time, doctors gave him between three and six months to live. Beginning shortly after that time, John Artis lived with and cared for Carter, and on April 20, 2014, he confirmed that Carter had succumbed to his illness.

He was 76.