For the first time since he died and was mummified 3,000 years ago, the voice of an ancient Egyptian priest has been heard.

Researchers have been able to mimic the voice of a 3,000-year-old Egyptian mummy, priest Nesyamun by recreating its vocal tract using medical scanners, 3D printing, and an electronic larynx.

According to the Journal of Scientific Reports published on Thursday, the technique allowed them to produce a single sound between the vowels in ‘bed’ and ‘bad’ despite the tongue losing much of its bulk over three millennia.

Priest Nesyamun lived around the beginning of the 11th century BC under the reign of Pharaoh Rameses XI. He was a priest, incense-bearer, and scribe at the ancient Egyptian temple complex at Karnak.

Nesyamun’s mummy which is currently laying in Leeds City Museum has been under careful examination since it was unwrapped in 1824. It was later revealed that he had died whilst he was in his 50s.

Others have also suggested that he died from strangulation but reports say he had no damage to the bones around his neck.

The cause of his death was later suggested to be by an allergic reaction, possibly as a result of an insect sting to the tongue which experts attribute to the reason why the mummy had his tongue sticking.

Nesyamun’s mummy was moved prior to a bombing raid on Leeds in 1941 that destroyed the museum it had been in.

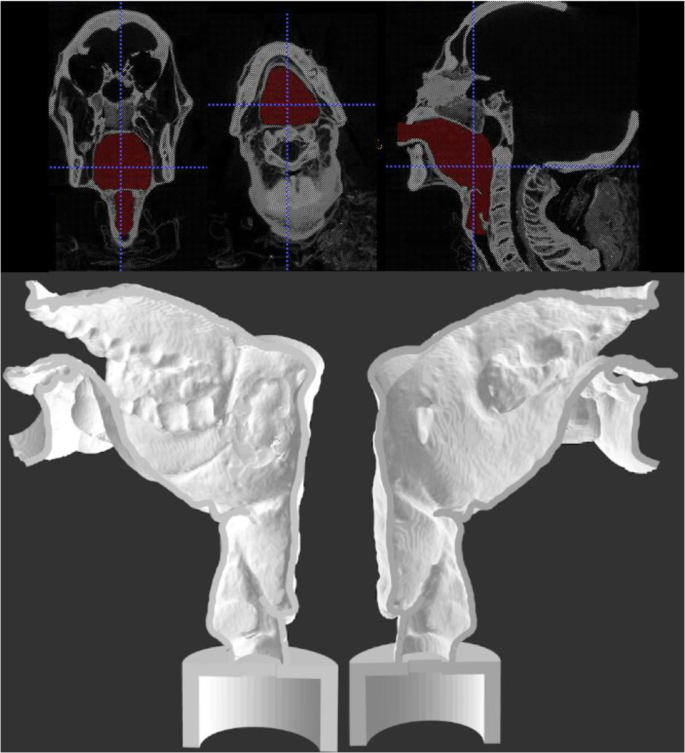

Decades later, a team of researchers has a 3D-printed reproduction of Nesyamun’s vocal tract to hear what his voice would have sounded like.

“What we have done is to create the sound of Nesyamun as he is in his sarcophagus. It is not a sound from his speech as such, as he is not actually speaking,” said the study co-author Prof David Howard, head of the department of electronic engineering at Royal Holloway, University of London.

The team revealed in the Journal that they took the mummy to Leeds General Infirmary where they carried out a series of CT scans that allowed to produce a digital reconstruction of Nesyamun’s vocal tract and reproduce it through 3D printing.

The sound is more specifically that of Nesyamun lying in his coffin after mummification, Howard said.

Study co-author, Prof Joann Fletcher of the department of archaeology at the University of York also points out that “Every Egyptian hoped that after death their soul would be able to speak, in order for them to recite the so-called ‘negative confession’ telling the gods of judgment that they had led a good life.”

“Only if the gods agreed could the deceased soul pass through into eternity if they failed the test they died a second, permanent death. Those who passed the test were termed “true of voice” – a phrase that appears in Nesyamun’s coffin inscriptions alongside his name, ” Fletcher added.

Another co-author of the study also at the University of York who is an archaeologist, Prof John Schofield said the team’s approach could offer the public a new way to engage with the past.

“It is just the sheer excitement and the extra dimension that this could bring to museum visits, for example, or site visits to Karnak,” he said.

“The idea of going to a museum and coming away having heard a voice from 3,000 years ago is the sort of thing people might well remember for a long time.

“What we’d like to try to do next is develop a computer model that will allow us to move the vocal tract around and form different vowel sounds and hopefully, ultimately words,” he said.

“This current sound is never a sound he would have made in life, but from it, we can create sounds that would have been made during his lifetime.”

Schofield thinks that the approach could also be applied to other preserved human remains.