During the apartheid system in South Africa, a person’s racial classification determined who he could marry, where he could live, the types of jobs he could get, and so many other aspects of life.

Numerous ways such as pencil test were performed in South Africa during the apartheid regime and were used to determine racial identity, distinguishing whites from coloureds and blacks. The pencil test, for example, decreed that if an individual could hold a pencil in their hair when they shook their head, they could not be classified as White.

This was implemented under the Population Registration Act of 1950 which required that each inhabitant of South Africa be classified and registered in accordance with his or her racial characteristics as part of the system of apartheid. In that case, South Africans were divided into four groups: whites, Asians/Indians, coloureds and “natives” or blacks.

People who thought they were misclassified could go before a panel and plead their case at Race Classification Appeal Board.

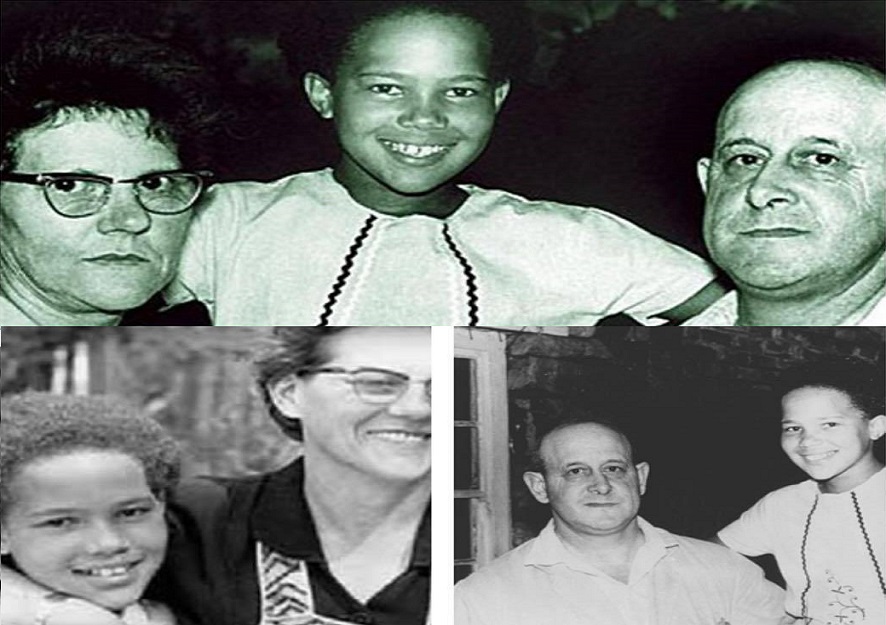

On March 10th, 1966, Sandra Laing, a 10-year-old dark-skinned Afrikaner girl was removed from her all-white school and escorted home by two police officers (yes, two of them!) due to complaints from parents of other students, based on her appearance: primarily her skin colour and the texture of her hair. Teachers and parents had fought for four years to have her kicked out.

For Sandra, the dismissal was more of a relief from white children who called her names, like “blackie” and “frizzhead”. She was subjected to racist bullying and school did nothing to stop it, instead saw her as the cause of the trouble.

Sandra was born to white parents but she displayed the physiognomy of African ancestors of earlier generations, perhaps from the 18th century or more recent. Her family treated her as white, the same as their two sons.

Her pro-apartheid parents chose to take the case to the Supreme Court but they lost, and Sandra was to remain coloured. Her father underwent a test which proved his paternity.

Sandra was later re-classified as white when the law was changed to say the child of two white parents could not belong to another racial group. Even after the tests that proved her white father was her biological father, and despite being classified as White by law, she was still ridiculed and shunned. Her only friends were the children of the black servants.

At 16 she left the “white world” for good and eloped to Swaziland with a black man who would later marry her and have two children together.

Sandra would not be allowed to keep her two children unless she was reclassified coloured. At the age of 26, she tried to get herself changed back to coloured so they could stay with her, but her father denied his consent. It took her ten years to get them back.

In 1977 a film titled In Search of Sandra Laing was released but banned from distribution in South Africa.

As apartheid entered crisis in the 1980s Sandra tried in vain to contact her family, only to learn that her father had died and her mother did not want to see her.

Sandra left her first husband who had turned a drunkard and married Johannes Motloung, with whom she had another three children after being reunited with her first two.

In 2000, a local newspaper tracked her down to learn about her years since the end of apartheid. The newspaper helped her find her mother after 27-year estrangement and they were able to reconcile just before she died at a nursing home.

The publicity also galvanised a campaign to find Sandra a house of her own in Leachville, Johannesburg.

As of 2009, her two brothers remained unwilling to see her. They blamed her for their parents’ unhappiness though she continued to hope they would someday have a change of heart.

Sandra said in an interview in 2009 that: “At first I was very angry of White people and angry of the apartheid government for [making me choose to be a different race other than my parents], but I decided that it doesn’t help to be angry. I had to learn to go on with my life and forget what happened. I was classified colored and I loved all Black people. I’ve got colored and Blacks in my family and most of my friends are Black and [that’s what race I most identify with].”

Her life experience has inspired a number of documentary and dramatic films such as Skin, as well as a book.