During the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 60s, public libraries, expected to be accessible by the general public, were just as segregated as the rest of America.

“The few public libraries in the South that did provide limited services to blacks often subjected them to experiences that were humiliating,” writes Eberhart in 2018.

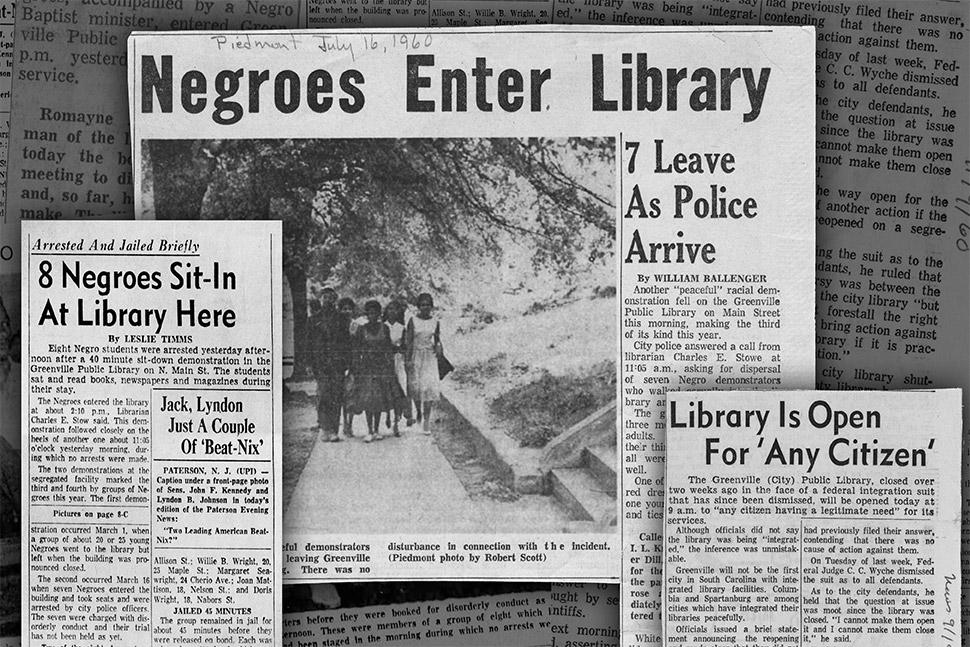

Thus, African Americans would resort to sit-ins and other peaceful protests to fight for equal access to public places, including public libraries. In March 1961, a group of black students, who would later be known as the Tougaloo Nine, became the first Mississippi students to stage a sit-in against segregation when they staged a demonstration at the main public library in the city of Jackson.

A year earlier, on February 1, 1960, students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College had launched the sit-in movement with a protest at a Greensboro lunch counter.

Students from black colleges across the South would follow suit at various public places, including libraries, department stores, lunch counters, among others that denied service to blacks, according to Mississippi Encyclopedia.

During this period, the city of Jackson had an ordinance that barred black people from using the main library and whites from using the George Washington Carver Library, designated for blacks.

Some students of the Tougaloo College in Mississippi, most of whom were members of the Jackson Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), would challenge the system.

On March 27, 1961, nine students, who were also members of the Jackson Youth Council of the NAACP – Meredith Coleman Anding Jr., James Cleo Bradford, Alfred Lee Cook, Geraldine Edwards, Janice Jackson, Joseph Jackson Jr., Albert Earl Lassiter, Evelyn Pierce, and Ethel Sawyer – entered Jackson’s main library and started browsing through the card catalog and later sat down to read.

When the police arrived and asked the students to leave, they refused and were arrested on charges of breach of peace.

Recounting the incident, Geraldine Edwards, who was one of the students arrested, said they had requested books not held by the “coloured” branch of the library and were arrested by the police because they did not belong there.

“I went to the desk very confidently,” she said, “and asked for a specific book. I let her know that I had already done the research and I could not get the book at the black library.”

“We had heard that all our lives. But we felt that we belonged wherever we wanted to be,” she was quoted by American Libraries recently.

Edwards explained that there were actually 16 students who were part of the incident, all of whom had prepared and trained for any kind of protest that may occur.

“The other seven did not go into the library, but they served as lookouts for cars and police and to tell us when the coast was clear. They were just as brave as we were, but we were the ones who got arrested.”

“We went through training based on what we could expect to encounter,” she said. “We knew from the news that we might be subjected to beatings, dogs, billy clubs, even death. We rehearsed getting harassed with vulgar words, taunts, and violent movements to see which of us could hold up under stress. Not everyone could do that.”

“We knew exactly what we were doing and we all looked confident. However, I found out at the 45th anniversary of the read-in that one of the other students had sat down with a book and was reading it upside down.”

“The police were already there, so someone must have tipped them off,” she said. “The media knew we would be there. Others were in charge of contacting the newspapers behind the scenes. We did not want to go in without media coverage as insurance. If they had not been there, the correct news would never have gotten out.”

“After we were arrested, we had no right to call a lawyer,” Edwards indicated. “We were put in individual holding tanks and questioned separately.”

There were reports that civil rights leader Medgar Evers had worked with the Tougaloo students, preparing and training them for the protest, but they told the police upon arrest that they were doing it on their own.

“The police used mind-bending techniques. They wanted to get into our heads, but we wouldn’t let them. They held us for about 30 hours, but it seemed much longer than that,” Edwards recounted.

“Afterwards, the community came out to support us. Some Jackson State University students protested our arrest because we had not hurt anyone and we were just asking for our civil rights.”

“Several students made some comments to the police, and that’s when they released the dogs and were beaten. What we did didn’t really make the national news. It was the violence that happened afterwards,” said Edwards, who has since written a book about her life and details on the Tougaloo Nine, Back to Mississippi (Xlibris, 2011).

Evers would, meanwhile, gather bail for the release of the students. They were ultimately convicted, fined one hundred dollars each, and given thirty days in jail, although that part of the sentence was suspended.

Their actions led to the integration of what is currently the Jackson Metropolitan Library System, and they have been honoured by the college and by the city of Jackson.