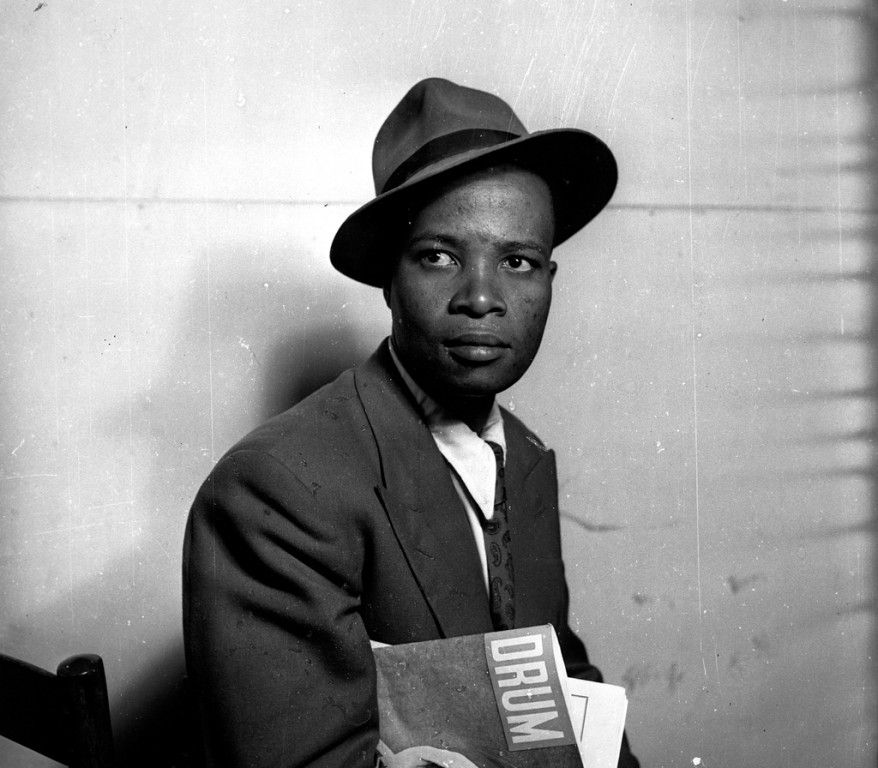

Henry Nxumalo, in the early post-war years, believed that Africa was about to witness great things and that a free and responsible press would facilitate that change.

As such, the man, who would be described as one of South Africa’s best journalists and the “the greatest investigative journalist South Africa has ever produced”, risked his life to expose ills of the apartheid system.

Doing daring investigative work for Drum, an iconic magazine in the 1950s in South Africa, Nxumalo often “donned disguises, went undercover, pretended to be a farmworker, got himself arrested, all as part of his journalistic mission to expose social inequality and to challenge unjust authority,” writes theJournalist.

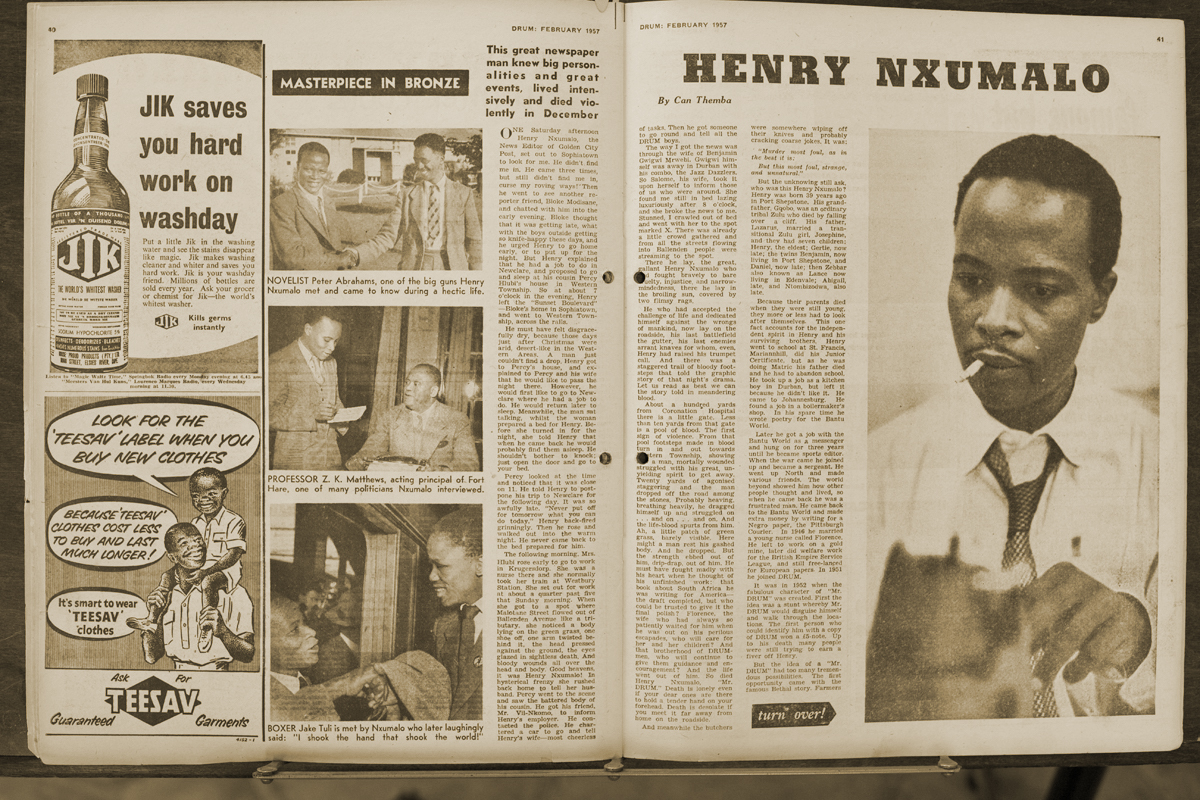

But his remarkable journalism career was short-lived as on New Year’s Eve 1957, Nxumalo was stabbed to death while investigating suspicious deaths at an abortion clinic in Sophiatown, a suburb west of Johannesburg.

He was only in his mid-30s at the time of his murder, which remains unsolved after many decades. “Why had he been killed?” and who could the killers have been, remain on the lips of many to date.

Born in 1917 in Margate, in the former Natal province, Nxumalo’s parents died when he was still at school. He began writing while he was still at school, submitting his works to various newspapers and even getting a job at the Post newspaper in Johannesburg, at a time when black journalists had few opportunities.

When World War II broke out, 22-year-old Nxumalo enlisted in the South African Army and this enabled him to visit Egypt and places like London, where he made friends with other African intellectuals and writers.

www.designindaba.com

After the war, he worked for Bantu World and became a stringer for the Pittsburgh Courier in the USA. His passion, however, was to do undercover journalism but this initially became a challenge, especially in the early post-war years where black writers and journalists were not given many opportunities.

“Mainstream newspapers in South Africa, consistent with the policies of racism and apartheid, offered few opportunities for black reporters, while black newspapers were either very small or controlled by white business interests, often featuring trivial and sensational content. Independent investigative journalism of the type that Nxumalo envisaged simply did not exist at the time,” writes South African History Online.

Then came in the Drum Magazine, established in 1951 by millionaire Jim Bailey. Becoming the premier publication targeting urban black readers, Nxumalo became the magazine’s first black writer and its assistant editor.

Emerging as the most brilliant star of the magazine, Nxumalo, whose nickname was ‘Mr Drum’, became well-known for one of his landmark exposé’s – an investigation he did on farm labor conditions in the Bethal region.

Jurgen Schadeberg, a photographer for the Drum, said: “We were doing investigations about [working] conditions in the district where there were potato farmers. Farmers had the reputation of terrorizing workers, using children as slave laborers, killing people and exploiting them. I went with him [Nxumalo] in the area. He signed up as labor in order to do the story, which is pretty tough.”

“There was really no other way to do the Bethal story’, Schadeberg said in the book A Good Looking Corpse by Mike Nicol.

“Henry had to discard his suit, dress in tattered clothes like a farm laborer and go and find work on the farm. Which he did. And then after a few days picking potatoes he escaped at night. It was a dangerous situation to run away at night: he could have been shot, killed, but there was no other way to do it.”

Interviewing more than fifty laborers while working undercover, Nxumalo “was told stories of laborers flogged to death, of others who died of cold, of repeated beatings, of farmers known as ‘Mabulala’ (the Killer) and ‘Fakefutheni’ (Hit him in the marrow),” according to Nicol.

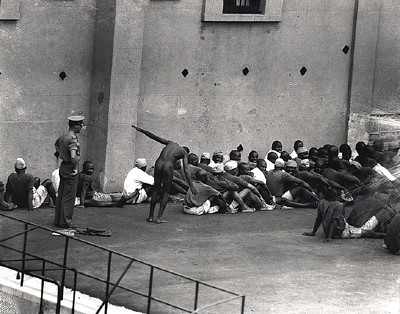

Nxumalo is also popular for another investigative work that looked into detention conditions at Johannesburg’s central prison – The Fort – in 1954.

After his release from jail in March 1954, Nxumalo wrote for Drum: “I served five days’ imprisonment at the Johannesburg Central Prison from 20 to 24 January. My crime was being found without a night pass five minutes before midnight, and I was charged under curfew regulations.”

He continued: “Thrashing time for warders was roll call and breakfast time as well as supper time. For long-term prisoners it was inside the cells at all times. Long-term prisoners thrashed more prisoners more severely and much more often than the prison officials themselves, and often in the presence of either white or black warders. All prisoners were called kaffirs at all times.”

Uproar greeted his exposé, compelling the government to pass a law that restricted anyone from reporting on conditions in South African prisons. Risking his life through investigative reports, many believed that it was Nxumalo’s bravery which gave him his name and reputation and also helped to build Drum.

But six years after helping establish Drum, Nxumalo was stabbed to death by unknown assailants while investigating an abortion racket operated by a well-known doctor.

“There was a doctor who was attached to a police station in the area, and it was known that there had been some botched abortions, some of the patients died. [Nxumalo] tried to investigate it. He went to talk to nurses,” Schadeberg said.

While walking home after meeting a colleague for drinks, the famed investigative journalist was killed.

“We tried to investigate, but police were sloppy about it. They weren’t interested,” said Schadeberg. Others wondered who the killers could have been.

“Was it the Government who wanted to silence one of their fiercest critics? Was it a passing “tsotsi” looking for a quick buck? Or was it the notorious, “Mr Big, the white abortionist”, who Nxumalo was said to be investigating at the time?” asks theJournalist.

39-year-old Nxumalo left behind a wife and three children. The Drum could not continue with his kind of journalism as the magazine and its reporters became targets of the apartheid government.

By the early 80s, the magazine had gone bankrupt, and what many do know is that it was eventually acquired by the then-pro-National Party newspaper group Naspers.

What is, however, not known is why exactly Nxumalo was killed and who the assailants could have been.

“Unfortunately, this is an all too familiar pattern in anti-press violence, where murder represents the ultimate tool of censorship and where authorities lack political will to deliver justice,” writes the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in 2012.

“I cannot hide my bitterness at all,” Can Themba, a friend of Nxumalo, was quoted in Nicol’s book.

“But, dear Henry, Mr Drum is not dead. Indeed, even while you lived others were practising the game of Mr Drum. Now we shall take over where you left off,” he said.